Egypt’s greatest pharaoh found more than 3,000 years after his death: long-lost sarcophagus is discovered under the floor of a monastery

The long-lost sarcophagus of ancient Egypt’s most powerful pharaoh has been found more than 3,000 years after his death.

Archaeologists re-examined a mysterious granite burial found beneath the floor of a religious center in east-central Egypt and discovered that it belonged to Ramses II.

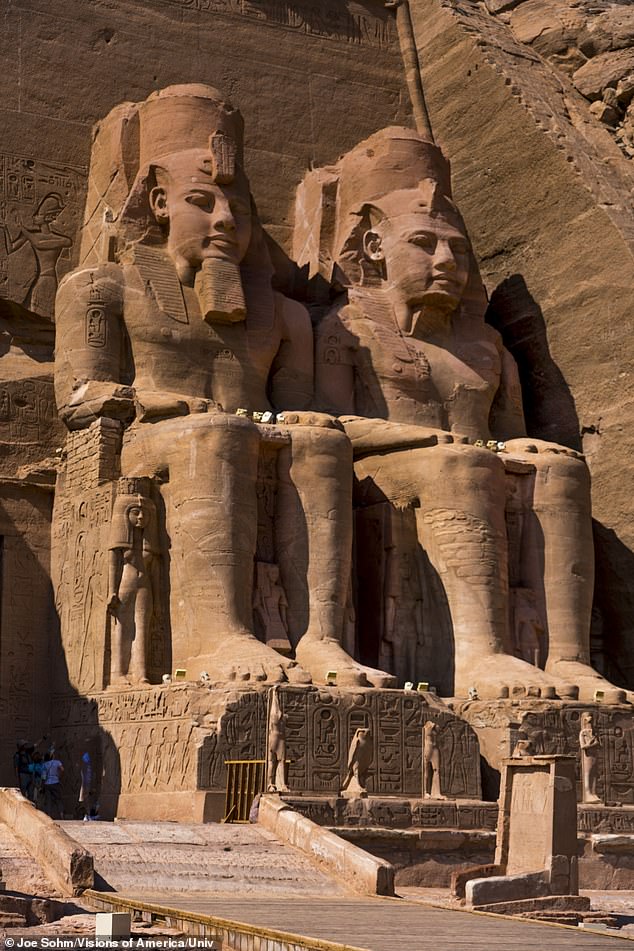

During his reign from 1279 to 1213 B.C. colossal statues and buildings were erected in what was marked as the final pinnacle of Egyptian imperial power.

The remains of a high priest were originally found in the sarcophagus, but that new discovery suggests he removed the pharaoh’s mummy and coffin for reuse in the burial.

Archaeologists have re-examined a mysterious granite burial found beneath the floor of a religious center in east-central Egypt and discovered that it belonged to Ramses II.

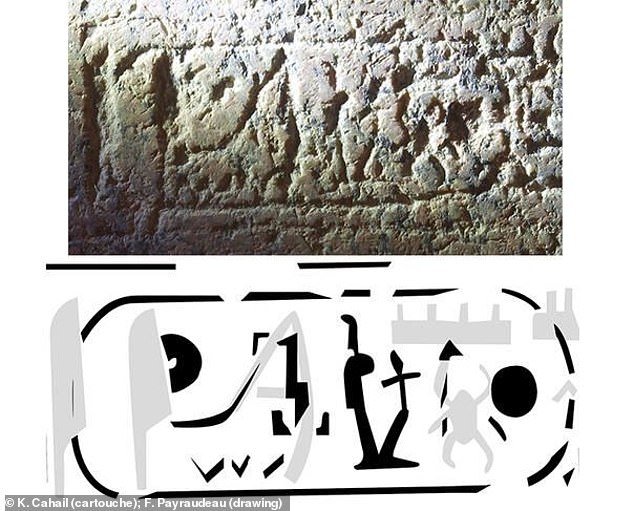

Egyptologist Frédéric Payraudeau, a lecturer and researcher at Sorbonne University in France, made the discovery this month after revisiting a fragment of granite discovered in Abydos in 2009.

He determined that the stone, which was one and a half meters long and eight centimeters thick, contained an overlooked engraving that read “of Ramses II himself,” according to a translated text. rack from the French National Center for Scientific Research.

‘When I read these results, I was overcome with doubt. “I asked my American colleague if I could re-examine the file, which he accepted given the complexity of this case,” Payraudeau said.

‘My colleagues believed that the cartouche, preceded by the word ‘king’, designated the high priest Menkheperre who ruled southern Egypt around 1000 BC.

‘However, this cartridge actually predated the previous engraving, thus indicating its first owner.’

He further explained that carvings of the Book of Doors, an initiation story reserved for kings during the time of the Ramses, were also seen on the sarcophagus.

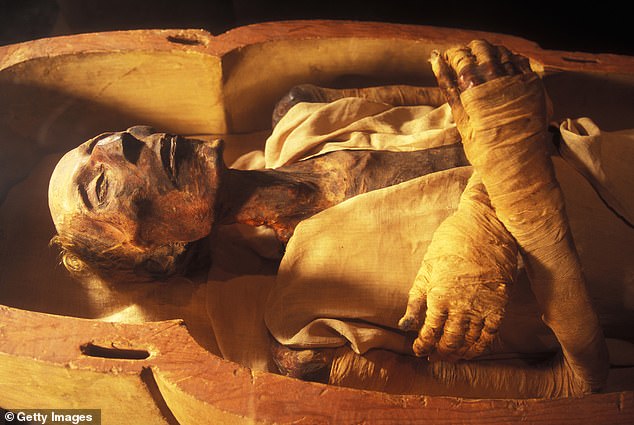

The mummy of Ramesses II was first discovered in 1818, along with the other royal mummies in the shelter of Deir el Bahari

The overlooked carvings revealed Ramesses II’s coronation name, but were masked by the condition of the stone. Researchers have made a drawing of the original engravings

“The royal cartouche contains the coronation name of Ramesses II, which is specific to him, but this was masked by the condition of the stone and by a second engraving, added during the reuse,” Payraudeau said.

Archaeologists have long known that Ramesses II was buried in a gold coffin, stolen in ancient times, and moved to an alabaster sarcophagus that was later destroyed.

The thousands of pieces were placed in the large granite sarcophagus that was stolen by Menkheperrê 200 years later for reuse.

“This discovery is further evidence that the Valley of the Kings was at that time the subject not only of plunder, but also of the reuse of funerary objects by later monarchs,” Payraudeau said.

Ramses II was the most powerful and celebrated ruler of ancient Egypt.

Known to his successors as the ‘Great Ancestor’, he led several military expeditions and expanded the Egyptian empire from Syria in the east to Nubia in the south.

During his reign from 1279 to 1213 BC, called Ramesses the Great, colossal statues and buildings were erected in what is marked as the final pinnacle of Egyptian imperial power.

Ramesses II is known for building colossal statues of himself

He was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt.

Scientists from Egypt and England have recreated the face of Ramses II in 2022 using a 3D model of his skull to rebuild his facial features.

They then reversed the aging process, turning back the clock nearly half a century to reveal his face at the height of his powers.

The result is the first ‘scientific facial reconstruction’ of the pharaoh based on a CT scan of his skull.

Sahar Saleem of Cairo University, who made the 3D model of the skull, said the outcome had produced a “very nice” ruler.

“My imagination of Ramses II’s face was influenced by his mother’s face,” Saleem said.

‘However, the facial reconstruction has helped give the mummy a living face.

‘I think the reconstructed face is a very handsome Egyptian, with facial features characteristic of Ramses II: the pronounced nose and the strong jaw.’

Scientists from Egypt and England have recreated the face of Ramesses II in 2022 using a 3D model of his skull to rebuild his facial features

Sahar Saleem of Cairo University, who made the 3D model of the skull, said the outcome had revealed a ‘very handsome’ ruler

Caroline Wilkinson, director of the Face Lab at Liverpool John Moores University, which rebuilt the pharaoh’s face, described the scientific process.

She said: ‘We take the computed tomography (CT) model of the skull, which gives us the 3D shape of the skull that we can incorporate into our computer system.

‘Then we have a database with pre-modeled facial anatomy that we import and then adapt to the skull.

“So we’re actually building the face, from the surface of the skull to the surface of the face, through the muscle structure and the fat layers, and finally the skin layer.”

She continued: ‘We all have more or less the same muscles from the same origin with the same attachments.

‘Because each of us has slightly different proportions and shapes of our skulls, you get slightly different shapes and proportions for the muscles, and that directly affects the shape of a face.’

The project is the second of its kind that Sahar recently oversaw, following a scientific reconstruction of Tutankhamun’s face completed by royal sculptor Christian Corbet.

For the professor, the process helps restore the mummies’ humanity.

She said: “Placing a face on the King’s mummy will humanise him, create a bond and restore his legacy.

‘King Ramesses II was a great warrior who ruled Egypt for 66 years and initiated the world’s first treaty.