Give children as young as SIX diet shots like Ozempic, experts urge, as trial proves success in children

Research has shown that weight loss injections could be prescribed to children as young as six years old after they were shown to reduce obesity and other health problems.

In those who took liraglutide for just over a year, BMI fell by more than seven percent and blood pressure and blood sugar levels decreased.

Experts say the discovery could one day turn the tide and tackle America’s childhood obesity crisis, allowing children to lead “healthier, more productive lives.”

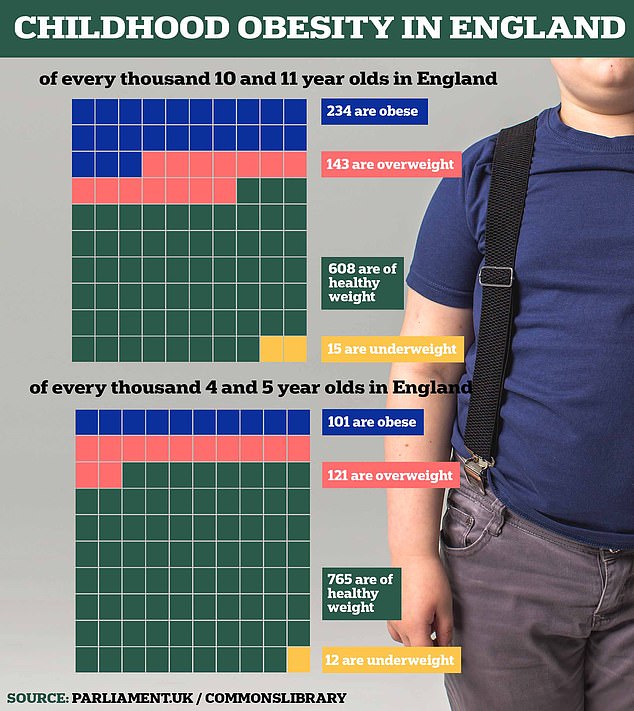

More than one in five children in England are overweight when they start school, rising to one in three by the time they reach secondary school.

This makes them more likely to develop a number of chronic conditions in childhood and later in life, such as heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes and certain types of cancer.

Research has shown that diet pills reduce the BMI of children aged six and over by more than seven percent.

Injections such as Ozempic, Mounjaro and Wegovy have been linked to a growing list of health benefits for adults, with a study earlier this year finding they cut the risk of heart problems by a fifth.

Last year, a study among adolescents aged 12 to 18 found that administering vaccinations for 16 months halved obesity rates, in combination with lifestyle advice.

In the study with the youngest patient to date, the drug or a placebo was given to 82 children aged six to 12, with an average BMI of 31, which puts them in the obese category.

About 56 children were given a daily injection of 3 mg or the maximum tolerated dose for 56 weeks and 26 were given a dummy drug. At the same time, they were encouraged to eat healthily and exercise.

At the end of the study, the average BMI was 5.8 percent lower in those taking liraglutide and increased by 1.6 percent in those taking a placebo – a difference of 7.4 percent.

Although it is normal for children to gain weight as they get older, the average weight gain was 1.6 percent when given liraglutide, compared with 10 percent when given the dummy shot.

Nearly half of the children (46 percent) who took the drug, known by the brand name Saxenda, had a 5 percent lower BMI.

According to the latest official data, about one-fifth of children in the sixth grade are obese

By comparison, only eight percent of children who received a placebo had the same number, according to findings published in the New England Journal of Medicine and presented at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes Obesity in Madrid.

According to professor Claudia Fox of the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, the drug can help where lifestyle changes don’t work.

She said: ‘The results of this study are promising for children living with obesity.

Until now, children have had virtually no options for treating obesity, being told to “try harder” with diet and exercise.

‘Now that there may be a drug that addresses the underlying physiology of obesity, there is hope that children with obesity can lead healthier, more productive lives.’

According to the study’s lead researcher, a five percent reduction in children’s BMI has previously been linked to an improvement in certain health problems associated with obesity.

She added: ‘In our study, diastolic blood pressure and haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a measure of blood sugar levels, improved more in children given liraglutide than in children given placebo.’

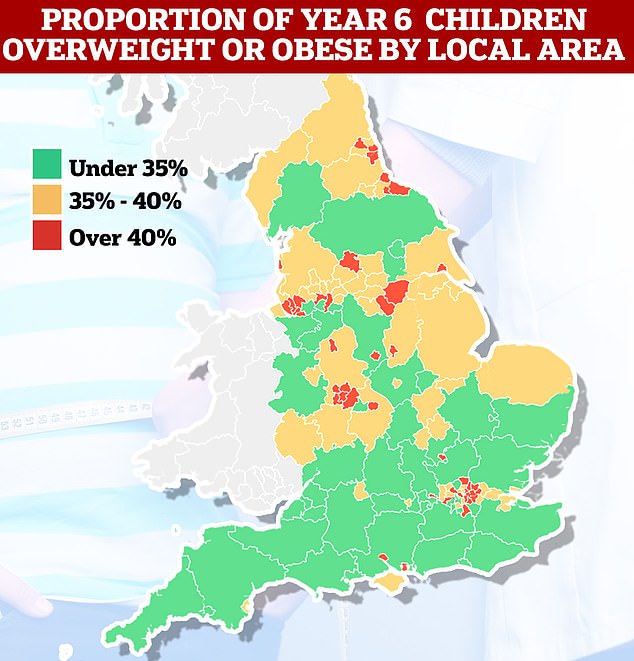

Among Year 6 pupils, national obesity fell from 23.4 per cent in 2021/22 to 22.7 per cent. Meanwhile, the percentage of children considered overweight or obese also fell from 37.8 per cent to 36.6 per cent. Both measures are above pre-pandemic levels.

Obesity rates are skyrocketing in children, with one in ten now considered obese in their first year of school. Data for 2021/22

The findings are likely to add to growing calls for drugs such as liraglutide, which is currently prescribed by the NHS to adults with a BMI of over 30, to also be prescribed to obese children.

However, side effects such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea were common and occurred in eight out of ten children receiving liraglutide, half of whom were in the placebo group.

More serious reactions occurred in 12.5 percent of people who received the drug, compared with 7.7 percent in the control group. As a result, one in 10 people who received the vaccine stopped before the end of the trial.

Dr Nerys Astbury, senior lecturer in nutrition and obesity at the University of Oxford, said of the findings: ‘These promising findings raise the possibility that safe and effective drugs may soon be available to treat obesity in children and adolescents.

‘Because treating children and adolescents with obesity may have long-term health benefits, we should consider their value in reducing the risk of obesity-related conditions and improving long-term health, even though these drugs are currently expensive.