Shocking letters reveal Don Bradman’s shattering confession about the last stages of his life – and his very surprising stance on stars who broke apartheid bans

Don Bradman’s strong belief that rebel Aussie cricketers were right to take huge sums of money to play in South Africa during apartheid has been revealed in a series of letters that also expose the grief the sporting icon felt in recent years of his life.

More than twenty letters that The Don wrote to a friend in England between 1984 and 1998 have been unearthed in the National Library of Australia.

The correspondence provides valuable insight into what the Australian thought about a range of the biggest issues facing the game – including the fact that he felt it was hypocritical for Australia to condemn stars for touring racially divided South Africa at a time when the federal government traded freely. with the country.

One of the biggest issues affecting cricket was apartheid in South Africa, which Bradman had very strong views on.

Apartheid was a system of institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination introduced in South Africa between 1948 and 1994.

It enforced strict racial divisions, denied basic rights and freedoms to the black majority and privileged the white minority.

The great Donald Bradman believed that Australian cricketers were right when they took large sums of money to go on rebel trips to South Africa

Rebel trips to South Africa were met with fierce opposition, as former England skipper Mike Gatting (centre) discovered during this 1989 protest

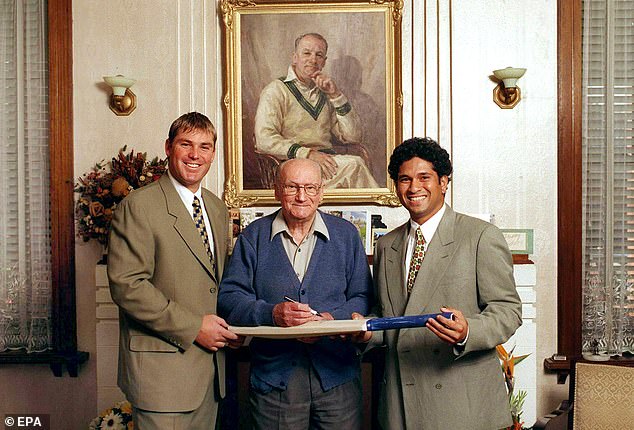

Bradman, pictured with Shane Warne and Sachin Tendulkar, canceled an Australian tour of South Africa while chairman of the Australian Cricket Board in 1970

This oppressive regime came to an end through domestic resistance and international pressure, leading to democratic elections and the leadership of Nelson Mandela in 1994.

Apartheid led to South Africa’s exclusion from international sports, including a ban from the International Cricket Council in 1970, with South Africa only rejoining international cricket in 1991 after the system began to dismantle.

Many countries refused to compete with South Africa, and rebel tours by foreign players that defied the boycott drew global criticism.

Bradman was involved in efforts to boycott South Africa in the 1960s and 1970s in response to the country’s apartheid policies:

As chairman of the Australian Cricket Board, Bradman canceled the 1970–71 South African cricket tour of Australia.

He also stated that there would be no more cricket tours involving South Africa until their teams were chosen on a non-racial basis.

However, stars Kim Hughes, Terry Jenner and Graham Yallop were part of a squad of 14 leading Australian players who nevertheless took part in these unofficial tours in the 1980s, lured by significant financial incentives.

Bradman’s views on apartheid and rebel travel were revealed in a series of letters he wrote to a friend in England

These tours were widely condemned, with participants facing bans from official cricket and criticism for undermining the global stance against apartheid.

The timing also clashed with World Series Cricket, the formation of Kerry Packer in 1977 which would pave the way for ODI cricket by introducing night matches, colored uniforms and improved player rewards.

Bradman wrote that he feared the Rebels’ tours would lead to another Packer-led breakout competition, and that he feared the “black” nations would never lead South Africa back into world competition.

“Since I last wrote, the cricket world has been in a ferment,” he wrote.

‘What with players signing for England and South Africa and Packer signing players individually, God knows where it will end up.

‘I don’t blame the players. One I know has been out of work for two years and is going to a fair [sic] $200,000 for two years was too good to turn down.

‘Of course the whole thing depends on dirty, rotten politics.

“Our government trades freely with South Africa and it is total hypocrisy for them to prevent sporting contacts.

“The ‘black’ countries will never agree to readmit South Africa and the ultimate answer will be total division between blacks and whites.”

However, Kerry Packer’s breakout league never materialized and South Africa was eventually readmitted to world cricket, but as a result of economic policy, not because of any seismic action from the sport.

Nelson Mandela would later describe Bradman as his ‘ultimate hero’ for his stand against apartheid.

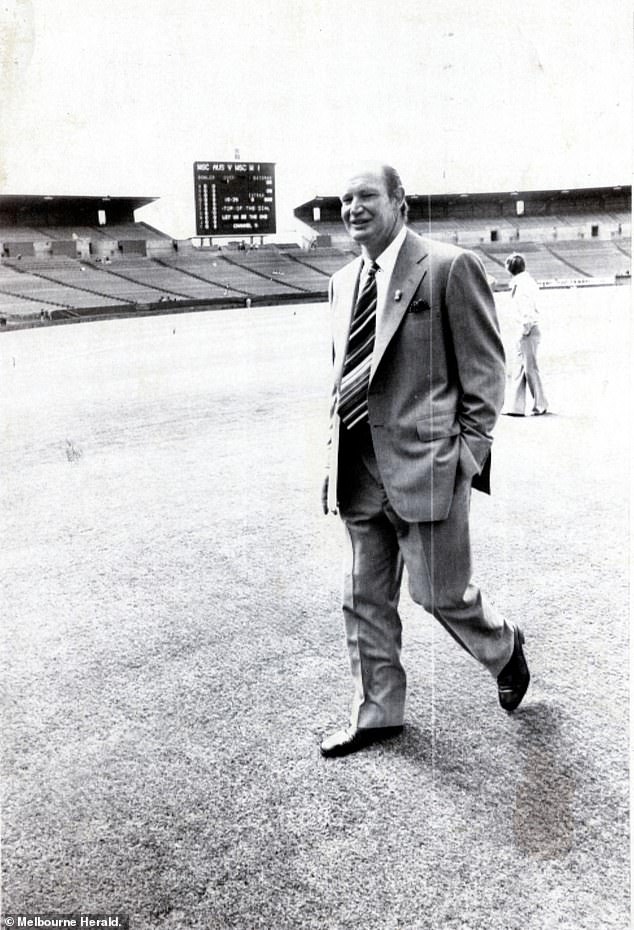

Bradman feared apartheid would tear the cricket world apart – and he harbored similar fears about the one-day revolution started by Kerry Packer (pictured)

Nelson Mandela was a great admirer of Bradman for his stand against the horrific racial discrimination in South Africa

“Mandela loved Bradman because of his stance on racism. Perhaps more than anyone else,” wrote biographer and close friend of Bradman Roland Perry.

Unfortunately, due to Bradman’s frailty in his older years, he never met Mandela.

Sadly, Bradman also wrote in his letters about his loneliness in his final years before he died in 2001.

Bradman’s wife Jessie Menzies died in 1997, while many of his teammates also preceded him.

Vice-captain Lindsay Hassett died in 1993, Sid Barnes tragically took his own life in 1973 aged just 57 and fast bowler Ray Lindwall died in 1996.

‘I’m struggling to get on with life, but wherever I go there is sadness and memories. Even after a game of golf or bridge there is no one to talk to and as you rightly said the nights are so empty,” Bradman wrote.

However, Neil Harvey is still alive, at the age of 96, and has spoken of the guilt he felt at costing Bradman the chance to end his career with a batting average of over 100.

Harvey had hit a four to win the match in Bradman’s penultimate Test against England. If Bradman had scored those points, he would have maintained his 100 average.

‘I’m willing to take the blame. But little did I know he would get a duck in his last Test match… Nobody knew Bradman needed four runs at Leeds; no one knew he needed four runs when he played in his last Test at the Oval,” Harvey said in 2018.

‘Statistics were never talked about then; there was no television and no one in the press seemed to know. When the poor guy got bowled, that was it. He wouldn’t get another chance because we dismissed England for 52 in their first innings.’