New DNA analysis of Pompeii victims reveals shocking truth about who they really were

New DNA evidence from bodies buried in Pompeii rewrites the stories about the people who lived there.

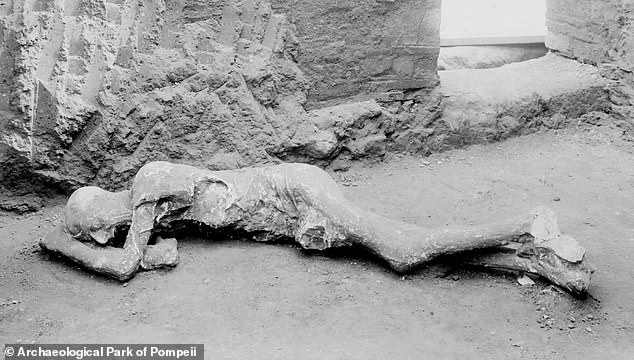

The volcanic eruption in 79 AD and the 20-foot-deep layer of sediment it released provided just the right conditions to trap dozens of bodies in their dying state.

Archaeologists used these impressions to create replicas of the victims and stories were told about those who died in more suggestive positions.

One of the better known plaster casts was of an adult holding a child in what appeared to be a loving embrace.

Known as the Two Virgins, it was previously believed to have been a mother who died with their daughter in their hands.

But the new analysis found that the larger body belonged to a man who was not genetically related to the child after all.

The team said their analysis clearly “debunked the narratives long spun around these individuals.”

Investigators discovered four Pompeian victims in a house where they were all believed to be part of one family. They initially thought two of the bodies were a woman with a child on her hip (pictured), but DNA testing revealed the adult was an unrelated man.

Alissa Mittnik from the Max Planck Institute said: ‘We were able to refute or question some of the previous stories based on the way these individuals were found in relation to each other.

“It opens up different interpretations of who these people might have been.”

Researchers also confirmed that Pompeii’s citizens came from diverse backgrounds, but were mainly descended from immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean – underscoring a broad pattern of movement and cultural exchange across the Roman Empire.

“Our findings have significant implications for the interpretation of archaeological data and the understanding of ancient societies,” Mittnik said.

‘They emphasize the importance of integrating genetic data with archaeological and historical information to avoid misinterpretations based on modern assumptions.’

Researchers focused on 14 casts that were restored, extracting DNA from the fragmented skeletal remains mixed with them.

They hoped to determine the gender, ancestry and genetic relationships between the victims.

Two people were discovered in the House of the Cryptoporticus (pictured) and scientists believed that two found in a close embrace were two sisters, a mother and a daughter or lovers. The new investigation confirmed that the victims were male and female and that one was between 14 and 19 years old, while the other was 22 years old.

There were several surprises at ‘the house of the gold bracelet’, the home where the supposed mother and child were found.

The adult wore an elaborate piece of jewelry after which the house was named, adding to the impression that the victim was female.

Nearby were the bodies of another adult and a child believed to be the rest of their family.

DNA evidence showed the four were men and not related, clearly showing that “the narrative long spun around these individuals” was wrong, Mittnik said.

Researchers also found that the ancient humans descended from ancestors who migrated to the region from the eastern Mediterranean, suggesting they had darker features than previously thought.

They were also able to partially reconstruct the appearance of the individuals, finding that one had black hair and dark skin and two others had brown eyes.

This suggested that their ancestors came from populations in the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa, possibly including central and eastern Turkey, Sardinia, Lebanon and Italy.

The researchers said they need to conduct more genetic testing to fully understand Pompeii’s past.

The study’s co-author, David Caramelli of the Universita di Firenze, said: ‘This study illustrates how unreliable stories based on limited evidence can be, often reflecting the worldview of the researchers at the time.’

Pompeii was covered in ash when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD, killing everyone in its path and burying the area.

The city fell into obscurity until its rediscovery in the 18th century, when researchers found dozens of bodies preserved from the soot and ash that covered the streets, buildings and people.

The excavations of Pompeii began in 1748, and although the eruption of Vesuvius completely destroyed the city, the pyroclastic deposits preserved the victims, buildings and art.

The victim’s soft tissue had decayed over the millennia, but their contours remained intact and were restored by filling the cavities with plaster, preserving their DNA.

A Pompeian man, believed to be the keeper of a house, was found all alone in an upstairs room (photo)

When the bodies were first discovered, researchers looked at their position in relation to each other and the location, leading to assumptions about their relationship to each other.

During the excavations at Pompeii in 1914, nine individuals were discovered in the garden of a house, two of which were found close together in an embrace.

Archaeologists at the time said there were three possibilities for their relationship: they were mother and daughter, two sisters or lovers.

After scanning the skeletal remains, investigators have now determined that the victims were male and female and that one was between 14 and 19 years old, while the other was 22.

In another case discovered in 1974, four victims were found in a house and were believed to be a genetically related family.

The first body was that of a four-year-old child who was identified as male because of the bulge in the cast near his genitals.