‘Forever’ cancer-linked chemicals found across Sydney’s drinking water catchment: What you need to know

An investigation has been launched after carcinogens, dubbed ‘eternal chemicals’, were found in Sydney’s drinking water areas.

Sydney Water confirmed in June that cancer-causing PFAS chemicals had been detected in catchments across the city.

The data showed that low levels of carcinogens were present at major filter plants, including Orchard Hills, Prospect Reservoir and Warragamba.

PFAS chemicals were also found in higher concentrations at the Cascade Dam in the Blue Mountains and in North Richmond, 70km northwest of the CBD.

The PFAS concentration levels fall within Australian drinking water guidelines, but are above the limit the United States now considers safe to drink.

In April, industrial conglomerate 3M was sued for “misleading” the American public about the presence of PFAS chemicals in their drinking water.

PFAS is a term used for thousands of substances that are considered “perpetual chemicals” because they never break down in the environment.

The chemicals found in Sydney’s tap water have been used in textile protective equipment, packaging and firefighting foam. Sydney Morning Herald defeated.

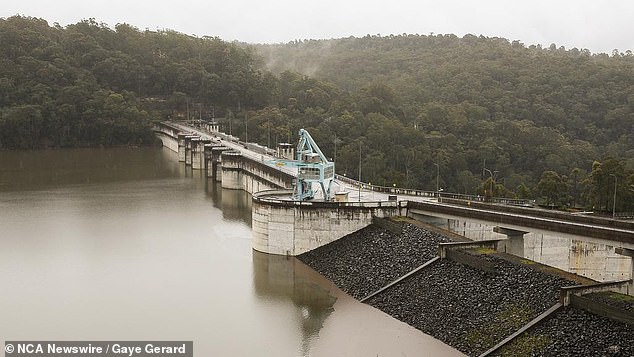

New data from Sydney Water has revealed low levels of carcinogens at major filter plants including Orchard Hills, Prospect Reservoir and Warragamba (pictured)

Sydney Water has confirmed that PFAS chemicals linked to cancer have been found in catchments across the city (pictured Water NSW at the Warragamba Dam)

PFAS chemicals were found in five of nine water catchments sampled by Sydney Water, with Cascade measuring more than 10 ppt (parts per trillion) of PFAS.

These concentrations are four times higher than the maximum limit at which PFAS can be removed from drinking water in the US, prompting a new round of testing.

The Cascade water treatment plant supplies water to up to 30,000 people, while PFAS levels in Katoomba and Blackheath are higher than other locations.

2+ ppt PFAS were detected at water treatment plants in Orchard Hills, North Richmond, Prospect and Warragamba.

However, no measurable levels of PFAS were found in the Macarthur, Nepean, Woronora River or Illawarra catchments.

The results of the tests carried out by Sydney Water mean the country’s largest water company will now carry out monthly tests in “potentially affected areas”.

This measure contradicts Sydney Water’s previous position that there are no PFAS hotspots in the city’s drinking water catchment areas.

‘All tested samples are well below [Australian drinking water] guidelines’ … and ‘drinking water monitoring uses a risk-based approach,’ a Sydney Water spokesperson said.

‘There is regular consultation between Sydney Water, WaterNSW and NSW Health to assess potential risks to Sydney’s drinking water supply from PFAS or other contaminants.’

However, experts say an urgent investigation into PFAS in Australia should be a priority.

The results of Sydney Water’s latest tests will be “confronting” for many, according to Ian Wright, a water pollution expert at the University of Western Sydney.

“This also contradicts the authorities’ statements that there is no PFAS risk in the catchment. Without any doubt, more regular testing is needed and this should be made public,” the expert told the Herald.

PFAS is a term used for thousands of substances that are considered ‘forever chemicals’ because they never break down in the environment (pictured: Warragamba Dam)

High levels of PFAS have been found in the livers of platypuses in coastal New South Wales, suggesting the chemicals may be accumulating and spreading (stockpiling)

His warning comes after high levels of PFAS were found in the livers of platypuses in coastal New South Wales, suggesting the chemicals could be building up and spreading.

Some of the monotremes with levels of the ‘eternal chemicals’ were found in areas where there are no known PFA hotspots nearby.

The research, led by Katherine Warwick, a PhD candidate at the University of Western Sydney, studied the bodies of nine platypuses from different regions.

Researchers found that all of the native animals had traces of PFAS in their bodies, except for one captive platypus that had been drinking filtered water at Taronga Zoo.

One of the platypuses found dead in the Wingecarribee River watershed had 390 micrograms of PFAS per kilogram in its liver.

“The levels are very, very high,” Dr Wright told the Herald.

Previous studies have shown a link between PFAS and liver damage, birth defects and weakened immune systems in other animal species.