Goat in Minnesota tests positive for H5N1 bird flu strain that’s on the WHO’s pandemic watchlist in first ever US case – as experts call it a ‘worrisome development’

A goat in Minnesota has tested positive for bird flu, the first case of bird flu in domestic animals in US history.

The baby goat, which tested positive for the highly pathogenic bird flu strain H5N1, the bird flu strain that has been spreading since 2022, came from a farm in Stevens County in the western part of the state.

Officials suspect the goat contracted the flu from the infected bird because the animals shared the same space and had access to a shared water source.

Dr. Thomas Moore, an infectious disease physician at the University of Kansas, says this marks a “worrisome development” because it shows the virus is getting closer to infecting other mammals and even humans.

It is rare for mammals to get bird flu because they have fewer receptors in their upper respiratory tract to which the virus binds.

The baby goat, which tested positive for the highly pathogenic bird flu strain H5N1, the bird flu strain that has been spreading since 2022, came from a farm in Stevens County in the western part of the state.

Officials suspect the goat contracted the flu from the infected bird because the animals shared the same space and had access to a shared water source (stock image)

All animals have been quarantined and there is an “extremely low” risk to the public, with only those who have been in direct contact with the animals at risk, the Minnesota Board of Animal Health said.

Although there appears to be no mutation this time, experts told DailyMail.com that the longer the virus remains undetected in mammals, the more likely it is to mutate.

The farm had already suffered an outbreak of H5N1 in poultry in February, and the birds had been quarantined in an attempt to stop the spread.

Health officials are still investigating how the virus was transmitted and the board said it has quarantined all other species on the farm.

‘Fortunately, research to date has shown that mammals appear to be dead-end hosts, meaning they are unlikely to further spread HPAI.’

Animals with weakened immune systems, such as baby goats in this case, are generally at greater risk of contracting diseases.

But Dr. Moore told DailyMail.com it was a reminder that bird flu could acquire a mutation at any time that makes it transmissible to humans.

He said: ‘It is clearly a worrying development. Because you don’t know where it ends? …The virus is constantly replicating and we don’t really know where it will end up.

“I think it’s reasonable to assume this is the only goat that is infected. Especially if you have a documented infection and poultry in the area.”

He added: ‘The point is you’re a bit concerned about whether it is transmissible to wild birds in the area, which can then transport it. You can do as many quarantines as you want for goats and domestic poultry, but if you think wild birds are acting as a vector, then it can spread widely.”

Dr. Brian Hoefs, state veterinarian, said: ‘This finding is significant because, while spring migration certainly represents a higher risk period for poultry transmission, it highlights the possibility of the virus infecting other animals on multi-species farms.’

No one has become ill after contact with mammals infected with bird flu.

In August 2023, ttwo people inside Michigan was diagnosed with pigs flu after being exposed to infected pigs at provincial fairs.

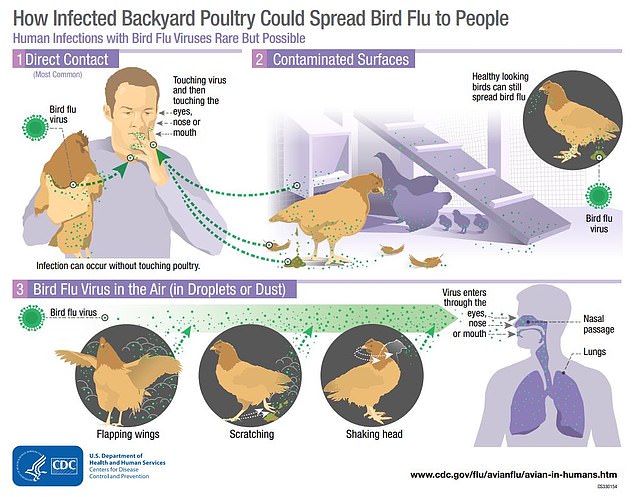

Like all flu, the virus is spread primarily through airborne droplets that are inhaled or land in a person’s mouth, eyes, or nose.

The current outbreak of bird flu has been raging for almost two years and is for the first time affecting every corner of the world, including Antarctica.

Experts have warned that increasing cases in mammals could lead to a recombination event – when two viruses, such as bird flu and seasonal flu, swap genetic material to create a new hybrid.

A similar process is believed to have caused the 2009 global swine flu crisis, which infected millions of people across the planet.

For decades, scientists have warned that bird flu is the most likely candidate for causing the next pandemic.

This could cause a deadly bird flu to merge with a transmissible seasonal flu.

In Britain, a December report found that four samples from the infected otters and foxes “demonstrate the presence of a mutation associated with potential benefits for infection in mammals.”

The UKHSA warned that the ‘rapid and consistent acquisition of the mutation in mammals may imply that this virus has a propensity to cause zoonotic infections’ – meaning it could potentially spread to humans.

Yuko Sato, a veterinarian and poultry extension diagnostician at Iowa State University, told DailyMail.com that there appears to be no mutation between the virus received from the goat and the virus received from the chicken.

“Fortunately, it looks like it’s just a horizontal spread,” she said.

But she added: ‘The biggest risk is probably that the virus is present unknowingly in different groups of animals.

‘The longer the virus is around, the greater its ability to mutate. Once something is wrong, I think it’s great that (Minnesota farmers) got it diagnosed and investigated very quickly because the longer it festers, the more problems there are going to be.”

As to whether this increases the risk of human spillover, she said: “I don’t know yet. But this virus seems more likely to have that potential than the previous virus in 2015.”

The last case of bird flu in a commercial flock of birds in America was in June 2015.

An outbreak of bird flu occurred between December 2014 and June 2015, with more than 200 cases of bird flu in both backyard poultry and wild birds.

Bird flu led to the slaughter of five million birds in the US in 2023 in an attempt to prevent an outbreak.

Last year, Dr Sylvie Briand, WHO Director for Epidemic and Pandemic Preparedness and Prevention, said: ‘The global H5N1 situation is worrying given the widespread spread of the virus in birds around the world and increasing reports of cases in mammals , including people. ‘

H5N1 was first detected in chickens in Scotland in 1959, and again in China and Hong Kong in 1996. It was first detected in humans in 1997.

Human-to-human transmission of H5N1 is incredibly rare, but not impossible. In 1997, officials confirmed 18 H5N1 cases in Hong Kong, some of which were acquired through human-to-human transmission. However, the outbreak remained relatively small. And it did not lead to a large-scale problem, either locally or globally.

This recent outbreak has caused particular concern. More than 15 million domestic birds and countless wild animals have been affected by the virus.

Nothing can be done to prevent the spread among wild birds, but officials are doing their best to keep domesticated populations away from them. In Britain, all farmed chickens must now be kept indoors.