Girls who are overweight in their youth are more likely to experience early puberty, genetic research shows

Genetic research has shown that girls who are overweight in childhood have a greater risk of early puberty.

In the largest study of its kind to date, a team from the University of Cambridge studied the DNA of around 800,000 women from around the world.

They discovered more than a thousand variants – small changes in the DNA – that influence the age at which girls get their first period.

Just under half of these variants affected puberty by increasing weight gain in early childhood.

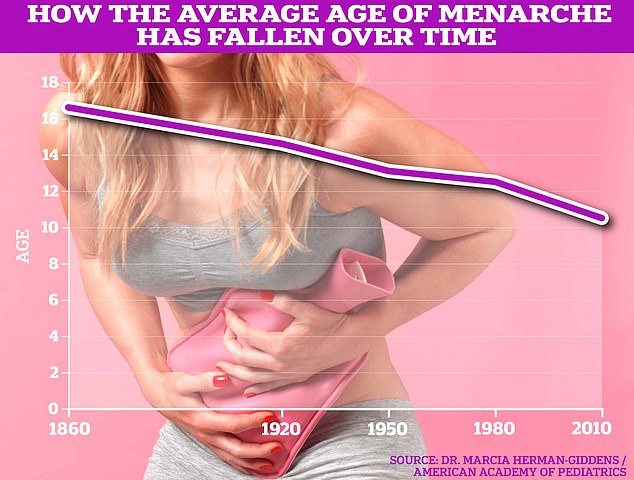

The age at which girls start puberty and get their period is normally between the ages of 10 and 15, although this has become increasingly earlier in recent decades.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge discovered more than a thousand genetic variants that influence the age at which girls get their first period. Just under half of these variants affected puberty by increasing weight gain in early childhood

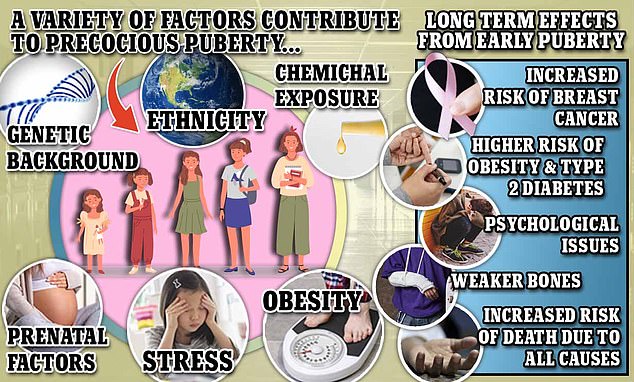

The increased risk starts at menarche in people under the age of 13 and increases the younger they are. Experts think this may be due to higher levels of estrogen, which they are exposed to for longer periods of time

Doctors have been unable to identify a single or even a handful of causes for precocious puberty, although experts told DailyMail.com that some underlying factors include obesity, stress and genetics

Early puberty is associated with an increased risk of a number of diseases later in life, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and certain types of cancer.

Previous studies have shown that obesity is associated with early puberty in both boys and girls.

Professor John Perry, one of the study’s authors, said: ‘Many of the genes we found influence early puberty by initially accelerating weight gain in babies and young children.

‘This could lead to potentially serious health problems later in life, as earlier puberty leads to higher rates of overweight and obesity in adulthood.’

The researchers also generated a genetic score that predicted whether a girl was likely to enter puberty very early or very late.

Girls with the highest 1 percent of this genetic score were eleven times more likely to have extremely delayed puberty, after the age of 15.

In contrast, girls with the lowest genetic score of 1 percent were 14 times more likely to have extremely early puberty before age 10.

Senior author Professor Ken Ong said: ‘In the future, we may be able to use these genetic scores in the clinic to identify girls whose puberty will come very early or very late.

‘The NHS is already doing whole genome testing at birth, and this would give us the genetic information we need to make this possible.

‘Children in the NHS who are in very early puberty – at the age of seven or eight – are offered puberty blockers to delay puberty.

“But puberty is a continuum, and if they miss this threshold, we have nothing to offer at this point.

“We need other interventions, whether that’s oral medications or behavioral approaches, to help. This could be important for their health as they grow up.”

Lead researcher Dr. Katherine Kentistou added: ‘The novel mechanisms we describe could provide the basis for interventions for individuals at risk of early puberty and obesity.’

Previous work by the team showed that a receptor in the brain, known as MC3R, senses the body’s nutritional status and regulates the timing of puberty and growth rate in children.

Other genes identified appeared to work in the brain to control the release of reproductive hormones.

The findings are published in the journal Nature Genetics.