Doctors finally solve the mystery of the link between bacterial vaginosis and premature births in landmark study

- Researchers looked at human cells lining the vagina and found vital clues

- In BV, bacteria release enzymes that partially destroy protective molecules

- READ MORE: Sexual Health Doctor Reveals What You Should NEVER Do During Sex

Doctors think they have finally solved one of the most baffling medical problems that has long baffled women’s health experts.

Bacterial vaginosis – the most common vaginal infection – is known to be associated with an increased risk of serious complications during pregnancy and even sexually transmitted infections.

Suffering from the problem regularly – which happens when healthy vaginal bacteria grow out of control – is thought to double the risk of miscarriage, according to studies.

But until now, experts haven’t understood why.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is one of the most common vaginal conditions that, if left untreated, can lead to a higher risk of STDs and problems during pregnancy, such as miscarriage and premature birth.

Researchers at the University of California San Diego believe they have discovered how the bacteria disrupts the health of the vagina.

By looking at vaginal cells under a microscope, they saw that certain types of bacteria dismantle protective molecules on the surface of cells lining the genital tissue – called epithelial cells.

This disrupts vital processes that help damaged cells repair themselves, and disrupts the bacterial flora.

If the balance between healthy and unhealthy insects is not balanced, this can damage delicate internal tissue, which can ultimately lead to problems during pregnancy.

Study author Amanda Lewis, professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences at UC San Diego, said: ‘The fact that we were able to replicate some of the effects of bacterial vaginosis suggests that we may be on the right track to a common cellular origin for the various complications associated with this condition.’

Studying the surface of vaginal epithelial cells at this level of detail could make the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis easier, the researchers said.

They also suggest that looking for tell-tale changes in cells could also allow doctors to identify women at risk for complications such as preterm labor.

The findings were published in the journal Scientific translational medicine.

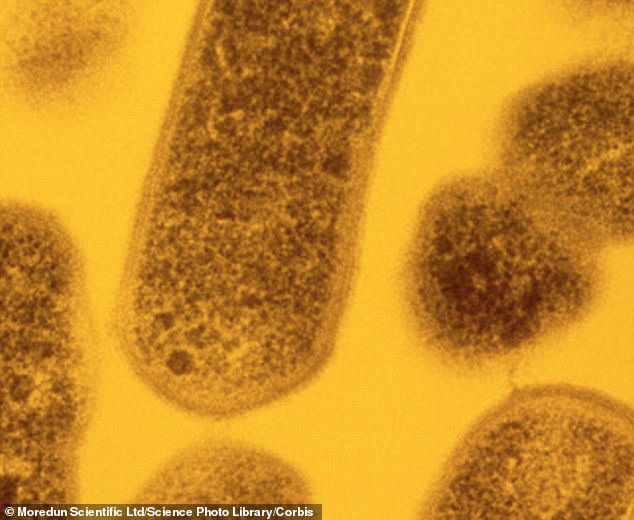

Bacterial vaginosis is a common condition in women – characterized by an imbalance between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ bacteria (such as Gardnerella vaginalis, pictured) normally found in the vagina

Callum Butler (pictured) was born after just 25 weeks of his mother’s pregnancy. His mother Amanda was later told that an infection she had called bacterial vaginosis was to blame. The condition can also cause miscarriage

Although BV is not an STD, it increases women’s risk of contracting a sexually transmitted infection.

This is because the infection erodes the vagina’s natural barrier, making it easier for germs to enter the body during sex.

BV, which affects about one in three women at some point in their lives, is caused by a change in the delicate bacterial balance in a woman’s vagina.

The most common symptom is a fishy-smelling discharge, especially after sex.

There may also be a change in the color or texture of the discharge, such as becoming gray or watery.

But half of women with BV experience no symptoms.

If a woman suspects she has BV, she should go to her doctor or sexual health clinic to confirm that it is not an STD.

Once diagnosed – via a ‘swab’ test with a cotton swab – BV is usually treated with prescription antibiotic tablets, or gels or creams.

Those who get it more than twice in six months need treatment for up to half a year.

BV can be prevented by using only water to wash the genital area and choosing showering over a bath.

Scented soaps, vaginal deodorants, douches, strong detergents and even smoking increase a woman’s risk for the condition.

BV is more common in people who are sexually active, have recently changed partners or have ‘the spiral’.

If BV is ‘contracted’ during pregnancy, it can lead to premature birth or miscarriage.