Dinosaurs may NOT have been wiped out by world-ending meteor: New model says mega volcano eruption may have caused their extinction

A new model has revealed that a megavolcanic eruption pushed the dinosaurs to extinction – and not the infamous one Chicxulub meteor That deposited on the Yucatán Peninsula more than 66 million years ago.

Scientists at Dartmouth University designed a simulation that used real-world geological data to analyze more than 300,000 possible scenarios.

The system was asked to explain the fossil record of a million years before and after the dinosaur extinction.

The model revealed that climate change and toxic gases from the Deccan Traps’ hundreds of thousands of years of emissions were the final nail in the coffin for the extinct creatures.

The Indian megavolcano ‘Deccan Traps’ is estimated to have pumped a whopping 10.4 trillion tons of carbon dioxide and 9.3 trillion tons of sulfur dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere during their nearly million years of eruptions.

The culprit: India’s Deccan Traps megavolcano, which is estimated to have pumped as much as 10.4 trillion tons of carbon dioxide and 9.3 trillion tons of sulfur dioxide into Earth’s atmosphere during its nearly million years of eruptions.

A simulation developed at Dartmouth used 130 processors to test more than 300,000 likely extinction scenarios for the dinosaurs. They found that climate-warming gases from India’s ‘Deccan Traps’ volcanoes were enough to cause extinction 300,000 years before the asteroid hit

The Dartmouth researchers decided to try to leave human emotions between scientists out of the debate, or as they put it, “see what you would get if you let the code decide.”

The researchers fgeological and climate data collected from three deep-sea core samples in their computer model. Each core sample contained fossils from 67 million to 65 million years ago.

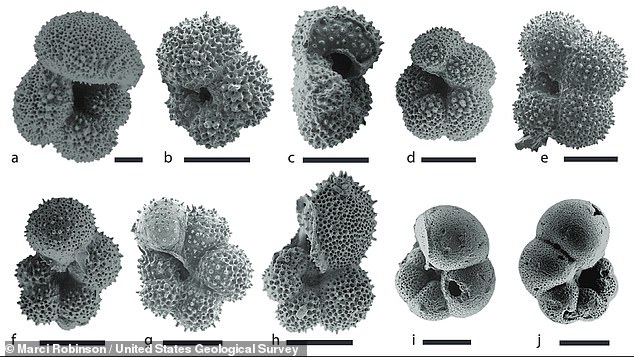

The carbon and oxygen isotopes in the microscopic shells of the many fossilized creatures in the samples, called foraminifera, were used to estimate ancient global temperatures in the years before and after the dinosaurs went extinct.

“We know historically that volcanoes can cause massive extinctions,” explains one of the study authors. ‘But this is the first independent estimate of fugitive emissions based on evidence of their environmental impacts.’

“Our model ran the data independently and without human bias to determine the amount of carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide needed to cause the climate and carbon cycle disruptions we see in the geological record,” said co-author and assistant professor professor of Earth Science. at Dartmouth, Brenhin Keller.

The scientists input geological data collected from deep-sea core samples into their computer model. Each core sample contained microfossils of foraminifera from 67 million to 65 million years ago. Above are ten species of planktic foraminifera, each the size of a grain of sand

“These amounts,” Keller said, “appeared to be consistent with what we expect to see from emissions from the Deccan Traps.”

Keller and his co-author, Dartmouth graduate student Alex Cox, used the ‘Long-term ocean-atmosphere-sediment carbon cycle reservoir‘(LOSCAR) model to calculate the movement of carbon atoms one million years before and after the dinosaurs became extinct.

Their LOSCAR modeling used raw geological data from those deep-sea core samples to simulate the ancient ‘carbon cycle’ – tracking the element’s flows from carbon dioxide gas in the atmosphere to carbon-based life forms such as the tiny foraminifera in the ocean to the foraminifera . fossils embedded in the sediment below.

To help reduce bias and presupposition, Cox and Keller moved their simulation back in time, using a statistical process called “Bayesian Inversion” to determine which scenarios were most likely to have led to their fossil data.

“Most models move in a forward direction,” Cox noted in a press statement.

‘We adapted a carbon cycle model to work the other way, using the effect to determine the cause through statistics.’

This helped eliminate any biases, Cox said, by giving the computer model “only the bare minimum of prior information as it worked toward a particular outcome.”

But performing these tasks backwards took a lot of computing power.

As noted in their new study, published today in the magazine Science128 computer processors running scenarios on a total of 512 cores in parallel were used to simulate the atmosphere before and after the last days of the dinosaurs.

Running these simulations, synchronized in parallel, as Cox said Scientific newsgreatly sped up the process, reducing calculations that could have taken a year to just a few days.

“All processors then compared how they were doing at the end of each model run, like classmates comparing answers,” he said.

The result was a version of the dangerously high levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions during what paleontologists know as the ‘Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event’, which could be attributed entirely to India’s megavolcanoes.

But not all of Cox and Keller’s colleagues are completely convinced.

For example, Sierra Petersen, a geochemist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, told Science News that the ratios of oxygen isotopes in the fossil shells of foraminifera can change due to the composition of seawater, and not just climate.

“It’s a bit of a leap of faith to say that this study shows that the asteroid impact did not cause the extinction,” she says.

“I think what they show is that the impact was probably not associated with major emissions (CO2 and SO2 gas).”

Another researcher, paleoclimatologist Clay Tabor of the University of Connecticut, pointed out that Chicxulub’s impact is estimated to have increased apocalyptic amounts of soot and dust that may have plunged Earth into a grim, fatal winter.

As the debate continues, the Dartmouth researchers insist that they are merely the messenger delivering what their computer model said.

“At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter what we think or what we thought before,” Cox said.

‘The model shows us how we arrived at what we see in the geological record.’