Evidence of 4,000-year-old ‘lost’ civilization is discovered in South America

Archaeologists have found evidence of a lost civilization that lived in South America at least 4,000 years ago.

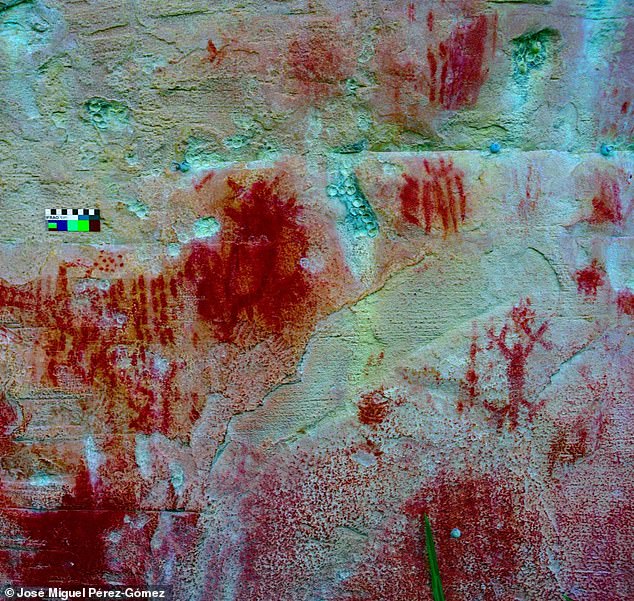

They discovered ancient drawings on a flat mountaintop in Venezuela. These drawings featured colorful patterns of dots, leaf motifs and stick figures that may have been part of a mysterious ritual.

Lead researcher José Miguel Pérez-Gómez told DailyMail.com that previous surveys had found no signs of human activity in the region, suggesting the art was created by a previously unknown civilisation.

The distinction between the newly discovered group and other cultures is based solely on “style comparisons with other sites in the region,” suggesting that this could be “the starting point of the emergence of this culture.”

Archaeologists have found evidence of a ‘lost civilization’ in Venezuela, depicting ancient rituals in 4,000-year-old drawings

The rock paintings were discovered on a mountain in Canaima National Park, which could be ‘ground zero’ of where indigenous culture first developed

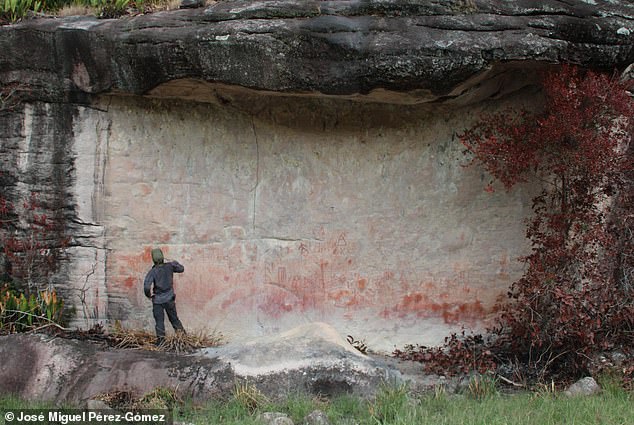

The rock paintings were discovered in Canaima National Park in the state of Bolivar and cover an area of over 29,000 square kilometers.

“What we see is a new culture of hunter-gatherers who probably arrived in the area of the Canaima National Park at the end of the Pleistocene,” Pérez-Gómez said. “That area existed between 2.5 million and 11,700 years ago.”

‘They settled there, developed there, and then spread throughout the rest of the region, all the way to the Amazon basin.’

Some of the drawings, such as one that appeared to show a leaf, are in places that are difficult to reach and “lie on a clean, oval rocky space that may have inspired the artist to create this particular design,” according to the study published in the log Research into rock drawings.

The hunter-gatherers used red ochre, a natural oxide pigment made from ground clay, quartz and chalk, which had a light orange hue.

Other motifs resembled claviformes, a club-shaped symbol or image, with blurred figures below and around it. These could indicate successful hunting activities.

According to the study, more research is needed to understand the meaning behind the drawings and their representation.

“Style comparisons to date show similarities with rock art on the Brazilian border, dated to about 4,000 years ago,” he continued. “However, the new rock art is much cruder, suggesting it could be even older.”

The artwork featured stick figure drawings of people, dot patterns and striking leaf motifs on a rock face that may have been used as shelter for indigenous hunter-gatherers and as a site for performing ritual activities.

Researchers aren’t sure why ancient people created this art, but it could have something to do with birth, illness, nature, or hunting.

Although some of the drawings showed signs of organic disturbance, such as lichen, algae, roots or wasp nests, the archaeologists noted that the overhanging portion of the rock face had preserved the panels

Although some of the drawings showed signs of organic disturbance, such as lichens, algae, roots or wasp nests, the archaeologists noted that the overhanging part of the mountain had preserved the panels.

“These findings are exceptional because they are new to science and fill a gap in an area that has never been studied archaeologically before,” Pérez-Gómez said.

“They also provide context for other regional studies in northern Brazil, the Guianas, and even southern Colombia.”

According to Pérez-Gómez, the images could have been related to birth, illness, nature or hunting, but the location “probably had a meaning and an importance in the landscape, just as churches have a meaning for people today.”

The location of the mountain indicates the kind of people who made the drawings. The mountain is located between the Arauak and Aparuren rivers, which flow in opposite directions.

The secondary river connects to the Tirica River, which flows into the Caroni River, placing the mountain “in the middle of a natural corridor in this valley for wildlife migration,” the study said.

Some of the drawings were in inaccessible places, requiring the team to climb a ladder to photograph them

The hunter-gatherers used red ochre – a natural oxide pigment made from ground clay, quartz and chalk – which had a light orange hue

The researchers have called for protection of the site and are optimistic that they will discover more rock art in the park, which covers 11,583 square miles.

Pérez-Gómez noted that faded graffiti was also found on the rock face dating back to 1947 and believed to belong to Spanish explorer Captain Felix Cardona Puig, who discovered the area.

Fragments of pottery and stone tools have also been found in the area, suggesting that these may have been used by the hunter-gatherers who created the art.

“All this evidence points to the fact that we are dealing with a new culture,” Pérez-Gómez told DailyMail.com.

Some motifs resemble claviformes, a club-shaped image or symbol, with blurred figures below and around it, which could be a sign of successful hunting attempts.

Some drawings, such as the one that appears to show a leaf (pictured), are in places that are inaccessible and are ‘placed on a clean, oval rocky space, which may have inspired the artist to create this particular design’

Pérez-Gómez and are working with researchers in neighboring countries to determine whether the same cultural groups created the rock art

He and his co-author have called for protection of the site and are optimistic that they will discover more rock art in the park, which covers 29,000 square kilometers.

“The park itself is larger than countries like El Salvador or Belgium, so it would not be surprising if more traces are found if the investigation continues in more depth, depending on the sources,” Pérez-Gómez said. Axios.

The duo are working with researchers in neighboring countries to determine whether the same cultural groups created the rock paintings.

“This is not only relevant for Venezuela, but also points to a cultural and ethnic richness that will strengthen the way we think about the region globally,” Pérez-Gómez said.