Don’t say the A-word, says Sainsbury boss as he earns £220m in battle with Aldi

The struggle families face to pay their bills has left Britain’s biggest supermarkets in an identity crisis. Budget chains Aldi and Lidl have moved to the higher market. They have convinced affluent households that quality has improved and that the majority of their customers are now middle class.

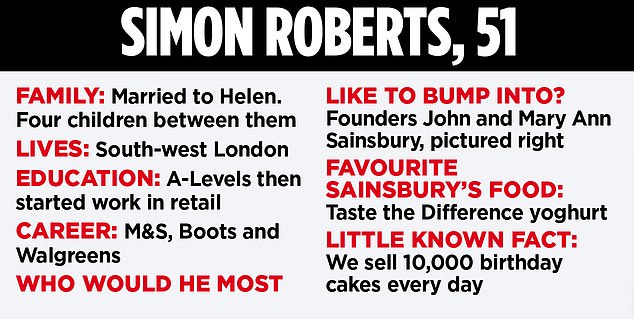

The question for Sainsbury’s CEO Simon Roberts is whether he can achieve a similar effect, only in reverse.

Sainsbury’s has always been seen as a high-quality grocer, but can it convince skeptical shoppers that its stores, which have a reputation for being posh and pricey, really offer value for money these days?

Roberts, 51, has been an evangelist by this point since taking the top job in 2020. He put his foot on the gas this month with a major price-match promotion. More than 550 items are compared with the German discount store Aldi, including more than 60 baby products.

Roberts seems a little obsessed with Aldi. Why does he compare Sainsbury’s to them all the time? “We compare everyone,” he says, though the “A word” comes up a lot.

Courting the Middle Class: Simon Roberts skipped college and worked his way up from the workplace

During the financial year to March, Sainsbury’s will have invested £220 million in cutting costs for its customers. This also includes the ‘nectar prizes’, which provide large discounts to cardholders, partly financed by suppliers, who make an additional contribution.

Roberts – who skipped college and worked his way up from the shop floor – took on the top job at a difficult time.

His predecessor, Mike Coupe, had tried to push through a merger with Asda, which was thwarted by competition watchdogs. The failure of that deal left Sainsbury’s forced to build a future against cut-throat competition from Aldi, Lidl and Tesco.

Then came Covid, followed by supply chain bottlenecks, rampant energy prices and a cost of living crisis with runaway food inflation.

Roberts’ big idea was to get back to basics with a strategy he calls “Food First.” This means that all income – from any part of the Sainsbury’s empire, including Argos, the petrol stations, Tu clothing and Habitat – will be reinvested into the food industry.

An update on the next phase of the strategy is scheduled for February 7, but there have been changes to the operating board in the lead-up. And last week Roberts revealed that Sainsbury’s Bank was up for sale after 27 years.

He declines to be drawn further into the looming question of strategy, and whether other non-food companies are under scrutiny, but says: “We have really started to shift the profitability of our business.

‘This year we will have revenues of somewhere between £670 million and £700 million. Three years ago it was less than £600 million. Before Covid it was £586 million.

‘We have saved £1.3 billion in costs. We have had to make some difficult decisions. We decided to stop running counters (for cheese, fish and delicatessen), we decided to take our standalone Argos stores into the supermarkets, we reduced the number of office locations and consolidated them.

‘We went after everything that wasn’t about serving customers better. It was a matter of saving to invest.’

A total of £780 million has been spent on cutting prices since the launch of the Food First strategy.

The chain is also spending £200m on a 9 per cent pay rise for 120,000 hourly staff. Their rate will rise to £13.15 per hour in London and £12 per hour elsewhere.

Roberts said: ‘By investing in keeping food prices low and investing in our staff, we deliver a better service, which means better returns for shareholders.

‘It’s a virtuous circle and we’re going to accelerate. This is a big moment for us to really push forward.

‘Three years ago we recognized a fundamental problem. Customers wanted to shop at Sainsbury’s, but we were too expensive. The Food First strategy was about tackling that. Until you get the right value, nothing else will work.”

To drive home the message, Sainsbury’s has launched a new advertising campaign. Starring Kevin McCloud, the presenter of the Channel 4 program Grand Designs, which is notorious for its lavish construction projects with spending spiraling out of control. McCloud makes a cameo appearance at the box office, saying incredulously, “We stayed on budget.”

I meet Roberts in one of the many kitchens at the company’s headquarters in Holborn, central London, where new recipes are created and tested.

Claire Hughes, director of product development and innovation, explains that Sainsbury’s introduces around 1,400 new products every year. Salted caramel, she says, is a perennial favorite, along with sticky toffee flavors, including a rum liqueur. She and her team took a trip to the US and returned with inspiration for hickory-smoked American barbecue flavors.

Roberts waves slides showing how the company outperformed Tesco, Morrisons and Asda in the run-up to Christmas. Food inflation, he says, “was a very big challenge last year.” It has fallen sharply from a peak of 19.2 percent in March, but was still at 8 percent last month. He rejects the suggestion that there is an element of ‘greedflation’: raising prices under the cover of inflation to boost profits.

Roberts insists Sainsbury’s customers have never seen inflation in their weekly shop as high as official figures suggest, as they switched to cheaper options and reduced food waste.

His approach may work for customers, but what about investors? The shares are up 17 percent in the past twelve months. However, they have been on a rollercoaster trajectory over the past five years and are barely higher than they were in 2019.

At the top of the investor register is the Qatar Investment Authority with a 14 percent stake, followed by Czech tycoon Daniel Kretinsky’s Vesa Equity Investment with just under 10 percent.

I suggest it’s all very well to talk about lower prices in stores and higher wages for staff, but don’t shareholders like these want a bigger slice of the pie?

“Looking at dividends for shareholders is part of that system, but that’s not where you start,” says Roberts. In 2019 and 2020 we were too expensive for customers and shareholders wanted better returns. How were we going to solve that? We have grown our profits over the past four years. We’ve done this by putting value for money and putting our customers first, looking after our staff and supporting the UK food system. Shareholders want sustainable returns.’

Asda was bought by private equity firm TDR Capital and the billionaire Issa brothers after the failed merger attempt with Sainsbury’s. As a result, the country has a huge debt pile of £4.2 billion. Morrisons was also taken over by private equity and loaded with debt.

“We have virtually no debt,” Roberts says. ‘You need the agility to make choices and prioritize investments in what customers find important.’ Translated, I think this means that if a supermarket chain is struggling with debt and has to pay high interest charges, it will not have as much flexibility to lower prices.

Roberts says: “When I took over as CEO we had quite a bit of debt. Our finance team has done a fantastic job working with us to reduce our debt.”

He monitors supply chain problems caused by attacks on ships near the Red Sea, which could impact goods such as electronics, wine and clothing.

‘Most shipping companies sail around Africa, which takes ten days or more, so it is more expensive. We are taking measures to prevent costs from passing on to customers.’

He adds: “The pandemic and the Suez Canal blockage have allowed us to develop many new capabilities.”

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on it, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow a commercial relationship to compromise our editorial independence.