Cancer-stricken Connecticut grandmother who pushed for Vermont to expand 'assisted suicide' to out-of-state residents finally gets lethal medication after years of battle

A cancer-stricken Connecticut grandmother who urged Vermont to expand its medically assisted suicide law to out-of-state residents has died from taking prescription lethal drugs.

Lynda Bluestein, 76, who had terminal cancer, ended her life Thursday in Vermont and her husband described it as “comfortable and peaceful,” just the way she wanted.

Her last words were, “I'm so glad I don't have to do this (suffer) anymore,” her husband, Paul, wrote in an email to the Compassion & Choices group.

The organization filed a lawsuit against Vermont in 2022 on behalf of Bluestein, of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and Diana Barnard, a Middlebury doctor.

The lawsuit alleged that Vermont's residency requirement in the so-called End-of-Life Patient Choice and Control Act violated the Commerce, Equal Protection, and Privileges and Immunities clauses of the U.S. Constitution.

Lynda Bluestein, 76, who urged Vermont to expand medically assisted suicide law to out-of-state residents, dies from taking lethal drugs

The cancer-stricken grandmother from Connecticut who had terminal cancer took her own life Thursday in Vermont

Her husband, Paul, described her death as “comfortable and peaceful,” just as she wanted

Vermont agreed to a settlement last March that allowed Bluestein, who is not a resident of the state, to use the law to die there.

Just two months later, Vermont made changes to expand its medically assisted suicide law to anyone in similar circumstances.

It became the first state in the country to change its law so that terminally ill people from out of state could use it to end their lives.

“Lynda was an advocate all along, and she wanted access to this law and she had it, but she and everyone deserves to have access much closer to home, because of the need to travel and make arrangements around planning to coming to Vermont is not something we want people to have,” said Doctor Barnard.

Barnard said it was a sad day because her life was coming to an end. She added: 'But more than a positive edge is the beauty and peace that came from Lynda having a say in what happened at the very end of her life.'

Her last words were, “I'm so glad I don't have to do this (suffer) anymore,” her husband Paul wrote in an email to the group Compassion & Choices

Bluestein was diagnosed with cancer in March 2021. At the time, she was given six months to three years to live.

There are ten states that allow medically assisted suicide, but before Vermont changed its law, only Oregon allowed non-residents to do so, not enforcing the residency requirement as part of a court settlement.

Oregon dropped this requirement last summer.

Vermont's law, in effect since 2013, allows doctors to prescribe lethal drugs to people with an incurable disease that is expected to kill them within six months.

Supporters say the law has strict safeguards, including a requirement that those who want to use it be able to make their health care decision and communicate it to a doctor.

Patients must make two requests verbally to the doctor within a certain period of time and then submit a written request, signed in the presence of two or more witnesses who are not interested parties.

The witnesses must sign and confirm that the patients appeared to understand the nature of the document and were free from coercion or undue influence at the time.

Others express moral opposition to assisted suicide, saying there are no safeguards to protect vulnerable patients from coercion.

Former Vermont lawmaker Willem Jewett, 58, died Jan. 12 by medical suicide after being diagnosed with a rare condition called mucosal melanoma more than a year ago.

Bluestein, a lifelong activist who advocated for similar legislation in Connecticut and New York, which did not happen, wanted to ensure she did not die like her mother, in a hospital bed after a long illness.

Last year she said she wanted to die surrounded by her husband, children, grandchildren, wonderful neighbors, friends and dog.

“I wanted to have a death that was meaningful, but that didn't last forever… before I died,” she insisted.

“I want to live the way I've always lived, and I want my death to be consistent with the way I always wanted my life to be,” Bluestein said.

'I wanted to have freedom of choice when the cancer had cost me so much that I could no longer bear it. That's my choice.'

She had complained that she had not yet reached the point where her life expectancy was less than six months, but that it was her third battle with cancer and that she had seen her mother die from the disease.

“She said, 'I never wanted you to see me like that.' I don't want my kids to see me like that either,” Bluestein said.

“I would like their last memories of me to be as strong as possible, to be able to communicate with them and not in an adult diaper, curled up in a fetal position, drugged out of my head.”

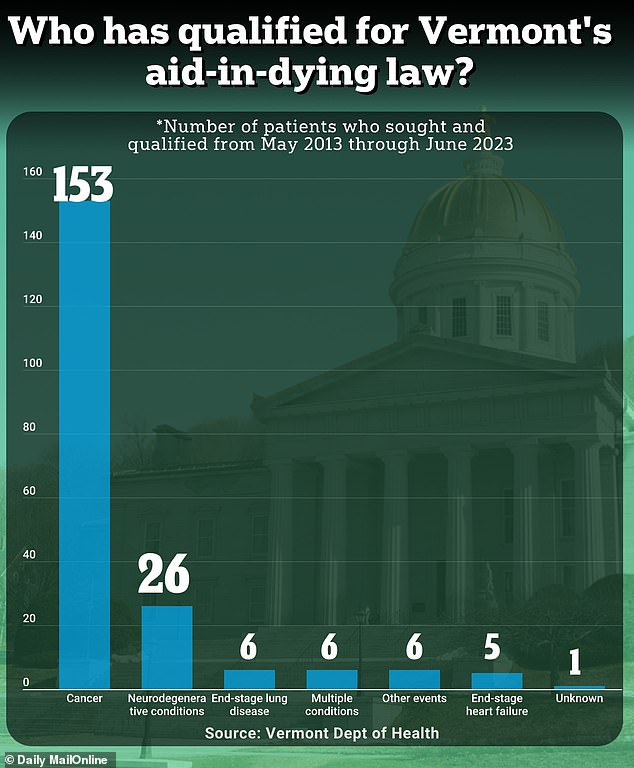

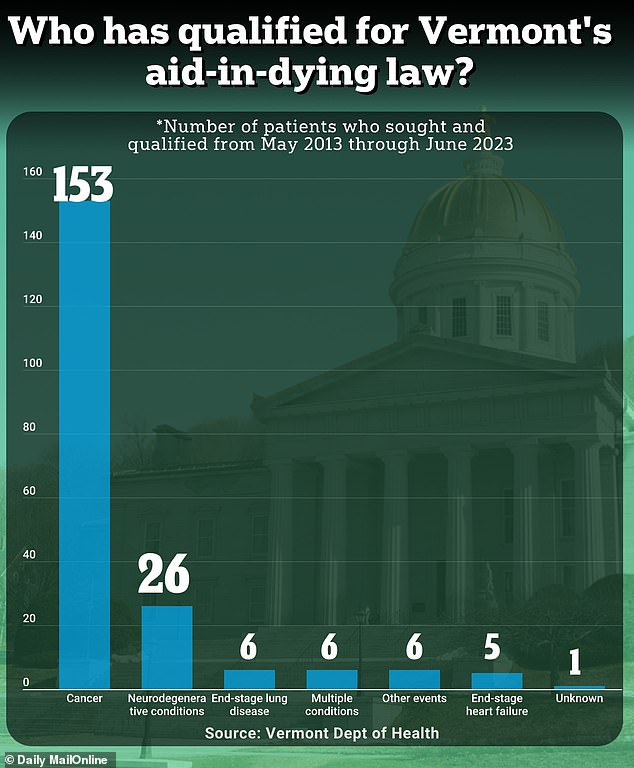

Since the state legalized assisted suicide in 2013, more than 200 terminally ill people in Vermont have chosen to use life-ending drugs over the past decade.

A new report from the Vermont Department of Health shows that 203 patients chose to “die with dignity” between May 2013 and June 2023.

In May 2013, the Vermont General Assembly passed Act 39, which allows capable, terminally ill adult patients to request and obtain a prescription for life-ending medications to hasten their death. Patient and physician participation is completely voluntary.