Fossils of the world’s largest dolphin have been discovered in the Amazon – an ancient creature was over 3 meters long when it swam the oceans more than 16 million years ago

Remains of the world’s largest dolphin have been discovered in the Peruvian Amazon, revealing that the mammal was up to 3 meters long.

The remains of an ancient species distantly related to the rare and endangered river dolphin have been discovered in the Peruvian Amazon.

Paleontologists from Switzerland’s University of Zurich (UZH) found that the fossils indicated the ancient creature was distantly related to the rare and endangered river dolphin that lives around South America.

The fossils suggested that the newly found Pebanista yacuruna had poor eyesight, an elongated snout and numerous teeth when it roamed the oceans more than 16 million years ago.

The team named the new species in honor of the mythical people known as Tacuruna, who reportedly lived in underwater cities around the Amazon basin.

The fossilized remains of an ancient dolphin believed to have lived 16 million years ago have been found in the Peruvian Amazon

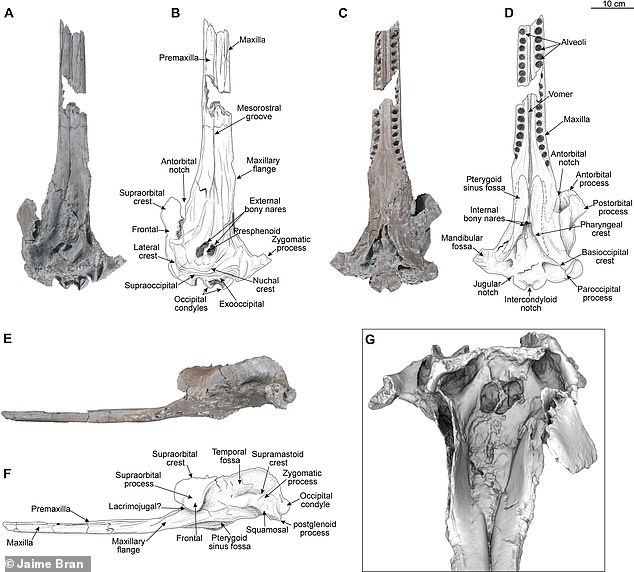

A team of researchers from the University of Zurich has found the skull of the largest dolphin ever discovered

Researchers first discovered the dolphin skull during an expedition to Peru in 2018, when they spotted the fossil protruding from the Napo River embankment.

Surviving river dolphins were “the remains of what were once very diverse groups of marine dolphins,” Aldo Benites-Palomino said. The guardadding that it is believed they left the oceans in exchange for freshwater rivers to find food sources.

“Rivers are the escape valve… for the ancient fossil we found, and that includes all the river dolphins alive today,” he said.

At the time when the ancient dolphin populated the oceans, the Peruvian Amazon had a very different landscape: it was covered with large lakes and swamps that covered Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru and Brazil.

Aldo Benites-Palomino first discovered the dolphin skull in 2018 in a dike of the Napo River in Peru

A changing climate caused the Pebanista to disappear, the researchers said, as their prey began to disappear and the lack of a food source pushed the dolphin to extinction.

About 10 million years ago, the waters of the Amazon flowed through sandstone westward, forcing the remaining lake water eastward.

At that point, the large lake began to dry up and become a river, changing the area from a moist and diverse ecosystem to an arid and sparser region.

“After twenty years of work in South America, we had found several gigantic forms from the region, but this is the first dolphin of its kind,” says Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra, director of UZH’s Department of Palaeontology.

‘We were particularly intrigued by its special biogeographical in-depth history.’

Benites-Palomino told it NewScientist that the region where he and his team found the fossil was once covered by an “insanely large” lake, “almost like a small ocean in the middle of the jungle.”

The dolphin’s small eye sockets led researchers to believe he had poor eyesight and Benites-Palomino told the newspaper: “We know he lived in very muddy water because his eyes started to get smaller.”

Researchers found that the Pebanista had an elongated snout and numerous teeth, indicating that the dolphin fed on fish, like many other species of modern river dolphins.

Benites-Palomino and his team expected the dolphin to be closely related to the modern Amazon river dolphin, but instead found that the raised crests on its head that aid in echolocation make it similar to the South Asian river dolphin.

Echolocation is an animal’s ability to “see” by listening to the echoes of its high-frequency sounds used in hunting.

“For river dolphins, echolocation or biosonar is even more important, because the waters they live in are extremely muddy, which obscures their vision,” says Gabriel Aguirre-Fernández, a UZH researcher and co-author of the study.

Finding fossils in the Amazon is becoming increasingly difficult because paleontologists must wait until the region’s “dry season,” when river levels are low enough to uncover fossilized remains.

Collecting the fossils is a time-sensitive process because if paleontologists don’t retrieve them from the dry season, rising river tides could sweep them away and be lost forever.