Declassified images from American Cold War spy satellites reveal HUNDREDS of lost Roman forts across Syria and Iraq

American satellites built during the Cold War to monitor the Russians are now revealing fascinating secrets about the Roman Empire.

Researchers have studied satellite images that provide a unique snapshot of the Syrian steppe in the 1960s and 1970s, in what is now Syria and Iraq.

The experts identified the remains of 396 Roman forts – buildings that served as bases for Roman troops during the days of the empire almost 2,000 years ago.

Due to the unique layout of the forts – spread across the region rather than forming a line – the team believes they acted as a base and facilitated ‘the movement of people and goods’.

Other studies have shown that Roman forts once formed a line and therefore collectively acted as a barrier against invaders, becoming places of violent conflict.

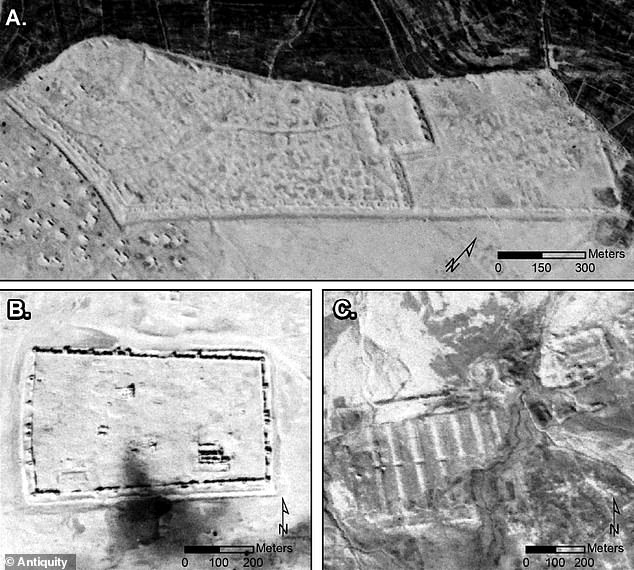

Archaeologists studied declassified spy satellite images from the 1960s and 1970s (pictured) to find forts in part of the Roman Empire

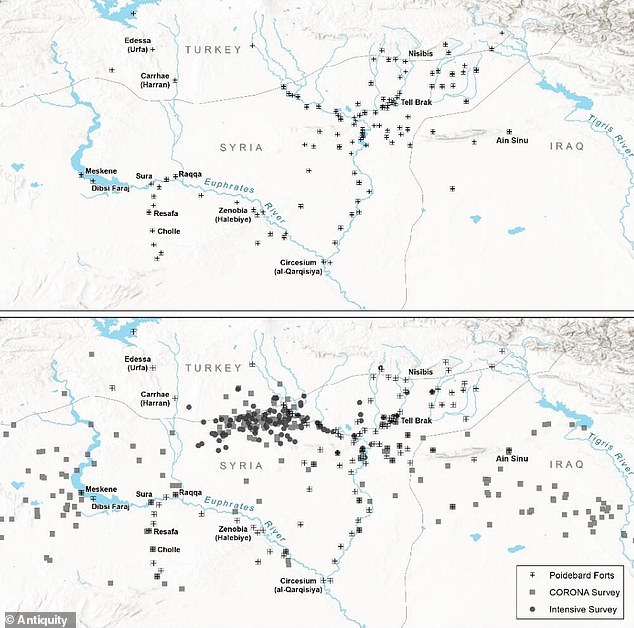

Researchers have studied satellite images that provide a unique snapshot of the Syrian steppe in the 1960s and 1970s, in what is now Syria and Iraq. The team’s study area is highlighted in red

But the new study – conducted by researchers from the Department of Anthropology, Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire – shows that this may not always have been the case.

The team says their results have “dramatic implications” for the modern understanding of Roman life.

“We argue that most – but certainly not all – of the forts documented in this study are likely to be Roman and Late Roman in date,” they say.

‘The structures played a role in facilitating the movement of people and goods across the Syrian steppe.’

It is already known that the Syrian steppe was the site of many fortresses built by the Romans (although, due to the vastness of the empire, fortress remains can be found all over Europe, including Britain).

Even if no traces of the structures can be seen on the ground with the naked eye, their imprint on the landscape can be picked up by aerial imagery, often using light detection methods.

An initial survey of the Syrian steppe was published in 1934 by the pioneering French archaeologist Antoine Poidebard, who took aerial photographs from his biplane.

He recorded a line of 116 forts and noted that their position formed a line and corresponded to the eastern border of the Roman Empire.

As a result, Poidebard was confident that the forts served as a defense line to protect the eastern provinces from Arab and Persian raids from the west.

Pictured: 1934 aerial photographs of selected Roman forts in the region, examined by French archaeologist Antoine Poidebard

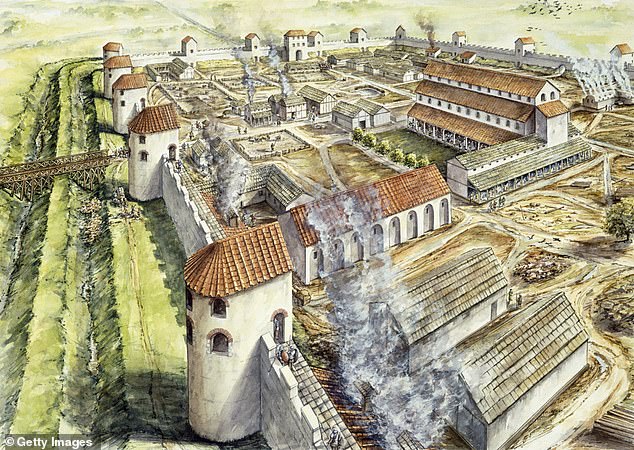

The study’s authors were able to identify 396 Roman forts – buildings that served as bases for Roman troops during the days of the empire almost 2,000 years ago. Pictured here is the Roman fort at Portchester, England in 345 AD

“Since the 1930s, historians and archaeologists have debated the strategic or political purpose of this system of fortifications,” says lead author of the new study, Professor Jesse Casana of Dartmouth College.

‘But few scholars have questioned Poidebard’s basic observation that there was a line of forts that defined the eastern Roman frontier.’

For the study, the team wanted to see if they could find evidence of additional forts that Poidebard had not found, which could potentially challenge the Frenchman’s assumptions.

They used declassified spy satellite images from the Cold War – two different programs codenamed Corona and Hexagon.

“These images were part of the world’s first spy satellite programs, with Corona images collected from 1960 to 1972 and its successor, Hexagon images, collected from 1970 to 1986,” the authors say.

Using the forts found by Poidebard as a reference point, the team was able to identify 396 additional forts, bringing the total to 512.

But what was interesting was that they were found widely distributed across the region from east to west, which does not suggest that together they formed a boundary, as Poidebard had believed.

Instead, researchers believe the forts were built to support trade between the region and protect Roman caravans traveling between the eastern provinces and non-Roman areas.

Meanwhile, the distribution of Poidebard’s fortresses is merely a product of “discovery bias,” the team claims.

“The addition of these forts calls into question Poidebard’s defensive frontier thesis and instead suggests that the structures played a role in facilitating the movement of people and goods across the Syrian steppe,” they write.

They used declassified spy satellite images from the Cold War – two different programs codenamed Corona and Hexagon. Pictured is the Hexagon satellite vehicle

Distribution maps of forts documented by (top) French archaeologist Antoine Poidebard almost a century ago, compared to the (bottom) distribution of forts newly found on satellite images

Images from the American spy satellite program Corona reveal some Roman forts

‘Such forts supported a system of interregional trade, communications and military transport based on caravans.’

Recent research has already reimagined Roman borders as places of ‘cultural exchange’ rather than as barriers where bloody conflict continued to take place.

Although conflict likely took place at the forts, this was probably not their only purpose, the experts suggest.

And although the Romans were a military society, they valued trade and communication with regions not under their direct control.

“We can similarly see that the fortresses of the Syrian steppe allow safe passage across the landscape, provide water for camels and livestock, and provide a place for weary travelers to eat, drink and sleep,” the team adds to.

This indicates that the boundaries of Roman territory were less tightly defined and may not have been the centers of bloodshed and conflict as previously thought.

Because the released satellite images are about half a century old, many of the forts have since been destroyed by urban or agricultural development, the team says.

Hopefully, new discoveries can be made and archaeological sites saved as more declassified images become available, such as photos of U2 spy planes.

The research has been published in the journal Antiquity.