Egyptians got backaches too! Ancient writers suffered from skeletal problems from sitting for too long, research shows, just like today’s office workers

Most of us have experienced the feeling of a bad back after sitting hunched over a desk for too long.

Now it turns out that the ancient Egyptians were exactly the same.

A study shows that repetitive tasks performed by ancient Egyptian scribes – men of high status with the ability to write who performed administrative tasks – and the positions they sat in while working may have led to degenerative changes in the skeleton.

Researchers in Prague, Czech Republic, examined the skeletal remains of 69 adult males, 30 of whom were scribes, who were buried between 2700 and 2180 BC in the necropolis of Abusir, Egypt.

They identified degenerative joint changes that were more common in scribes than in men in other professions.

Egyptian scribes were men of high status and the ability to write, who performed administrative tasks. Depicted is a statue of a high-ranking scribe

Most of us have suffered from a sore back after sitting hunched over at a desk for too long. Now it turns out that the ancient Egyptians were the same way (photo from the archive)

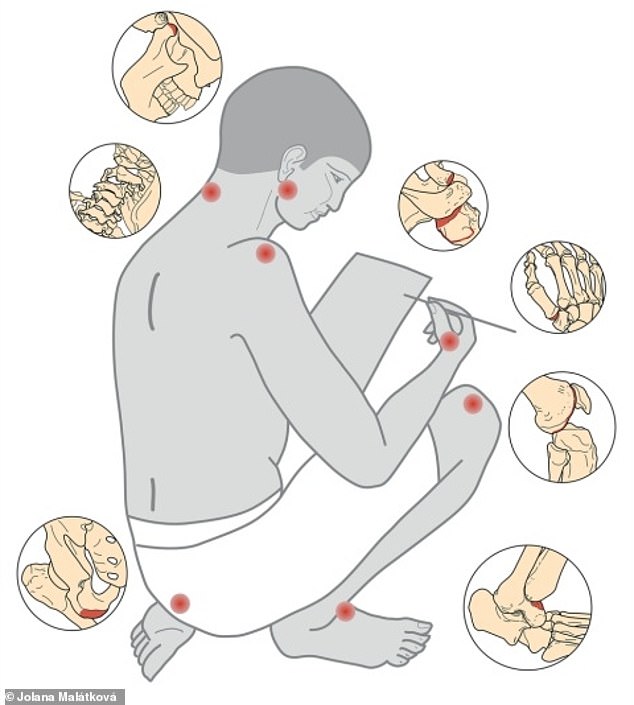

These changes occurred in the joints connecting the lower jaw to the skull, the right collarbone, and the top of the right humerus (where it attaches to the shoulder).

They were also located at the first metacarpal of the right thumb, the bottom of the thigh (where it meets the knee), and throughout the spine, but especially at the top.

Other skeletal features more commonly found among scribes included a notch on both kneecaps and a flattened surface on a bone in the lower part of the right ankle.

The authors suggest that the degenerative changes observed in the spine and shoulders of writers may result from prolonged sitting with legs crossed, head bent forward, spine flexed, and arms unsupported.

Repetitive tasks performed by Egyptian scribes (high-status men who could write and perform administrative tasks) and the positions they held while working may have led to degenerative skeletal changes, experts say. Pictured are statues of high dignitary Nefer, a scribe, and his wife in Abusir, Egypt

This drawing by an ancient Egyptian writer shows the most affected parts of the skeleton

However, changes in the knees, hips, and ankles may indicate that writers preferred to sit with the left leg kneeling or cross-legged and the right leg bent with the knee pointing upward (in a crouched or crouched position).

The team of authors, led by experts from the Anthropology Department of the National Museum in Prague, notes that statues and wall decorations in tombs have depicted scribes sitting in both positions, as well as standing, while working.

Degeneration of the jaw joints may have resulted from chewing the ends of rush stems to form brush-like heads with which they could write, while degeneration of the right thumb may have been caused by repeatedly squeezing their pens.

The findings provide further insight into the lives of writers in ancient Egypt in the third millennium BC.

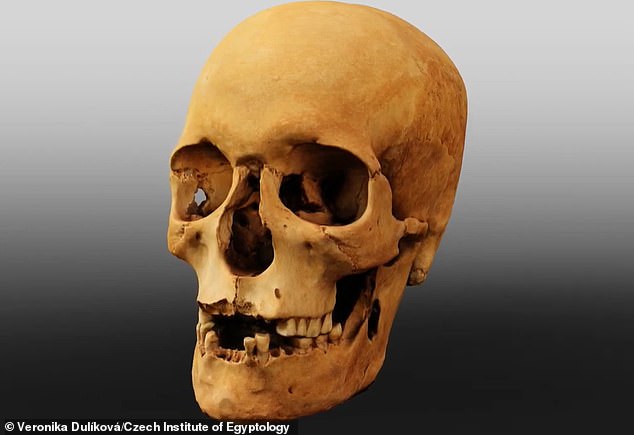

Model of the skull of Nefer – the ‘overseer of the crew scribes’ and ‘overseer of the scribes of royal documents’

The authors write in Scientific reports: ‘Men with writing skills enjoyed a privileged position in ancient Egyptian society.

‘Research focusing on these officials of high social status (“scribes”) tends to focus on their titles, script images, iconography, etc., but the individuals themselves and their skeletal remains have been neglected.

‘Statistically significant differences between the authors and the reference group indicated a higher incidence of changes in the authors and manifested itself mainly in the occurrence of osteoarthritis of the joints.

Our research shows that sitting cross-legged or kneeling for long periods of time, and the repetitive tasks of writing and adjusting the styluses while writing, puts extreme strain on the jaw, neck and shoulder regions.