Experts says WWII diary about lost Nazi millions is a ‘complete forgery likely produced after 1982’

>

Experts analysing a WWII diary said to reveal the location of hidden Nazi treasure in an 18th century palace in Poland have concluded it is a ‘complete forgery’.

Presenting their findings in their monthly magazine, the group said: ‘The War Diary is a Polish-German forgery likely produced some time after 1982.’

The diary, said to have been written by an SS officer who noted down the location of looted works of art and valuables hidden towards the end of WWII, was acquired by a group calling itself the Silesian Bridge Foundation.

Since last year they have been digging up an old palace in the Polish village of Minkowskie where they believe £200m worth of Nazi gold is hidden.

Since May last year, the ‘WWII diary’ has been in the hands of a group called the Silesian Bridge Foundation – who have been digging up the grounds of an 18th century palace in the Polish village of Minkowskie where they believe £200million of Nazi gold

The diary claimed to show the hiding places of treasures intended for the creation of a Fourth Reich to continue the war, but experts now believe the entries are forgeries from the 1980s

But after going through the diary, historians from the Discoverer organisation in the Polish city of Wroclaw said they found ‘conclusive proof’ that the whole thing was fake.

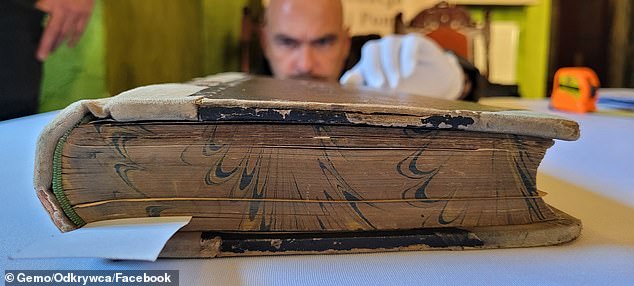

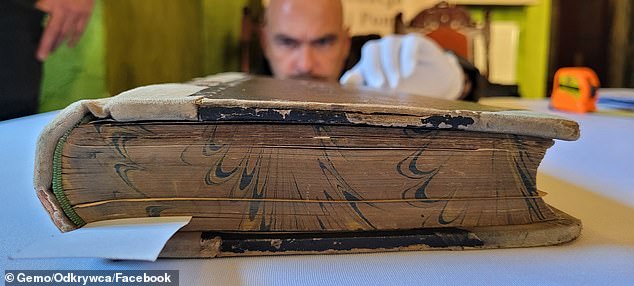

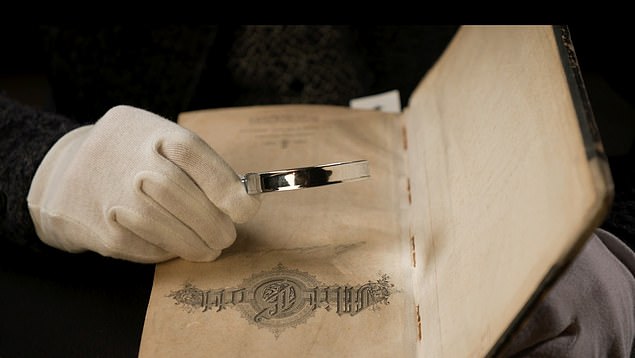

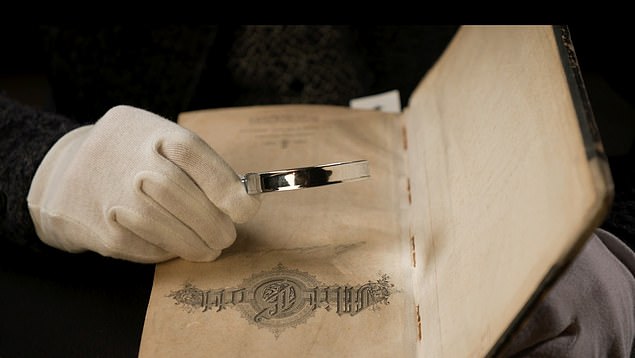

The organisation’s Łukasz Orlicki told the Polish Press Agency: ‘It turns out that the diary is an accounting book from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries with almost 600 pages, the vast majority of which are blank.

‘There are simply accounting entries from the beginning of the 20th century, but on page 100 the notes of the alleged German officer appear.

‘The records containing the history of hidden valuables and works of art cover only nine pages. They are written in pencil.

‘At first glance it looks to have come from the period. The content contains information about four caches; the entire content of the notes can be divided into a narrative part containing information about events from the Lower Silesia and Opole region at the end of World War II, and the deposit part, i.e. descriptions of where valuables are hidden.

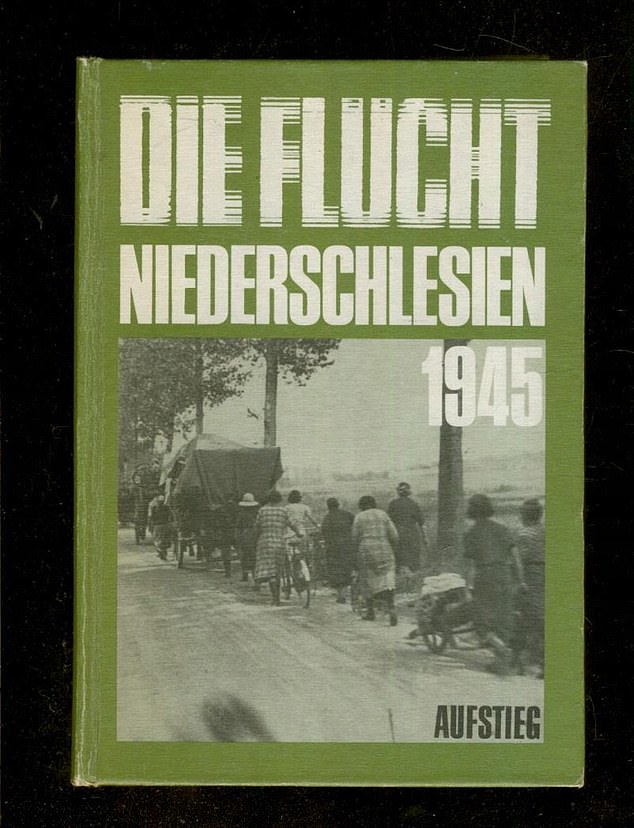

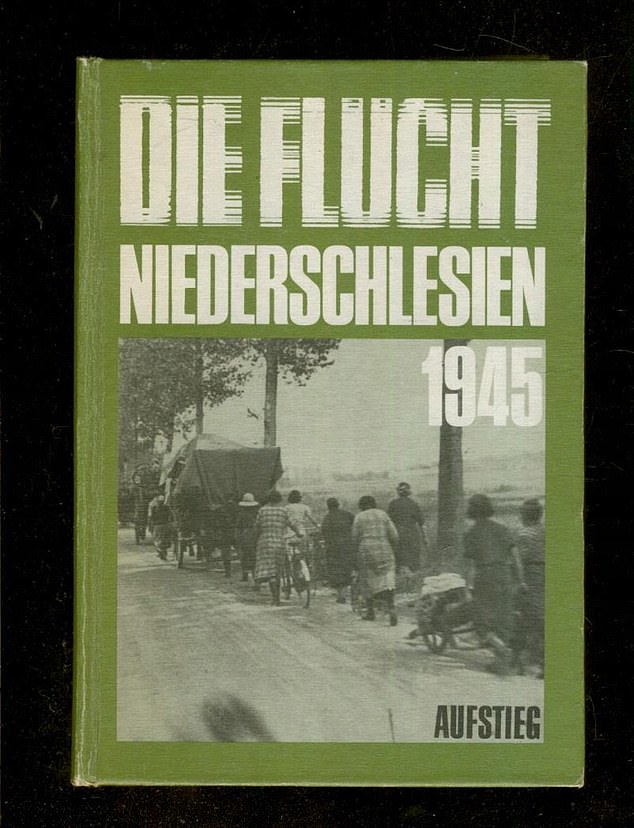

‘But the events contained in the diary were copied from the accounts of German refugees who fled from Lower Silesia in 1945.

Treasure hunters failed to find 10 tonnes of gold in the grounds of the 18th century palace in Minkowskie, southern Poland

Large parts of the diary are believe to have been copied verbatim from this book, which described the accounts of German refugees who fled from Lower Silesia in 1945

‘These were accounts written down after the war, which were in German archives.

‘After comparing the content, it turned out that someone had copied word-for-word into the journal fragments of these accounts that were published in Germany several decades after the war.’

He added: ‘This is one of the irrefutable proofs that the so-called diary was written by an unknown person in the 1970s at the earliest.’

According to the Silesian Bridge Foundation, they received the diary from a man claiming to be the son of a SS officer and represented a Masonic Lodge made up of the descendants of Nazi officials seeking atonement.

According to legend, the treasure was stored in police headquarters and packed into crates before being transported under SS guard from Breslau, in what is now the Polish city of Wrocław, towards Hirschberg, today’s Jelenia Góra, and the Sudeten mountains.

The treasure dubbed the ‘Gold of Breslau’ is thought to include jewellery and valuables from the private collections of wealthy Germans who lived in the region and who handed their possessions to the SS to protect them from being looted by the advancing Red Army.

Soon after, the trail went dead and the gold was never seen or heard of again.

According to the Silesian Bridge Foundation, they received the diary (pictured) from a man claiming to be the son of a SS officer

The dig took place in the grounds of the 18th-century palace in the village of Minkowskie, Poland

According to the Foundation, a letter written by a senior SS officer to one of the girls who worked at the palace and who later became his lover revealed the treasure was buried in the palace.

The officer wrote: ‘My dear Inge, I will fulfil my assignment, with God’s will. Some transports were successful.

‘The remaining 48 heavy Reichsbank’s chests and all the family chests I hereby entrust to you.

‘Only you know where they are located. May God help you and help me, fulfil my assignment.’

In November last year, the historians who had been invited by the Silesian Bridge Foundation to ‘verify’ the diary said their initial findings ‘weren’t positive’.

Talking to local media at the time, they said: ’Our most important finding is that the village of Minkowskie is not mentioned in the ‘War Diary’.

‘This may be hard for the Foundation, because it is the only place their excavation works are being carried out at this moment.’

The historians who examined the documents have also questioned the authenticity of the letter.

They said: ‘The corresponding documents, like one famous letter, do not seem very ‘legit’ and are not a part of the ‘War Diary’, meaning there is not even one bit of evidence that there is anything in Minkowskie.’

The Silesian Bridge Foundation responded saying: ‘Documents of that age and type leave a lot of room for interpretation, we are aware of that.

‘It is our belief that War Diary will always defend itself.

‘We are very confident about it which is why we welcomed your team and we are open to other experts as well.

‘Thank You!’

The experts examining the letter and diary admitted that some of the people mentioned did exist and that led credence to the claims.

But they then found a book published in Germany after the war about escapees from the region which they say ‘contained the same details which were then copied verbatim into the diary.’

According to the historians, the passages in the diary were transcribed from accounts of German refugees who fled Lower Silesia in 1945 which were later published in the 1960s in a book called Die Flucht (The Flight).

“The result of our analysis unequivocally identifies the war diary as a fictional text created many years after the war.”