Dustborn offers perspective on the choices that shape us

One of the first tutorial messages that appear on the screen in Dustborn is a warning that what you say in conversations will affect your relationships with other characters, but that there is “no wrong answer” to choosing. Introduced as a story-driven experience shaped by your choices, Dustborn riffs on the Telltale-esque formula by making everyone remember your actions. However, it takes the concept a step further, as your actions also affect how you and other characters develop over time. Developed by Red Thread Games and published by Spotlight, Quantic Dream’s publisher, the result is an ambitious story that often gets bogged down in its aspirations, but does so without ever abandoning its heartfelt nature.

The road trip story begins with a group of four 30-somethings in a minivan, escaping after a robbery. The mission is to travel across an alternate version of the United States to ultimately deliver their stolen package to Nova Scotia, Canada. Your biggest obstacle is evading surveillance from Justice, a fascist regime primarily interested in persecuting Anomals, people who can speak certain words to summon special powers after a mysterious event that occurred decades ago. As you’ve probably guessed by now, all four people in the van are Anomals, including protagonist Pax.

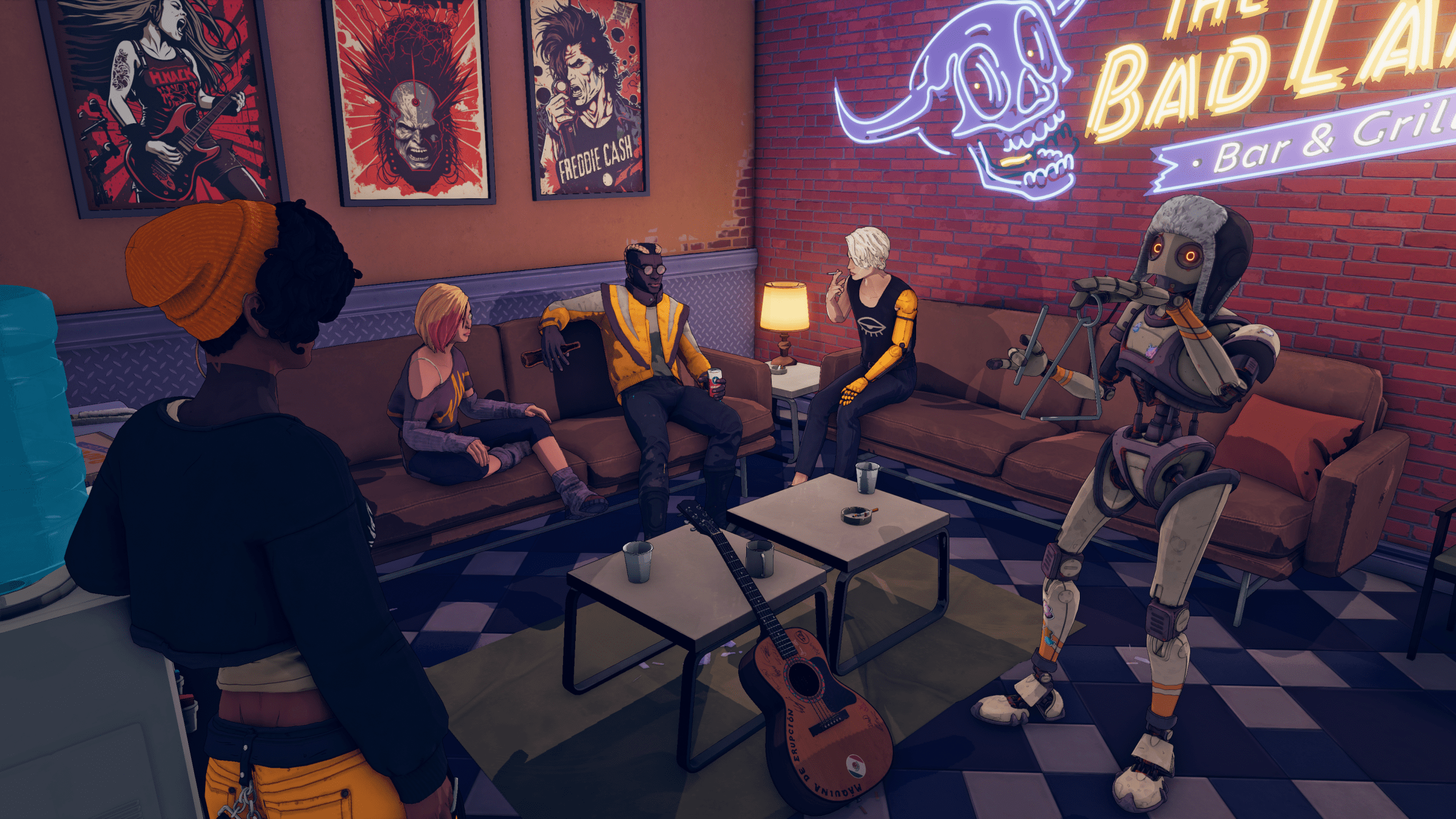

In order to reach Nova Scotia undetected, the group’s cover is to pose as a punk rock band, despite their lackluster musical skills. The road trip is dictated by performances, using fake IDs and forged work permits, which you play out in a standard Guitar Hero-style minigame. When you’re not on stage, you’ll stop at various locations to make contact with members of a resistance group, rest at campsites to rehearse and catch up with characters, or compose new songs.

During the 20 hours it took me to see the credits, Dustborn‘s story took a dozen different turns. At first I expected it to unfold in a similar way to Life is strangein which people with supernatural powers are shown in largely grounded descriptions of our reality. Dustborn follows this to some extent, but ultimately prefers fiction more often.

This alternate America is dictated by the assassination of JFK, which was instead Jackie Kennedy, and the various events that followed, including the rise of the Anomals. The game is set in 2030, with an already established robot presence and a pervasive commentary about how reliance on them sucks (a robot goes berserk and steals your vehicle, server issues nearly kill a mechanic pinned under a bus, and so on).

With each new location you visit, the world and its inner turmoil continue to expand. Justice isn’t the only enemy; there’s also the Puritans, a group of technology-obsessed zealots from whom you stole the package, and another entity that shows up in the latter half of the story. The game’s story also delves into the origins of the Anomals – with lengthy expositions of language that feel like listening to Skullface in Metal Gear Solid 5: The Phantom Pain — plus flashbacks to Pax’s childhood, her past relationships with some of the crew, battle sequences, and much more in spoiler territory. The story is always trying to cast a wider net, and in the process, some threads end up underdeveloped at best and forced at worst.

One part of the game that works is the emphasis on different points of view. It doesn’t matter who you talk to in Dustbornyou are free to choose the camera’s perspective. Each conversation starts with a default angle, but you can move the camera around the scene, following an invisible path until it stops somewhere else, creating a different point of view.

Sometimes the camera might start on a bench with two characters having an intimate conversation while the rest of the group is gathered around a campfire in the background. Then pan the camera, and the scene cuts to just the two of them staring out into the moonlight on the ocean. During a tense moment in the story, the camera angle might provide an opportunity to rebuild trust in a group that has been shattered by betrayal, with everyone in the frame. Or it might change to emphasize that fracture, isolating the perpetrator to one side of the screen while the others listen to him plead his case.

At the heart of it all is the characters writing and their specific vocal powers (called Vox) that kept me engaged. From the start it was refreshing to see such a diverse cast that largely ignores media stereotypes and features characters who are allowed to be angry, messy and happy in their own way.

While I cannot speak with authority on the backgrounds of each of the characters depicted in this book, DustbornI was especially surprised by Theo. Since he’s a Mexican character, I was fully prepared to hear constant Spanish jokes à la Jackie Wells in Cyberpunk2077 or the characters in Far Cry 6Spanglish is of course not uncommon, but as a colleague Latin Americanit was satisfying to see Theo follow the rule of thumb: When you’re surrounded by English speakers, you have to stick to English to be understood. Only during moments of surprise would Theo let out a Spanish sentence, until a later scene where he calls a family member. Seen from Pax’s perspective, if you choose to eavesdrop, the subtitles show the conversation in Spanish, while Pax’s thought bubbles “translate” the key parts. I’m glad I didn’t have another “(ominous muttering in Spanish)” subtitles.

The development team’s care for each character is palpable, and talking to them at every opportunity I had became a necessity after seeing how their personality archetypes could be shaped by different actions and conversations. Theo, for example, can either stick to his role as group leader or slowly open up and become more a part of the team, with the lack of impartiality that comes with it. This feature isn’t perfect, though: while your actions carry weight, some of the default storylines feel intrusive, and not always in the best way.

In one instance, a character left the group after a tirade, even though we’d had a conversation the night before about how much their relationship with Pax had improved. More often than not, I was forced to use Pax’s Vox with the crew, such as bullying them or temporarily blocking them from speaking, despite the clear consensus among the characters that doing so was invasive. These moments didn’t completely cloud my sense of player agency—stories need structure, after all—but they did take away the weight of some of my earlier actions.

There are ways in which Dustborn challenges its own conventions, such as letting other characters use Vox with Pax without any way to prevent it. What stood out to me the most was the existence of time-limited dialogue options. The more you listen to certain conversations, the more options appear over time, while older ones expire. It made me think about the importance of knowing when to interrupt someone, and when it’s time to just keep your mouth shut and listen to the other person without saying a word, allowing them to vent their frustrations after a stressful event.

There’s a conversation with the group about halfway through the story where you’re told how often you’ve actually listened to someone and the impact of your seemingly small actions. After all, small actions can change the way scenes unfold. It was funny to see the characters’ dinner get a little burnt because I helped the robot in charge choose a hat while they were trying to figure out their identity. I managed to reestablish Pax’s connection with a family member, but ultimately they leaned into their idealistic archetype and followed their own path. I chose to support this decision, even though I knew they would eventually part ways with Pax, and it felt good to have that option available.

The biggest culmination of your decisions comes at the very end, when you don’t have a “select your ending” prompt. Instead, a message appears on screen telling you that your choices and actions all along have determined how the story would end. You get to watch Pax’s decision unfold without your input, and who decides to stick with her for whatever comes next.

As much as Dustborn leans on its science fiction setting, the story is told from a point of view that shows clear parallels to reality. There are nods to jokes like “my husband and i saw you from across the bar” and also mentions of “woke mind virus” speeches and how downright stupid they are. One of Pax’s Vox even allows her to “cancel” someone — which is a bit obvious, given the contrast between Dustborn‘s queer and BIPOC characters against Quantic Dream’s alleged misogynistic and homophobic responses to a lawsuit alleging the studio was a toxic workplace.

As a whole, Dustborn is as messy and imperfect as the characters you meet. The storylines can be intrusive and there are multiple unresolved threads. But it makes sense not to have an influence on everything, to have a limited influence on the people around you. Dustborn is a reminder of how seemingly innocent gestures may not always have a tangible impact, but they always shape who we are and how we relate to others. In a game driven by decisions, the most satisfying choices weren’t about getting the right answer — they were about gaining a different perspective.

Dustborn was released on August 20 on PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, Windows, Xbox One, and Xbox Series X. The game was reviewed on PlayStation 5 using a pre-release download code provided by Spotlight by Quantic Dream. Vox Media has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though Vox Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. You can find additional information about Polygon’s ethics policy here.