Experts slam ‘alarmist’ study claiming mothers stressed during Covid pandemic had ‘stunted’ babies with smaller brains

Pregnant women stressed during the Covid pandemic had babies with smaller brains, according to the results of a study that was immediately labeled ‘alarming’ by British experts.

Scientists from the Children’s National Hospital in Washington DC claimed that their study, which involved 150 mother and baby pairs, found a significant reduction in brain size in babies born to mothers who scored high stress scores during the pandemic.

This included reductions in the brain’s white matter, an inner part of the brain responsible for processing information, the hippocampal area, which controls learning, and the amygdala, areas that control emotions.

The study authors claimed that this ‘growth delay’ could lead to babies being more likely to suffer from problems such as anxiety later in life.

However, British specialists have poured cold water on the conclusion, saying it is ‘not supported by the data’.

Scientists from the Children’s National Hospital in Washington DC claimed that their study of around 150 mother and baby pairs found a significant reduction in brain size in babies born to mothers who scored high stress scores during the pandemic (stock image)

The study compared the maternal stress scores of two cohorts of mothers – 103 pre-pandemic and 56 during the pandemic – with brain scans of their babies.

Mothers in the Covid group were about three times as likely to score above thresholds measuring anxiety, stress and psychological distress, compared to their counterparts before the pandemic.

Their babies’ brains were up to 0.3 cm smaller in the white areas of the brain and the hippocampus.

The amygdala, the emotional processing centers in the brain, was up to 0.5 cm smaller in babies born to the stressed pandemic mothers.

But Professor Grainne McAlonan, an expert in neuroscience at King’s College London, said the findings should be treated with caution.

“In my opinion, this article unfairly uses alarmist language and is not specifically an article about Covid,” she said.

‘Rather, it is a paper about the possible response of the early brain to maternal stress during pregnancy, and it is not surprising that stress was higher during Covid.’

She added that although the paper found differences in the brain, the authors had failed to demonstrate what these actually meant.

‘Whether this difference is clinically meaningful has not been established, there are no childhood outcomes, so assigning a value to differences in brain volume using words like ‘immature’ is completely inappropriate and not supported by the data’ , she said.

‘In general, larger brain areas are not necessarily better in brain imaging studies unless there is a clear relationship between brain size and brain function. The authors do not look at this.

‘All that has been shown here is a possible response of the brain to maternal stress during pregnancy, and a very small effect at that. We can’t say whether it’s good or bad.’

Professor McAlonan also pointed out that data on pandemic mothers was collected between 2020 and 2022.

She said this was a long period of difference and that mothers who became pregnant during the height of the 2020 lockdowns likely had a very different experience to those carrying babies in 2022.

Another flaw she found was in the way mothers’ suffering was measured, namely whether they scored high on a self-reported threshold.

“Distress is complex, variable and exists on a continuum, and using these types of cutoffs may not be optimal,” she said.

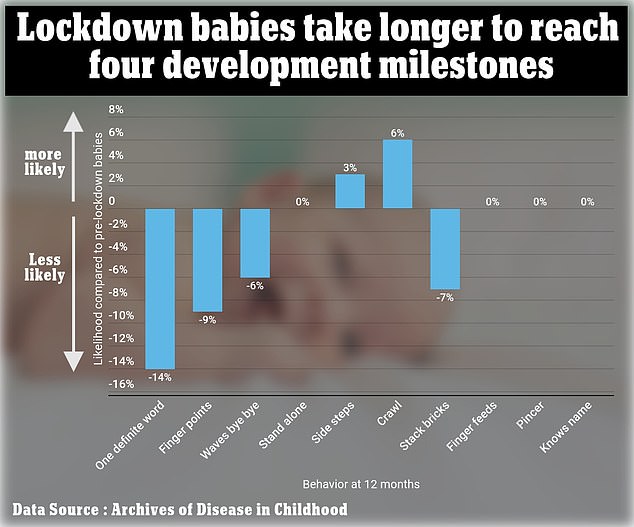

The graph above shows the likelihood of certain behaviors in pandemic babies compared to non-pandemic babies on their first birthday. Pincer refers to using the thumb and index finger together. Babies during a pandemic would crawl more often, but talk, point or wave goodbye less often

However, she added that more work needed to be done to answer whether the observed differences in babies’ brains would indeed lead to changes in their future development.

None of the women in the smaller pandemic cohort tested positive for the virus during pregnancy.

The authors acknowledged that their study is small and that the fact that it consists mainly of white, highly educated women may be less relevant to other populations.

Previous studies have linked stress during pregnancy to changes in the way babies’ brains develop, which can cause emotional problems later in life.

British researchers previously linked higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol in mothers to structural changes in the amygdala of newborn babies.

Cortisol is involved in the body’s response to stress – with higher levels indicating higher stress – and also plays a role in fetal growth.

The amygdala – of which there are two in each hemisphere – is known to be involved in emotional and social development in childhood.

Multiple studies have also tried to find out if and how babies born in the Covid years differ from their peers, and many have uncovered mixed results.

Some have discovered that they have an altered gut microbiome – the ecosystem of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ bacteria in the digestive system – which may give them fewer food allergies and a stronger immune system.

Others have found negatives, such as that young people born during the pandemic were less likely to say their first words on their first birthday compared to babies born before Covid or point to objects.

Experts have theorized that the above observations may be due to the fact that wearing a mask during a pandemic has limited children’s ability to read facial expressions or see people’s mouths move, as well as a reduction in socialization during lockdowns .