Generation Sicknote: How an obsession with mental health issues among 18 to 30-year-olds is setting up an entire generation, as research by PROFESSOR MATT GOODWIN shows

Britain is in the grip of an escalating crisis. Yet very few people talk about it. Since the pandemic and the disastrous lockdowns that resulted, there has been an alarming trend among the over-18s and 30s, an age group increasingly in the grip of laziness, despair and dependence on the welfare state.

Currently, approximately 481,000 young people between the ages of 16 and 24 are unemployed. A remarkable 280,000 young people – roughly the population of Milton Keynes – are now dependent on some form of unemployment benefit, 50,000 more than before the pandemic and almost double the corresponding figure a decade ago.

Many readers will find these figures astonishing, not least because our leaders – in an effort to secure a workforce – have allowed net migration into the country to rise to more than 700,000 in one year, even as young Britons stay at home hanging around.

To help fill the nearly one million vacancies, the Ministry of Finance called in January for even more immigration, much of which consists of low-skilled, low-paid and non-selective migration from outside Europe.

Why can’t British youth meet the country’s labor needs?

What’s holding them back? The answer lies in the two words we now hear every day: ‘mental health’. According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), a record 2.8 million Britons are not working due to ‘long-term illness’, with a staggering 560,000 of them aged between 16 and 34.

In a report analyzing ONS figures, charity The Health Foundation says the proportion of people not working due to mental health problems has almost doubled in 11 years, from over six per cent in 2012 to 12.7 per cent in 2023.

In the absence of work, Personal Independence Payments (PIPs) are a financial lifeline for people suffering from physical or mental illness.

Most dependent applicants can receive up to £691 every four weeks, on top of other financial support they may receive, such as housing benefit and income support.

Last year, one in three new PIP claims related to anxiety, social anxiety, depression and/or stress. The increase was fastest among young people under 25 years of age.

The unbridled growth of the therapeutic state has also fostered a ‘culture of victimhood’

As one analyst, Sam Ashworth-Hayes, recently noted, “The numbers are truly breathtaking. Personal Independence Payments, previously known as the Disability Living Allowance, currently cost the government around £22 billion a year, with around 38 per cent of this expenditure going on issues related to mental health problems.”

Until recently, many of these mental health benefits did not have work requirements, meaning that people claiming some kind of mental health condition did not have to prove that they were looking for work.

After interviewing more than a thousand unemployed young Britons exclusively for the Post, I can reveal for the first time the severity of this unfolding crisis.

The results, collected by my company People Polling, paint a bleak picture of Britain’s crisis of inaction and how, in my view, we are setting up an entire generation to fail.

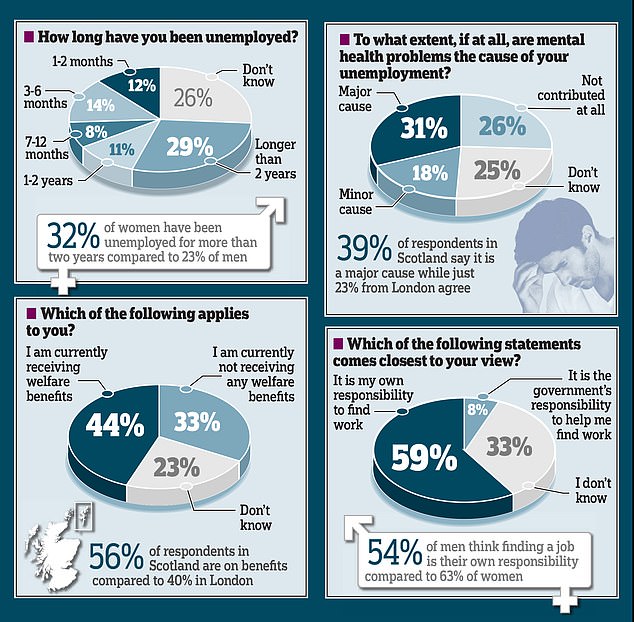

Of the unemployed young people aged 18 to 30 in our sample, about 40 percent said they had been out of work for a year or more.

And 44 percent relied on social services to survive. How that adds to their sense of purpose and meaning, and the dignity of their lives, I cannot fathom.

Some of the young Brits surveyed were carers, students or full-time parents. But a truly shocking 49 percent of respondents, almost half, pointed to “mental health issues” as the driving factor behind their unemployment.

No wonder they’ve been nicknamed ‘Generation Sicknote’: a group of young Brits whose instinctive reflex is to prioritize their mental wellbeing over getting on with life.

When we asked these young Brits to say in their own words why they’re not working, some of the answers were:

- ‘I am unemployed because of my psychological problems.’

- ‘I stopped working when the Covid-19 pandemic broke out and have since had great fear of having to work somewhere else again.’

- ‘I have difficulty with interviews because of my fear’

- ‘I have depression, anxiety and ADHD. Enough said.’

- ‘My job was having a negative effect on my mental health, so I quit.’

- ‘I just don’t feel safe when I’m around people, it makes me uncomfortable.’

I got a glimpse of this mentality during and after the lockdowns, when I noticed that many of the “Gen Z” students (born between 1997 and 2012) I taught in college became strangely withdrawn and anxious.

Having had almost no sustained contact with the rest of the world, many turned inward, away from society at large.

But can this all be attributed to the pandemic? I’m not convinced.

It’s clear that if young people are really struggling with serious mental health issues, they need support.

But it increasingly appears that the definition of ‘mental health problems’ is broadening, while we are failing to confront a much larger cultural problem.

The blunt reality is that while Chancellor Jeremy Hunt was right to recently announce a new ‘back to work’ scheme to encourage people on benefits to get back to work, it won’t make much of a difference. Why? Because we are too quick to provide support and welfare for all kinds of mental health problems – and this in turn increases the role of the state and convinces more and more young people that it is perfectly acceptable to depend on the government for their problems. everything.

And this has been going on for a long time. In the 1970s and 1980s, there were warnings about the dangerous rise of the “therapeutic state” — about the way governments were moving away from forcing people to commit to ongoing mental health treatments and serving the ” emotional well-being’ of people.

Since then, therapy, counseling and mental health have become key functions of the state, while our institutions – from universities to schools – are now falling over themselves to provide ’emotional security’ and cater to the every whim and wish of a visibly vulnerable, insecure person. and anxious younger generation.

As academics Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff noted in their recent book, The Coddling Of The American Mind, many universities today routinely emphasize the need for students to have “safe spaces,” provide “trigger warnings” for controversial topics, and “not hire therapists fast enough to meet demand.”

This is reflected in our exclusive poll, which remarkably shows that only just over half of unemployed young people think it is their responsibility to find work.

And that’s not all.

The unbridled growth of the therapeutic state has also fostered a ‘culture of victimhood’.

In Western societies, young people are actively encouraged by the state, their schools and other institutions to see themselves as victims – of mental health problems, ‘racism’, ‘sexism’ and ‘white privilege’.

As a study by American sociologists Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning shows, countries like Britain once fostered cultures that prioritized courage and honor, but today they practice a much weaker and more narcissistic culture of victimhood.

In this context, Campbell and Manning say, struggling with mental health can give young people “a kind of moral status based on suffering and neediness.”

You see this all over social media, where you don’t have to look far to find visibly lost, aimless and confused young people talking about their ‘mental health problems’, rather than, for example, what they have achieved at work or how they have done that. contribute to broader society.

The strain this culture is putting on public finances is bad enough – the state is expected to hand out £50 billion in disability and mental health benefits by the end of this decade – but its effect on a person’s pride and careers generation of people will be corrosive.

It appears that this crisis will get much worse unless we radically change course. A key reason why the UK economy is still underperforming other advanced countries is precisely because of the lack of labor, with young people becoming a big part of this story.

So if we are serious about getting Britain moving again, the government’s priority now must be to get these young Brits back into work, give them a sense of purpose and meaning in their lives and the therapeutic state to turn back.

Because if we don’t, Britain risks becoming even sicker than these young people say they are.