Doomsday Clock will be updated next week to determine our fate

>

It has tracked the probability of humanity’s annihilation for over 75 years.

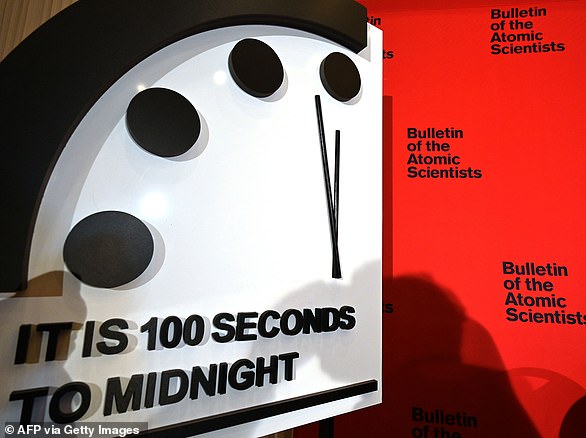

And next week, the Doomsday Clock will update once more to determine our fate, having stayed at 100 seconds to midnight for the last three years.

With Russia’s war on Ukraine, weather disasters raging around the world, and the coronavirus still lingering, it’s hard to imagine the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists going back in time.

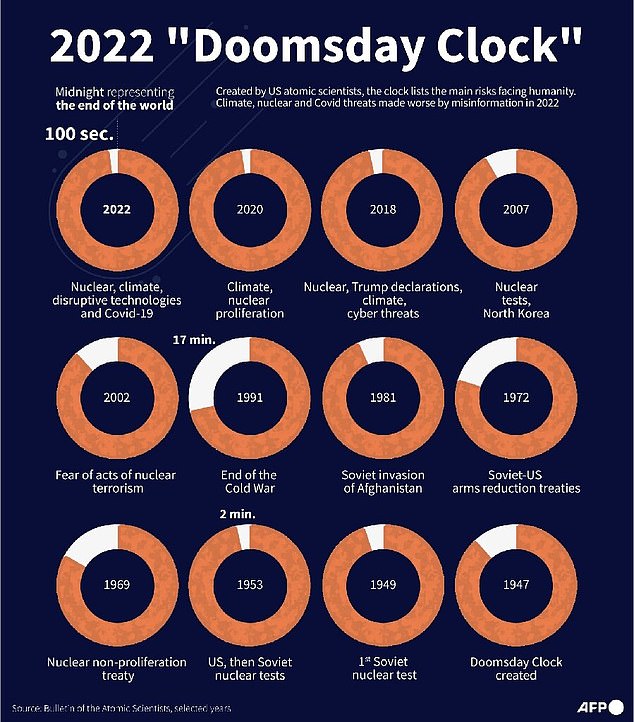

The clock, an idea that began in 1947 to warn humanity of the dangers of nuclear war, was originally set at seven minutes to midnight and has since moved back and forth 24 times.

On the Verge: Next week, the Doomsday Clock will update once more to determine our fate. It was founded by American scientists involved in the Manhattan Project, which led to the first nuclear weapons during World War II, and is a symbolic countdown to represent how close humanity is to completing global catastrophe. In the photo, the first inauguration in 1947.

Presentation: Last year, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists announced that the clock would stand at 100 seconds to midnight for the third consecutive year (pictured)

In 2020 it reached the closest to midnight and has stayed there for the last three years.

At the height of the Cold War in 1953 it was two minutes away, and the farthest it has gotten from midnight was when it moved to 17 minutes earlier at the end of the same war.

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists will announce if the symbolic clock time will change to 15:00 GMT (10:00 ET) on January 24.

He describes the watch as a “metaphor for how close humanity is to self-annihilation.”

By 2023, the Bulletin said it would take into account the Russia-Ukraine war, biological threats, the proliferation of nuclear weapons, the ongoing climate crisis, state-sponsored disinformation campaigns, and disruptive technologies.

The decision will be made by the Bulletin’s science and safety board and its board of patrons, which includes 11 Nobel laureates.

The organization was founded in 1945 by Albert Einstein, J Robert Oppenheimer, and other scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project, which produced the first nuclear weapons during World War II.

By 2023, the Bulletin said it would take into account the Russia-Ukraine war, biological threats, the proliferation of nuclear weapons, the ongoing climate crisis, state-sponsored disinformation campaigns, and disruptive technologies.

With Russia’s war on Ukraine, weather disasters raging around the world, and the coronavirus still lingering, it’s hard to imagine the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists going back in time. In the photo: Ukrainian servicemen stand on their tanks in Bakhmut, Donetsk region, on January 13.

The idea for the clock followed two years later as a symbolic countdown to represent how close humanity is to completing the global catastrophe.

Artist Martyl Langsdorf was commissioned to make the clock and told to create an image that would “frighten men into rationality,” according to Eugene Rabinowitch, the first editor of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, who died in 1973.

Langsdorf developed a simplified watch to reflect urgency and only the last quarter hours before midnight are displayed on the dial.

It was also his decision to set the minute hand to seven minutes before midnight, which was only meant to be visual, before Rabinowitch moved it to three minutes in 1949.

“For 75 years, the Doomsday Clock has acted as a metaphor for how close humanity is to self-annihilation,” reads the website of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists.

“Since 1947, it has also served as a call to action for reversing hands, which have been moved backwards before.”

The Doomsday clock was first moved to 100 seconds to midnight in January 2020 and remained there in 2021, in part due to a “lack of action” over the Covid pandemic.

Since 1947, it has been delayed eight times and advanced 16 times.

The time is determined taking into consideration all the events that have happened throughout the year.

It can include politics, energy, weapons, diplomacy, and climate science, along with potential sources of threats such as nuclear bombs, climate change, bioterrorism, and artificial intelligence.