Documents show how two black World War II soldiers were killed by a white colleague

>

A pair of black soldiers who served in World War II have been killed by a superior white officer for challenging segregation and speaking to female Red Cross workers at a camp in France, newly discovered documents have revealed.

The slain soldiers, Allen Leftridge and Frank Glenn, were challenged by the sergeant for breaking the rules, archived documents show, and then mercilessly shot dead by another officer as punishment.

Despite the illegality of the action and the fact that several witnesses saw the killings firsthand, the killer, an unidentified US soldier, was acquitted and the widow of one of the men was denied a survivor’s pension.

The altercation also saw a third soldier, a white man recently released from a German prison camp, killed in the crossfire, the two white soldiers involved in the killings, which took place on the war-torn Western Front in 1945, acquitted of their actions. .

Once long forgotten, the duo’s story is now told thanks in part to that woman, the late Sarah Leftridge, who shared the harrowing tale with a black journalist who would eventually marry her.

Previously forgotten, the story of Allen Leftridge and the other slain soldier is told thanks to his late widow Sarah Leftridge, who gave a harrowing account of the incident, after being told by army officials that her husband’s death “was due to his own death.” bad behavior’

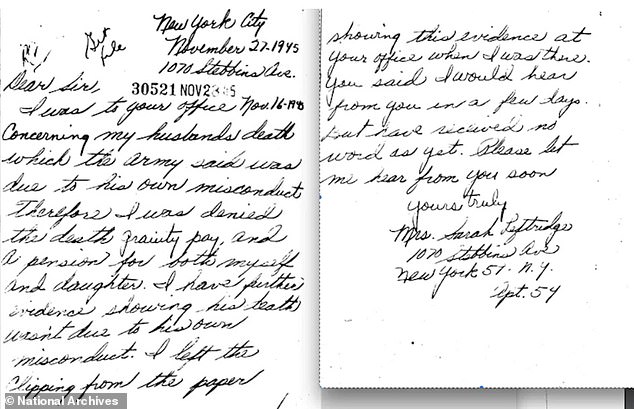

The newly opened documents containing letters offer her own account of the incident, in which she was told by army officers that her husband’s death was due to “her own misconduct.”

Nearly a century later, the couple’s descendants are seeking justice after, for reasons unclear, the widow was denied her due military benefits.

That ruling came from a US judge who ruled in a court martial convened after the 1945 incident that her husband’s death occurred after he ignored his superiors.

The incident occurred towards the end of the long-running conflict at an allied encampment known as The Lucky Strike, according to eyewitness accounts and unsealed Army documents.

The camp was a bustling tent city with approximately 58,000 American soldiers at the time awaiting transportation back to the United States after victory in Europe.

That said, the settlement was also heavily segregated, being described as “seventh heaven” and a center of riotous chaos due to rising tensions among war-weary troops.

The incident occurred towards the end of the long-running conflict at an Allied encampment known as The Lucky Strike, a bustling tent city with an estimated 58,000 US soldiers who at the time were waiting to be transported back to the United States after victory in Europe. .

The meeting in question occurred at the height of these tensions approximately two weeks after the end of the war in September 1945.

Documents and witness accounts detail how Leftridge and Glenn, whose death, unlike his partner, was ruled a result of the line of duty and his widow was awarded compensation. he entered a Red Cross tent where the women served donuts and coffee to the soldiers.

The soldiers at some point went in to look for something, disobeying the laws established by the army that prohibited black soldiers from socializing with French women.

At the mass camp, black troops were typically tasked with protecting German prisoners, prompting officials to make the rules amid fears that black men would engage in interactions with white Europeans.

There are various accounts of what happened next, although the duo they were reprimanded by an anonymous officer, who Alfred A. Duckett, Stacy Leftridge’s second husband, said was romantically involved with one of the women.

‘[The] The white MP ordered him not to stand there talking to this woman, Allen turned his back on him,” Duckett said in an interview published in Studs Terkel’s 1984 oral history, “The Good War.”

Duckett, who died in 1984, was a journalist whose reporting thus far has served as the main account of the encounter.

Duckett described how a subsequent fight left Leftridge ‘shot in the back and killed’ by an armed guard called in to quell the encounter. Glenn was also killed at some point during the previously covered up incident.

There have been various accounts of the 1945 encounter, in which the duo were reprimanded by an anonymous officer who Alfred A. Duckett (right), Stacy Leftridge’s second husband, said was romantically involved with one of the women. Duckett, a journalist, learned of the story after meeting Stacy and her daughter (pictured) in 1950. The couple would marry soon after.

However, in an undated statement from the Library of Congress discovered by The Washington Post, a witness, Solomon Johnson, said Leftridge and the sergeant “got into a heated argument and suddenly came to blows” before his death and the from Glenn.

After the fight ended, the witness reportedly said, Leftridge ‘stepped’ towards the guard, who then shot him.

According to the documents, Johnson told Army officials investigating the incident that the unnamed guard, who was white, “never gave the command ‘to stop’ or gave any warning” to indicate he was about to shoot Leftridge, let alone against Glenn.

Although a court martial was called and the two unidentified white men were brought to trial, no legal action was taken in connection with the altercation, neither to the sergeant nor the guard, nor to their partner’s senior officers. .

In an explanation to the NAACP, the Army said Leftridge was killed because the soldier “disregarded” a challenge from a superior officer. Since then, the organization has accepted calls from Leftridge’s late widow to rectify the service record of her first husband.

The new documents shed new light on the decades-long altercation, revealing that nearly a century laterThe racial injustices committed against black servicemen during World War II are finally being addressed.

Duckett previously only referred to the case in the 1984 oral history, and Sarah’s efforts to obtain military benefits from the Army have yet to be successful.

The duo’s history was detailed by the late Sarah Leftridge in newly unsealed Library of Congress papers, which contain documents including this letter from Sarah to military officials asking that her husband’s record be rectified.

However, thanks to reports from her late husband, who became obsessed with the case after interviewing Sarah about the incident and eventually married her in 1950.

Leftridge’s daughter, Carolyn Holman, is now continuing her stepfather and mother’s efforts to rectify her late father’s legacy, continuing to call on Army officers to clear her name and compensate her family for back pay. which should have been sent to his mother.

With the recent attention the case has received, that appears to be a possibility, with an Army spokesperson hinting that action on the case could be taken in the coming months.

Madison Bonzo told the Post in a statement that the service “places a high priority on honoring the legacy of all of our soldiers and their families, especially when there may be a mistake or an injustice.”

“The Army stands ready to assist the Leftridge family through the Army Board for Correction of Military Records at the Army Review Boards Agency, should they decide to file a record correction request,” the Army said. release.