Talk about a lucky escape! Incredible footage reveals how swallowed eels can wriggle their way out of their predator’s stomachs

From camouflage to poison, animals have developed dozens of ingenious ways to avoid being eaten.

However, researchers have now discovered that the Japanese eel has a gift that takes its ability to evade the jaws of death to a whole new level.

This incredible video shows the shocking moment an eel ‘turns’ and disappears from its enemy’s stomach after being eaten.

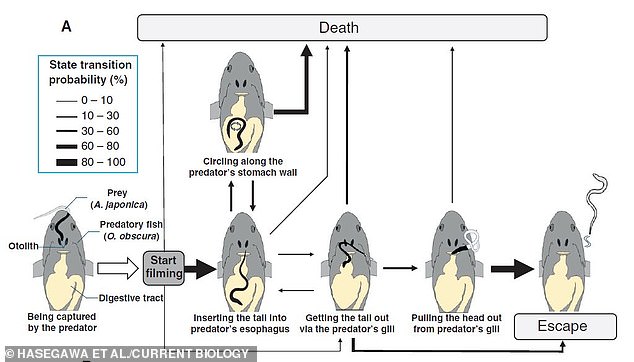

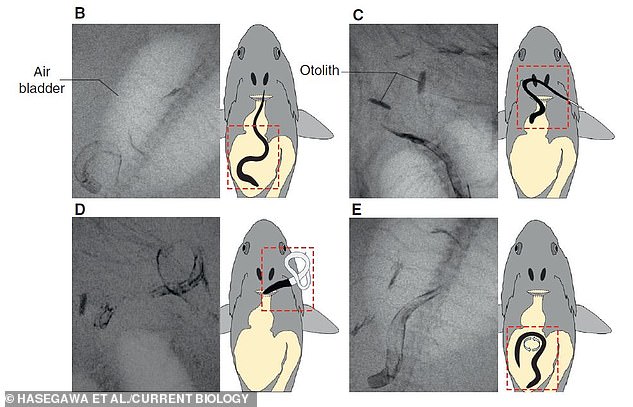

Scientists at Nagasaki University have developed a new X-ray video method that has captured the first images of eels making their way to freedom by slipping through a fish’s gills.

Lead researcher Professor Yuuki Kawabata told MailOnline: ‘Contrary to our expectations, it was truly astonishing for us to see the eels desperately escaping from their predator’s stomach to their gills.’

Researchers from Nagasaki University have created a bizarre X-ray video showing young eels escaping from the stomach of their predator

In an earlier study, Professor Kawabata and her colleagues had already observed that some young Japanese eels could escape from the stomachs of other fish.

Until now, however, they had no idea how the eels were able to accomplish this bizarre escape attempt.

The researchers spent a year developing a new method for X-ray videography, which allowed them to see what was actually happening to the eel in the fish’s stomach.

Eels were injected with a contrast agent called barium sulfate, which made their thin bones visible on an X-ray of the fish’s intestines.

During the experiment, 32 young eels were injected with the chemical before being fed to a native predatory fish, the so-called ‘dark sleeper’ or odontobutis obscura.

Like many other predatory fish, the moth swallows its prey whole, along with the surrounding water, by quickly opening its mouth.

The researchers had observed that Japanese eels (pictured) could escape from the stomachs of their predators, but until now they did not know how this was possible

Once inside, the prey is deposited in the stomach, where it is killed in an average of 211 seconds due to the acidic, oxygen-free environment.

However, when it turned out that this was not the case, images were taken of the fish’s stomach.

Professor Kawabata says that before the experiment they expected the eels to try to escape directly through the predator’s mouth and enter through their gills.

Professor Kawabata says: ‘The most surprising moment in this study was when we saw the first images of eels escaping by returning through the digestive tract to the gills of the predatory fish.’

Instead of ending up in the mouth, the researchers saw that the eels pushed their tails through the esophagus directly into the gills.

From there, the eels would twist their bodies so they could pull their heads free and swim away.

The researchers saw that some eels circled the fish’s stomach. Of the eels tested, 13 were able to push their tails through the gills and nine were able to escape completely.

‘We discovered a unique defense tactic in young Japanese eels using an X-ray camera system: they escape from the predator’s stomach by returning to the digestive tract towards the gills after being captured by the predator.’

In their paper, published in Current Biology, the researchers suggest that the eels’ long bodies likely cause their tails to become lodged in the esophagus.

Of the 32 eels tested, all but four attempted to force their way out of the fish’s digestive tract. Thirteen eels were able to free their tails, and nine eels were able to escape completely.

On average, the eels were able to escape the dark sleeper’s gills within 56 seconds of being swallowed.

A number of eels also showed ‘circling’ behaviour, running around the stomach of the predatory fish as if looking for a way out.

32 eels were injected with barium sulphate to make them visible under X-rays and then fed to a native predatory fish, a so-called ‘dark sleeper’ (see photo)

Only the eels that made the transition to inserting their tails through the esophagus were actually able to escape death.

The researchers note that the fish are apparently aware that their dinner is trying to escape and often try to fight back

Co-author Yuha Hasegawa told MailOnline: ‘Many predatory fish display resistance behaviour by re-swallowing the escaping eel, taking water into their mouths and expelling it through their gills.

‘The eels could use this water current to escape from the predators through their gills.’

However, the predatory fish do not seem to be bothered by the escape attempt.

Using an X-ray camera, the researchers discovered that the eel pushed its tail into the fish’s esophagus before disappearing back out of the gills.

Because larger eels were more likely to escape, the researchers believe it is vital that young eels quickly develop the strength and motor skills they need to escape.

Dr. Hasegawa says: ‘This discovery has given us new insights: muscle strength and tolerance to highly acidic and anaerobic environments, as well as their elongated and smooth morphology, are necessary for eels to quickly escape the digestive tract before being digested.’

In the future, the researchers hope that this X-ray technology will be useful for further studies into how prey can escape after being eaten.