Giving children as young as SIX diet pills like Ozempic could tackle the spiral of diabetes under 40, says top expert

Children aged six and over should be given weekly weight loss shots to tackle childhood obesity and help prevent the type 2 diabetes crisis sweeping Britain, a top expert says.

It comes after Diabetes UK revealed that poor diet has caused a 39 per cent spike in the condition among under-40s over the past seven years.

Giving obese children semaglutide – also known as Ozempic and Wegovy – could reduce their chances of suffering from the condition by as much as 90 percent, studies have found.

The drug, administered by self-injection once a week, regulates blood sugar levels and helps patients lose weight by suppressing appetite.

Leading obesity and diabetes researcher Professor Carel Le Roux said: ‘It is definitely a good option to treat children with the disease of obesity from six years of age.

Research has shown that adults taking semaglutide can lose enough weight around their organs to reduce the risk of diabetes by 90 percent, or even put existing cases into remission.

And a ‘stunning’ international study involving children as young as 12 showed the same results also occurred in younger patients.

If dietary interventions have failed, children should be offered treatment with semaglutide, experts say

‘The goal is health gain, not weight loss. If you have a six-year-old who has apnea and mobility problems and you are treating him to improve his health, this is the right thing to do.

“If they don’t have complications of obesity, that may not be the case.”

Danish pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk, which makes the popular semaglutide jabs under the brand names Ozempic and Wegovy, has already announced a global trial in children, including in Britain.

Studies have shown that adults taking semaglutide can lose enough weight to reduce their risk of diabetes by 90 percent, or even put existing cases into remission.

And a ‘stunning’ international study involving children as young as 12 showed the same results also occurred in younger patients.

Professor Le Roux said giving the drug to children could help reduce the number of cases of diabetes among young people.

‘I wish everyone in the world would run more and eat healthier. But running around and eating healthy is not a solution to the disease of obesity, and we need to be clear about that.”

‘We have rare conditions such as familial hypercholesterolemia, where children are born with high cholesterol and have a heart attack in their 20s or 30s.

‘We can determine the risk almost from birth, so the question is when you should start taking (cholesterol-lowering) medicines to reduce the risk.

‘We have to look at this the same way. We place obesity in the same box as all other childhood diseases, it is no different.

‘We treat it like any other disease, so we think about how we can make patients healthier, and when the benefits of treatment outweigh the risks. That’s what we need to do: forget about the weight and focus on health.”

He added that there is evidence that obesity relapses once patients stop taking semaglutide, so they should be prepared to continue taking it for the rest of their lives.

But Professor Barbara McGowan, a diabetes expert based at King’s College London, said she would be reluctant to give semaglutide to children before all other options had been exhausted.

‘Just giving children pharmacotherapy is not the solution. But for some children it can be part of an intervention.

‘We have an obesity epidemic, and obesity and type 2 diabetes go hand in hand.

‘We need much broader changes at a system level. We need to change the environment – to tackle the food industry, advertising, fast food restaurants, portion sizes, and so on. It is a very complex situation.

‘We have to provide education at school. We need to educate healthcare professionals, but also parents and the rest of the population.

“For the kids who are really struggling, where all lifestyle interventions have been exhausted, semaglutide could be a new weapon in the armory to help treat them.

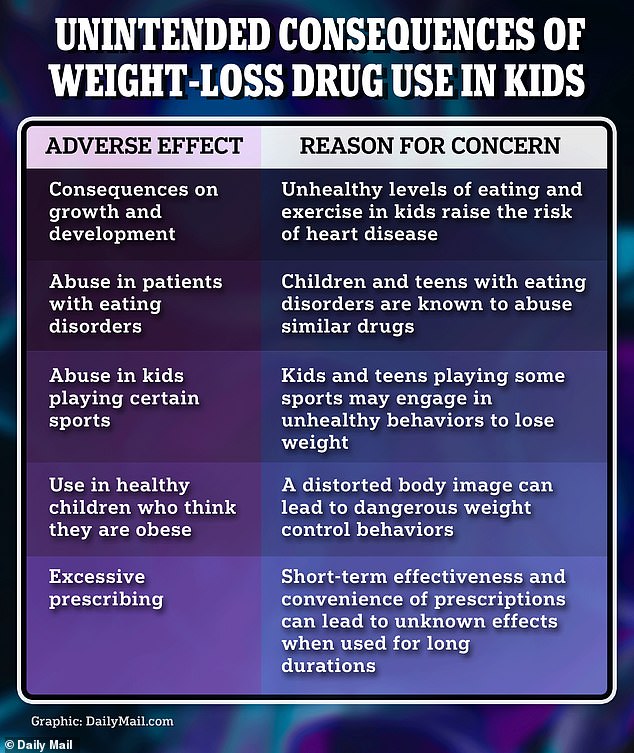

Researchers outlined several unintended harmful consequences that could occur in children taking weight-loss medications

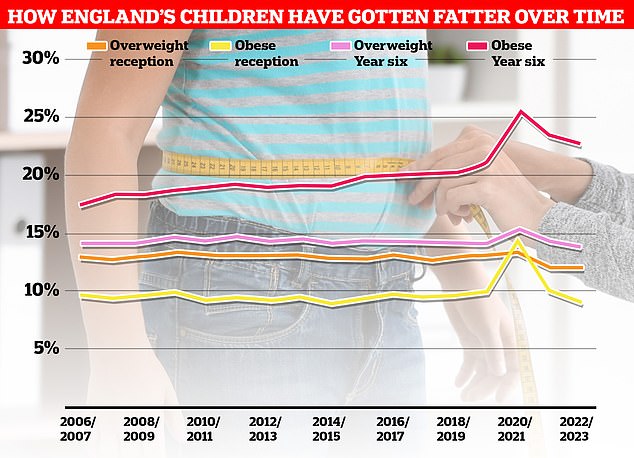

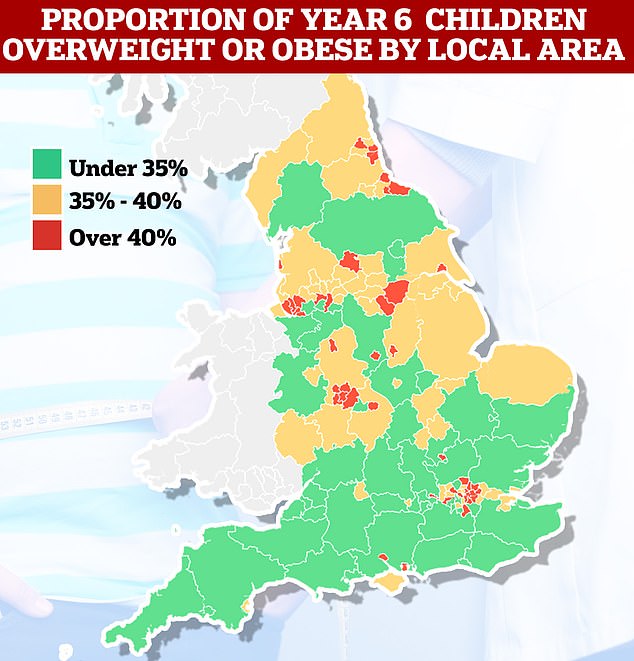

More than a million children had their height and weight measured as part of the National Child Measurement Program (NCMP). Nationally, the rate among children in the sixth form is well over a third, despite falling slightly since the start of Covid

Among sixth grade students, national obesity decreased from 23.4 percent in 2021/2022 to 22.7 percent. Meanwhile, the proportion of children considered overweight or obese also fell from 37.8 percent to 36.6 percent. Both measures are above pre-pandemic levels

‘But it must be part of a multifaceted approach. It’s not a panacea. But there will be kids who are struggling, and this will hopefully help.

‘These medications help improve diabetes, but also act on the brain centers that influence appetite. You can eliminate the cravings and help address the diet so they are more likely to eat healthy foods.

‘Early intervention can help prevent many of the complications that cost a lot of money when it comes to treating type 2 diabetes.’

The NHS said current semaglutide drugs such as Wegovy are not licensed for children under 12, and that the government’s drug rationing agency, NICE, does not currently provide funding for people under 17.

Technically, children in Britain can still receive semaglutide, as doctors can prescribe it to children because the drug is already approved for use in adults, a standard of practice for numerous medications.

NHS doctors can in theory give it to children because the drug is already approved for use in adults, a standard of practice for numerous drugs.

The US and EU have already approved the drug for use in obese children aged 12 and over, under limited circumstances.

However, the NHS medicines watchdog, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), said it could not make a recommendation on Wegovy in children in June, citing a lack of evidence from Novo Nordisk.

The latest data on childhood obesity in England shows that one in ten children are overweight by the time they start primary school, rising to around one in four by the sixth year.

Obesity also takes a huge financial toll in Britain, with consequent health consequences in terms of lost working years, healthcare costs and the price of NHS treatments, costing the economy an estimated £100 billion a year.

Experts have pointed to a lack of exercise and a poor diet high in ultra-processed foods as major causes of Britain’s childhood obesity epidemic.