Giant salamander-like monster with huge teeth and a head shaped ‘like a toilet seat’ roamed Africa’s swamps 40 million years before the dinosaurs, scientists say

- Gaiasia jennyae lived 300 million years ago in an area in present-day Namibia

- Researchers believe it used its toilet seat-shaped head to grab large prey

Forty million years before dinosaurs walked the Earth, a much stranger monster stood at the top of the food chain.

Scientists have discovered the fossil remains of a gigantic, two-metre-long salamander-like monster with an enormous ‘head shaped like a toilet seat’.

This fearsome creature was named Gaiasia jennyae after the Gai Ash formation in Namibia where it was found. It is said to have hung out in swamps and lakes, eating anything that came near it.

Paleontologists believe that Gaiasia, with a skull over two feet long and a set of impressive interlocking canines, was a ferocious predator.

Co-lead author Dr. Jason Pardo of the Field Museum in Chicago said: ‘It has a large, flat head shaped like a toilet seat, which allows it to open its mouth and suck in prey.’

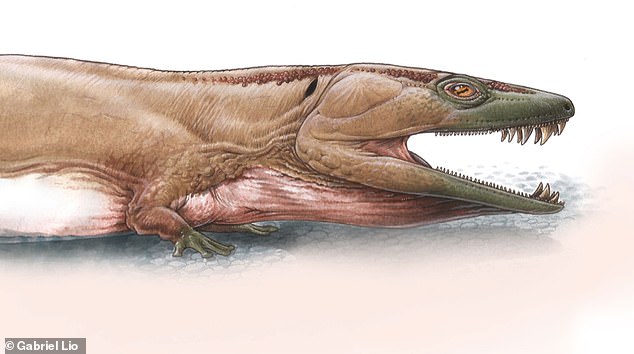

Scientists have discovered a terrifying prehistoric predator with an enormous ‘toilet seat-shaped head’ (Photo: Artist’s impression)

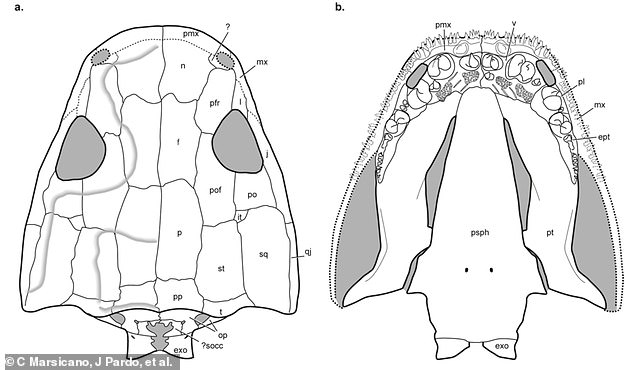

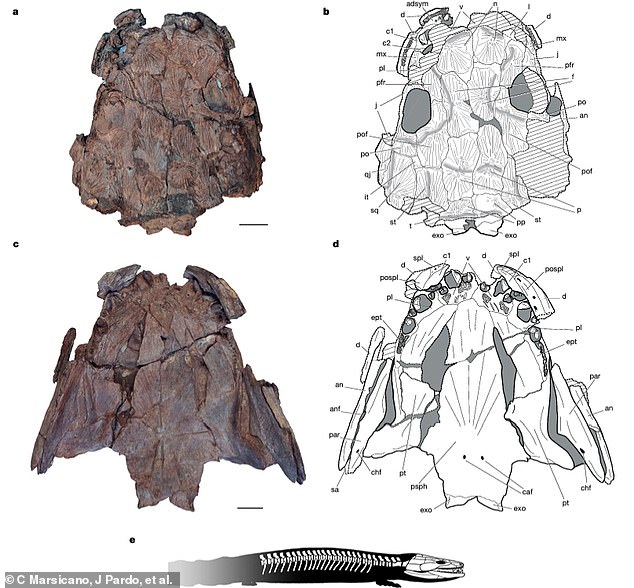

One of the specimens was so well preserved that researchers were able to find an articulated skull and spine hidden in the rock

Although Namibia now lies just north of South Africa, 300 million years ago it was much further south – close to the northernmost point of Antarctica.

At that time, the Ice Age was ending and the areas closer to the equator were drying out and becoming forested.

But in the warmer regions near the poles there were still swamps and lakes where this strange new species could establish itself.

Dr. Pardo and his co-author Claudia Marsicano of the University of Buenos Aires discovered the fossil remains of four creatures in a rock formation that is 280 million years old.

Gaiasia was considerably larger than a human – well over six feet – and had a massive skull and enormous tusks. She would have been a fearsome but slow ambush hunter.

Dr. Marsicano says, “When we found this huge specimen just lying on the outcrop like a giant concretion, it was really shocking.

“I knew just by seeing it that it was something completely different. We were all very excited.”

This creature gets its name from the Gai-as formation in Namibia, where it was found in a rock face that is 280 million years old

Researchers discovered four well-preserved specimens of Gaiasia jennyae in a region of present-day Namibia

The researchers believe Gaisia (pictured) was a fearsome, if slow, ambush predator that lurked at the bottom of lakes and swamps

One of the specimens was particularly well preserved. It had a movable head and spine that revealed a very unusual feature.

The skull of Gaiasia displayed a highly unusual set of interlocking large canines that created a unique bite for early tetrapods – the four-legged vertebrates that evolved from lobe-finned fish and gave rise to amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals.

Doctor Pardo says: ‘He has enormous canines, the entire front of his mouth is made up of gigantic teeth’

This unusual jaw structure allowed this predator to grasp and hold large prey in the prehistoric swamps of Namibia.

These traits made it one of the most important predators in the prehistoric ecosystem.

Researchers were surprised to find that the ancient animal had a full set of interlocking canines, which was highly unusual for creatures from this time period

Gaisia is an evolutionary remnant of species that went extinct 40 million years ago, but researchers believe it would have been one of the most important predators in its ecosystem.

The earliest known dinosaurs appeared during the Triassic Period, about 250 to 200 million years ago, but Gaiasia was 40 million years older.

Dr. Pardo says: ‘There are other, archaic animals that were alive 300 million years ago, but they were rare, small and did their own thing.

‘Gaisia is big and there are many of them. It seems to be the most important predator in the ecosystem.’

The species is further detailed in a new study published today in Nature.