Fight against cancer must undergo a ‘fundamental reset’, leading doctors warn as they unveil 10-point plan to improve care in the UK

Cancer care needs a ‘fundamental reset’ to improve care and prevent more patients from dying, leading doctors have warned.

The group of senior clinical cancer specialists is calling for the development of radical cancer control plans to make the system ‘fit for the future’.

They estimate that there will be up to 2,000 extra cases of cancer per week by 2040, but warned that Britain is already failing to keep pace with other countries.

Writing in the Lancet Oncology, they said Britain’s poor performance compared to other countries shows that our approach to cancer care contradicts international consensus and ‘isn’t working’.

With all UK countries in the bottom half of the cancer rankings, they argued that a fundamental reset is needed to reverse the problem.

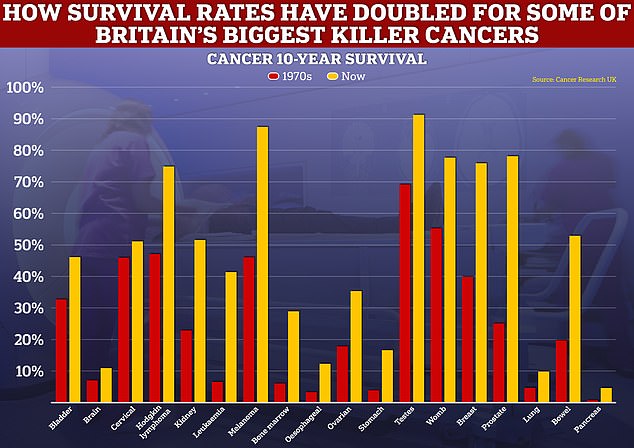

The group of senior clinical cancer specialists is calling for the development of radical cancer control plans as they anticipate the need for a cancer service ‘fit for the future’. According to Cancer Research UK, ten-year survival rates for common cancers have now surpassed 50 percent, and experts say further improvements can be made in the coming decade.

In Lancet Oncology they said that Britain’s poor performance compared to other countries shows that our approach to cancer care contradicts international consensus and ‘doesn’t work’. With all UK countries in the bottom half of the cancer rankings, they said a fundamental reset is needed to reverse the problem

The article outlines a ten-point plan to improve cancer care and calls for the creation of a national cancer control plan for the whole of the UK, along with a prevention program for smoking, obesity and alcohol consumption.

This includes establishing a National Cancer Research Institute, broadening cancer research and delivering the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan to increase workforce levels.

They said meeting the key treatment target of 62 days is essential to ensure patients receive timely care, and urged the integration of hospice care into the NHS.

It comes after the government unveiled plans to integrate its national cancer control plan into the Major Condition Strategy, which was launched in January 2023.

The blueprint will aim to improve health outcomes over the next five years and will cover cancer, heart disease, musculoskeletal conditions, poor mental health, dementia and respiratory conditions.

Mark Lawler, chairman of the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership, said it was akin to “abandoning” a national cancer, describing it as “an incomprehensible decision that is not in the best interests of people with cancer.”

Professor Richard Sullivan, co-senior author and director of the Institute of Cancer Policy at King’s College London, said: ‘Cancer must be a top political priority for the whole of Britain.

‘We need care that is clinically led and truly personalised. The inability to develop specific and well-funded cancer plans with a fit-for-purpose research agenda is also leading to increasing patient inequalities, healthcare workforce burnout and poor outcomes.

‘All the ingredients are there to tackle these problems. But we need political will.”

Pat Price, a visiting professor at Imperial College London and co-senior author, said cancer care is “fast becoming a monumental crisis” without a “realistic plan.”

She added: ‘A cancer plan is not just a strategy, it is a lifeline for the one in two of us who will develop cancer. Cancer patients are continually being failed, with cancer survival outcomes in the UK still at the bottom of the cancer rankings.

“We need to tackle the cancer workforce crisis, deliver treatments on time and end the situation where we are lagging behind in cancer technologies in key areas such as radiotherapy.

‘The urgent need for a cancer-specific control plan is clear, and it is unbelievable that doctors should create one themselves instead of the government.’

The authors estimate that by 2040 there will be between 457,000 and 564,000 cancer patients in Britain each year, an increase of 30 percent.

Earlier this month, data published by NHS England showed that there had been 257,702 urgent cancer referrals from GPs in September, down 4 per cent from 267,555 in August, but up 1 per cent year-on-year from 254,455 in September 2022.

However, the percentage of people visiting a specialist within two weeks of an urgent referral has fallen from 74.8 percent to 74.0 percent, leaving it below the 93 percent target.

Of cancer patients who received their first treatment in September after an urgent referral from their GP, 59.3 percent had waited less than two months, compared to 62.8 percent in August and behind the 85 percent target.

While the level of progress in cancer survival has been rapid in some forms of the disease, such as breast and prostate cancer, others, such as those in lung and pancreas, have improved only at a snail’s pace.

In August, the government and NHS England confirmed plans to streamline cancer waiting time targets.

Officials said the new standard, which was implemented in October, will abandon the “outdated” two-week wait goal and be replaced by the Faster Diagnosis Standard.

The ten previous targets will be merged into three, with patients with suspected cancer expected to have the disease diagnosed or ruled out within 28 days.

Elsewhere, the 62-day referral to treatment will ensure that patients who have been referred and diagnosed with cancer must start treatment within that time frame, while patients with a diagnosis and a decision has been made about their first or subsequent treatment , have to start doing this within 31 years. to dawn.