Europe is entering a new world after the crippling energy crisis of the past

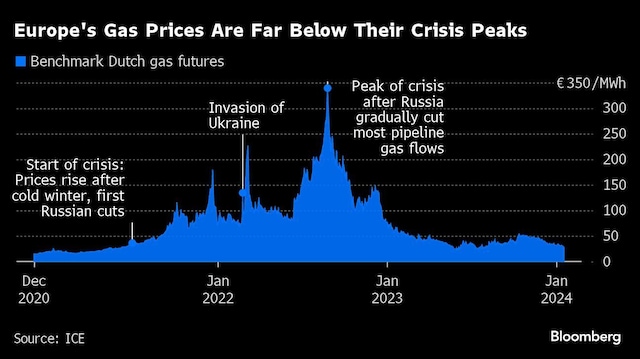

The decline in gas prices from the 2022 peaks has not always been one-way | Bloomberg photo

This month, a cold front swept across much of Europe and giant tankers carrying fuel through the Red Sea were diverted to prevent escalating violence. That should have caused gas prices to rise. Instead, they just kept falling.

Although it is a step too far in bringing clarity to Europe, it is a strong sign that the worst nightmare that sent energy bills soaring and pushed inflation to multi-year highs is a thing of the past.

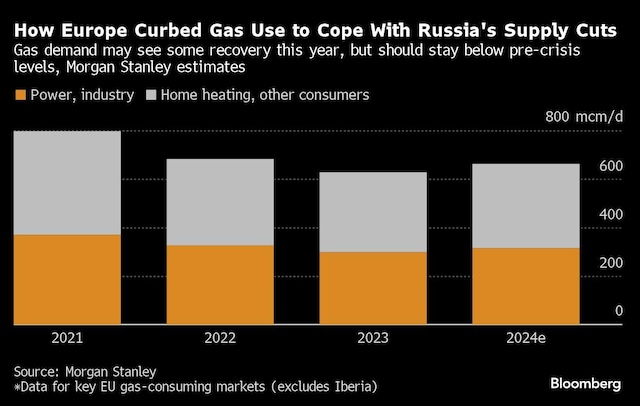

Europe is benefiting from record gas reserves amassed last year, along with the help of renewable energy sources and a relatively mild winter – apart from some cold spells. Slow economic growth also plays a role, slowing down energy demand in major industrial powers such as Germany.

That’s been enough to boost confidence among trade agencies that the region is stable enough to get through the rest of the winter with gas in reserve. European benchmark prices are currently trading below €30 per megawatt hour, about a tenth of peak levels in 2022.

Yet, having weathered the crisis, Europe has found itself in a new reality that comes with its own list of challenges.

The country now relies more on renewable energy sources and will experience the variability of that energy generation. The loss of Russian gas, on which it was overly dependent before the invasion of Ukraine, also forced the country to look elsewhere to meet its fuel needs. That means competing for a share of foreign liquefied natural gas cargoes with other parts of the world.

“Just by looking at prices it looks like the crisis is over,” said Balint Koncz, head of gas trading at MET International in Switzerland. “However, we are now dependent on global factors, which can change quickly.”

“Prices could rise again even in this heating season if there is a sudden supply disruption or an extended period of cold weather,” he said.

A key risk is the Middle East, amid attacks on ships in the Red Sea, a route Qatar uses to send LNG to Europe. Oil and gas tankers avoid the area, choosing to sail around the southern tip of Africa. According to data from Kpler, on a normal day about two to three LNG ships would use the passage.

Alternative energy

Gas prices are down nearly 60% in 2023 and are down another 12% so far this year, which should help lower consumers’ energy bills.

In Britain, the state-regulated price ceiling will fall by almost 14% in the spring, consultancy Cornwall Insight estimated in December.

“This is the second winter Europe is experiencing without Russian gas,” said Kim Fustier, head of European oil and gas research at HSBC Holdings Plc. “The fact that there is now a precedent – the winter of 2022-2023 which went off without a hitch – helps calm traders’ nerves.”

The expansion of renewable energy in Europe means a decreasing share of gas in the continent’s energy mix. An increase in the number of wind turbines and solar installations has helped reduce the need for fuel, along with a recovery in French nuclear production last year.

But there is still a long way to go, with many potential bumps. A gas pipeline transit deal between Russia and Ukraine expires at the end of this year – and is unlikely to be renewed – meaning the continent could get even less gas from Russia. Although there are huge investments in LNG worldwide, much of the new capacity will only come onto the market in 2025 and 2026.

And extreme weather events are becoming more common, putting pressure on energy systems and sometimes increasing demand for gas.

In Asia, strong supplies mean that gas prices are also currently falling, and are at the lowest level since June. LNG buyers in Japan, the world’s second-largest importer of super-chilled fuel, are actively selling off shipments because they have too much. Some of these shipments will probably find their way to Europe.

While there is demand, especially in India and China, these purchases are mainly driven by traders looking for a good deal.

The story is much the same in the US, where gas futures fell about 20% last week as markups remain well above the five-year average. The cold weather boosted energy demand and froze some gas wells, but did little to boost future demand.

Channel disruption

Yet problems at two key LNG passages – the Suez Canal and the drought-hit Panama Canal – are making journeys longer, raising the cost of shipping and expanding the global fleet of ships. While traders don’t seem too concerned about this, a prolonged disruption could change that.

The decline in gas prices from the 2022 peaks was not always one-way.

Intense bouts of volatility – from LNG strikes in Australia to outages in the US and the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas – have caused spikes, reminding us that the current calm is not guaranteed to last.

“We are still very cautious about what will happen next,” Stefan Rolle, head of energy policy at the German Energy Ministry, said Thursday at the Americas Energy Summit in New Orleans.

First print: January 21, 2024 | 12:55 pm IST