Millions crippled with debt, our elderly dying destitute – it’s not a dystopian fiction, it’s Australia under Anthony Albanese: STEPHEN JOHNSON reveals the facts we can’t ignore any longer

Buying a house to live in and making lifelong friends with neighbors has long been seen as a rite of passage in Australia.

For generations, owning a home with a backyard has given families stability, maintained close ties to the community, and given young couples something to work toward.

There is also room to grow vegetables, exercise in the garden or read a book under a tree.

Not to mention the financial freedom of being a landlord and the feeling of having a stake in your suburb – feeling like a valued member of society rewarded for hard work.

But what has long been considered the great Australian dream is now increasingly becoming just that: a utopia.

This will undoubtedly cause more social problems, worsen social tensions, leave millions in debt and the elderly struggling to survive, and even lead to unrest on the streets.

Younger Australians Real are worse off now than they were during the Great Depression – at least when it comes to housing affordability – with ever-increasing immigration levels reaching record highs under Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, robbing younger generations of an economic future.

And it means that many of you reading this will never own a home and will face the prospect of lifelong financial insecurity through no fault of your own.

Owning a home with a backyard has provided stability and close ties to the community for generations (pictured is a stock photo of an Australian backyard)

AMP chief economist Shane Oliver, who compared house prices in the capital with wages from the 1920s, tells me that many younger people are likely to remain renters for life, while housing affordability is the worst it has ever been.

‘That’s the risk that you end up with a generation or a large portion of Generation Z confined to the rental market, which obviously has long-term consequences because the main way to grow wealth in Australia is by owning real estate. ‘ he says.

“Many Australians are being denied that and it will leave them in a difficult financial situation for much of their lives.

‘It’s not a great situation – it’s creating social tensions and they could become more serious – it’s crucial that we solve this affordability problem.’

The lucky ones can inherit a house from their parents, but at a later stage of life.

“By the time that happens, you’ll be 55 or 60 or something; You may be able to pay off your mortgage at that age, but that is not ideal,” he says.

Those who do not come from wealthy families are increasingly at risk of becoming destitute in their old age, or falling into crippling debt if they even manage to enter the property market.

“It’s not a fair situation because your parents weren’t well off. You get nothing if they die,” says Dr. Oliver.

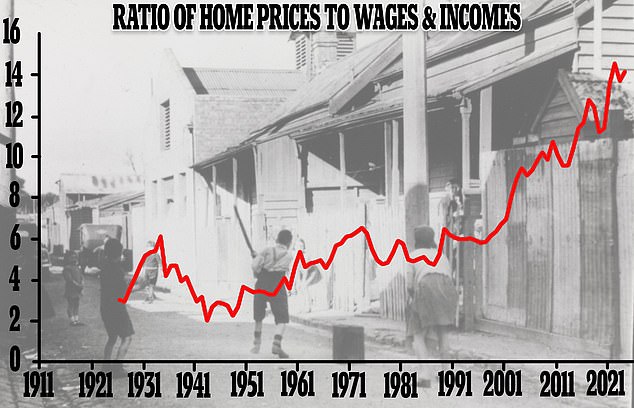

During the early 1930s, at the start of the Great Depression, a typical home cost only six times the average salary, but now it is thirteen times the average salary.

“You’re now seeing a lot more people retiring with higher levels of debt – that’s going to be a bigger problem.”

Although the 3.9 percent unemployment rate is nowhere near the 32 percent of 1932, it is much more difficult for a worker to buy a home compared to the decade prior to the war.

In the early 1930s, at the start of the Great Depression, a typical home cost just six times the average salary, but now it is thirteen times that amount.

To put that into perspective, homes in the Australian capital now have a median price of $1.009 million, which is out of reach for someone earning the average salary of $77,000.

That rules out the average worker buying a home in a suburb a medium distance from Melbourne or Brisbane, where prices have risen by double digits in the past year.

Sydney’s average house price of $1.471 million is 14.7 times Australia’s average full-time salary of $100,000 and 19 times the average wage of $77,000.

An AMP graph of data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and CoreLogic showed that the average house price during the war years was only twice the average salary.

During the 1950s, when Australia experienced a migration and baby boom, the ratio climbed to the level of four, before broadly stabilizing at around five to six until the late 1990s.

Younger Australians are truly worse off now than they were during the Great Depression – at least when it comes to housing affordability – with ever-increasing levels of immigration robbing future generations of an economic future (pictured is La Perouse in Sydney’s south-east during the Great Depression)

But over the past 25 years, housing affordability has deteriorated radically as levels of overseas migration have soared, tripling in the 2000s.

Net overseas migration levels rose from 111,441 in 2000 to 315,700 in 2008, as the Chinese-led resource boom led to governments from both sides of politics importing more skilled labor.

“What happened around the 2000s was there was a huge wave of immigration around 2006,” says Dr. Oliver.

“We had a wave of immigration without a commensurate increase in supply.”

This 2000s housing shortage has continued to worsen, with net overseas migration reaching a record high of 548,800 in 2023.

In 1931, Australia had a net overseas migration rate of minus 12,117, as more people left the country than entered permanently.

Australia’s net overseas migration rate did not climb to the six-figure mark until the early 1950s, before further tampering.

While the 100,000 level was revised again, the increases were only temporary for several years of the late twentieth century.

AMP chief economist Shane Oliver, who compared house prices in the capital with wages going back to the 1920s, tells me many younger people are likely to become lifelong renters, while housing affordability is the worst it has ever been (the photo shows a row of rental properties near Bondi in Sydney)

But in the 2000s, immigration levels remained consistently in the six figures until the 2020 pandemic, leading to homes costing more than ten times normal salaries in the 2010s.

Dr. Oliver says younger people can only be homeowners if governments on both sides of the aisle control immigration to ease the housing shortage.

“Part of that means controlling immigration levels or limiting population growth to be consistent with the ability to provide new housing.

More bosses could also hire staff outside major capitals or allow home working.

“The problem with the capitals is that they are already very expensive and already very busy,” says Dr Oliver.

“We need to look for ways to better decentralize and distribute our population across the country – that would also help provide more affordable housing.”

This could mean allowing more home working so that more younger people with bosses in the city can move to regional areas, taking advantage of a good idea that emerged during the pandemic before staff were recalled to the office.

“I don’t think we’ve made the most of it, but one way to encourage decentralization is to encourage more people to work from home where they can do so,” he says.

Our way of life is clearly under threat – and a repeat of the bad government policies of the past twenty years will only destroy the great Australian dream forever.