Chancellor MUST act to rescue leisure industry from brink of oblivion, urges boss of UKHospitality

Call: Kate Nicholls wants Jeremy Hunt to freeze business rates in Autumn Statement

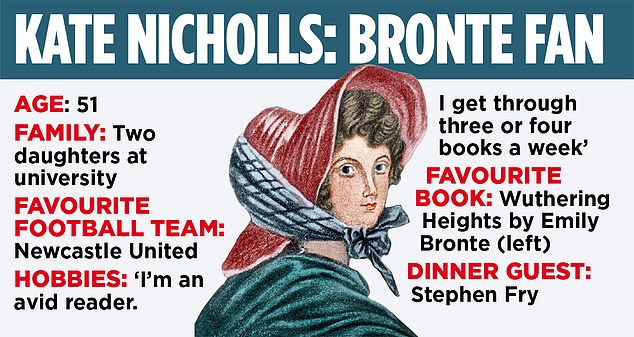

With his autumn statement just days away, Kate Nicholls has a message for Chancellor Jeremy Hunt. As the voice of the hospitality industry, which employs 3.5 million people and pays £54 billion a year in tax, she is demanding urgent action on business rates.

Otherwise, she says, a wave of small businesses will be forced to close next spring because they can’t pay their sky-high bills.

As CEO of UKHospitality, which represents 700 companies in the sector, Nicholls is acutely aware of the toll the past few years have taken.

The pandemic was followed by rising energy bills, runaway inflation, a continued work-from-home trend and rail strikes, which hit travel and socializing.

She fears that if Hunt doesn’t act now, pubs, hotels and restaurants – which are still recovering from the effects of the pandemic – will face another ‘cliff edge’.

Small businesses in the sector currently pay only 25 percent of the hated levy. But in April, all business rates relief for the hospitality sector will end and in addition, bills across the sector will rise by September’s inflation rate – 6.7 percent.

“If the Chancellor does nothing it will mean an extra £1 billion bill for the industry,” she says. “Companies will do business until Christmas and hand back the keys in January.”

Nicholls, 51, admits the Chancellor is in trouble. “It’s probably one of those moments when you lobby more in hope than expectation. Like everyone who puts pressure on the government, we are acutely aware of the tight public finances we face.

“The logic of your arguments – as persuasive as they are – runs up against that hard-headed Treasury Department about how much money is available.” She has even less hope for a VAT reduction. During Covid-19, this was reduced from 20 percent to just 5 percent for the sector – a move that has “saved many thousands of businesses,” she says.

‘It remains the most effective measure we have ever seen. We know that this is the fastest and easiest way to attract investment, get the economy moving and that it is deflationary. It brings prices down.’

But if interest rates were to be cut to 12.5 per cent, it would cost around £6 billion, and that would be expensive.

Nicholls insists the measure will pay for itself over time and draws a comparison to the tourist tax, which The Mail on Sunday is calling on the chancellor to scrap.

“If you cut those taxes, we know it drives growth and recovery,” Nicholls said. “People will come out and eat and drink, so it pays for itself.” And we pay back the Treasury many times over in employment taxes, levies and business rates.”

In her view, the problem is the short-term thinking of the Ministry of Finance. “They only look at the lost costs and revenues,” she says. “They don’t have the ability to build in an assessment of what you could gain if you cut taxes.”

As befits the boss of the British hospitality organization, Nicholls likes to promote destinations. She is from County Durham and is doing very well in sales of her home region.

“It’s a beautiful part of the world, but no one goes there,” she enthuses. ‘There are completely deserted beaches. It’s a secret.’

Her two strongest role models were her mother, who was a teacher, and her grandmother, “an entrepreneur who ran a corner store.”

Is that where she got her hospitality gene? ‘Probably. The store was like Arkwright’s Open All Hours, in a mining community.”

Her formative years came in the early 1980s, during the miners’ strike. Durham was less of a battleground than other mining communities because most mines were already earmarked for closure.

But she remembers how “everyone who worked in the mines” didn’t want their children to follow them.

There was “a strong sense of community and a strong work ethic,” she recalls. ‘Social mobility was a key concept.’

Nicholls, a high school girl, was the first in her family to go to university, studying English at Cambridge.

From there she went first to London, where she worked as a MP researcher in the House of Commons, and then joined a Member of Parliament in the European Parliament, where she honed her lobbying skills.

She held a number of strategic advisory roles, including at Whitbread, before joining the Association of Licensed Multiple Retailers, where she took the top job in 2015.

When the ALMR merged with the British Hospitality Association three years later to form UKHospitality, she became boss of the enlarged group. Then Covid struck.

“Nothing can prepare you for that,” she admits. “It was a fun job to start, but I didn’t know how long it would take.”

As the face and voice of the affected hospitality industry, Nicholls conducted hundreds of media interviews – in addition to countless meetings with policymakers, members and colleagues. You lose count,” Nicholls recalls, but at the height of the pandemic she was doing up to 15 consecutive interviews a day, starting at 5 a.m. and ending at 11 p.m.

‘It was brutal, like a series of marathons interspersed with sprints.

‘It was an incredibly intense and extremely stressful time. I didn’t realize how cruel it was until I stopped doing it.’

She found dealing with the complexities of arrangements such as furlough ‘intellectually stimulating’ and discovered she was ‘much more resilient than I thought I was’.

Nicholls added: “I obviously thrive on adrenaline.”

Covid has made her “wiser and stronger,” but she also admits that “it was a humbling experience. “It puts everything into perspective, I think.”

She remains a strong advocate of hospitality as a career path.

“It’s the ultimate meritocracy,” she claims. ‘You can start with no experience, no qualifications, and in less than two years you can be a manager.

‘I don’t think there is any other industry that invests so much in young people and gives them the opportunity to move up so quickly.’

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on it, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow a commercial relationship to compromise our editorial independence.