Meet the ‘gilded lady’: Scientists reconstruct the face of a mysterious mummy who lived in Egypt 1,500 years ago and was known for her ‘golden headdress’

A mysterious mummy, known only as the Gilded Lady for her golden headdress, has been seen for the first time after scientists reconstructed her face.

The woman lived in Roman-occupied Egypt and died at the age of 40, possibly from tuberculosis. Her mummy contained no hieroglyphs that could reveal her name.

To protect her remains, she was never unwrapped, but in 2011 she was given her first CT scan, revealing new details about the body.

Now, more than 1,500 years after her death, her true face has been revealed, revealing her ‘fine’ features as they were during her lifetime.

According to Cicero Moraes, lead author of the new study, the reconstruction is possible in part due to the careful preservation of the mummy.

A mysterious mummy known only as the Gilded Lady for her golden headdress has been seen for the first time after scientists reconstructed her face

The woman lived in Roman-occupied Egypt and died at the age of 40, possibly from tuberculosis, and her mummy bore no hieroglyphs to reveal her name

He said: ‘The structure is very well preserved, in its original state of discovery, without the mummy being unpacked.

‘What is striking is the presence of short, curly hair, which can be seen on the tomography reconstruction.’

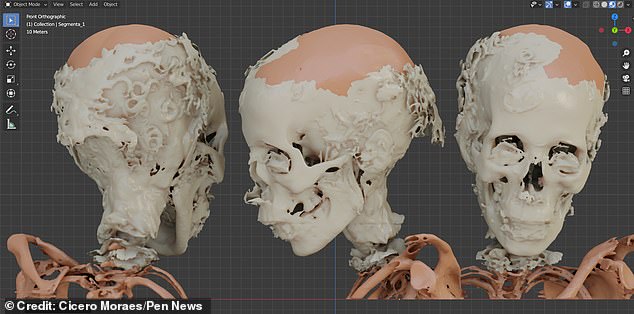

He continues: ‘Initially we reconstructed the skull based on the computed tomography and later we adjusted the position of the jaw.

‘The skull allows us to design structures such as the nose, ears, eye position, lip boundaries and others, using data measured in tomography scans of living people.

‘In addition, we use measurements performed using ultrasound, also in living people, to determine the thickness of the soft tissue in different parts of the skull.’

Because she originates from Roman-occupied Egypt, tissue thickness data from modern European women aged 40 to 49 years were used.

The resulting face was merged with another face created using a process called anatomical deformation.

Her true face has been revealed more than 1,500 years after her death, revealing her ‘fine’ features as they were during her lifetime

The team created two versions of the face: an objective one, with eyes closed, and a grayscale one to avoid making judgments about skin color

Mr Moraes said: ‘Here we adapt the face and skull of a virtual donor to fit the parameters of the gilded lady, resulting in a structurally compatible face.

‘Finally, we compare all the data and interpolate the projections to create the final face.’

The team created two versions of the face: one objective, with eyes closed, and one in grayscale, so as not to make any statements about skin color.

The other adds more artistic elements and breathes life into the recreation with color and hairstyle.

In both cases, the peculiarity of the preserved short curly hair was enhanced, revealing another aspect of the living woman’s appearance.

Cicero said: ‘It is a delicate, youthful-looking face.

“She reminds me of my mother-in-law in some ways! During the trial I showed it to some family members and they all agreed.”

CT scans also revealed that the living woman had a slight overbite, and clumps of resin were also found, likely inserted during mummification to improve the smell.

They were aided by the unusual preservation of short curly hair, which revealed another aspect of the living woman’s appearance

A CT scan also revealed that the living woman had a slight overbite, as well as lumps of resin that were likely inserted during mummification to improve the odor.

Cicero’s co-author, archaeologist Michael Habicht of Flinders University in Australia, said the burial “is indicative of a middle-class person”.

The remains are now kept by the Field Museum in Chicago, USA.

The multinational team behind the reconstruction is active on three continents.

Authors include Elena Varotto, also of Flinders University, Francesco Galassi of the University of Lodz in Poland, Veronica Papa of the University of Naples in Italy and Thiago Beaini of the University of Uberlândia in Brazil.

They published their study in Anthropologie – International Journal of Human Diversity and Evolution.