California start-up’s bold plan to deliver sunlight ‘on demand’ shocks customers

A California startup wants to boost global energy production by selling “sunset” in the evening after sunset using solar panels to create daylight on demand.

Reflect Orbital aims to reflect the sun’s rays across solar panels on the Earth’s surface long after it has become dark. Stunning video footage shows how the technology can light up the night sky with the reflected light.

CEO Ben Nowack presented his company’s ambitious plan at the International Conference on Energy from Space, which took place in London in April.

Many speakers talked about solar panels in space, but Nowack has a different idea. He wants to launch 57 small satellites into orbit, armed with 33 square feet of ultra-reflective mylar mirrors that theoretically bounce sunlight back to solar farms.

The satellites, orbiting 370 miles above the Earth’s surface, could provide solar power plants with an additional 30 minutes of sunlight during peak demand times. The deep dive defeated.

Reflect Orbital co-founders Ben Nowack (left) and Tristan Semmelhack (right) want to revolutionize solar energy and make it a more viable renewable energy source

Pictured: The seven employees of Reflect Orbital. The team recently flew a hot air balloon equipped with a mirror that successfully reflected sunlight onto solar panels

“The problem is that solar energy is not available when we actually want it,” Nowack said at the conference, explaining that solar farms cannot generate energy at night.

His company wants to sell this valuable energy after sunset to solar power plants, which will then send it to people’s homes.

Nowack and co-founder and CTO Tristan Semmelhack also believe that space travel has become cheap enough that operating satellites would not be too expensive. Instead, they believe they can be profitable.

To test the feasibility of their idea, the seven-man team from Reflect Orbital mounted an eight-by-eight-foot mylar mirror to a hot air balloon, intending to reflect sunlight onto solar panels they’d hauled on a truck. A mylar mirror is a glassless mirror made of polyester film stretched over a raised aluminum frame.

They spent weeks in the field improving the process until they finally made a breakthrough.

They shared the shocking results in a YouTube video published in March.

Ultimately, the mirror on the hot air balloon reflected light from a distance of 242 meters (almost 800 feet) onto the solar panels, generating about 500 watts of energy per square meter of panel.

The Reflect Orbital team flew in a hot air balloon equipped with a mylar mirror to test the feasibility of their plan to redirect sunlight to solar farms

The men spent weeks adjusting and calibrating various processes

Eventually they were able to reflect a powerful beam of sunlight directly onto the solar panels on the ground

Pictured: The view from the ground as the balloon bounces sunlight back to Earth

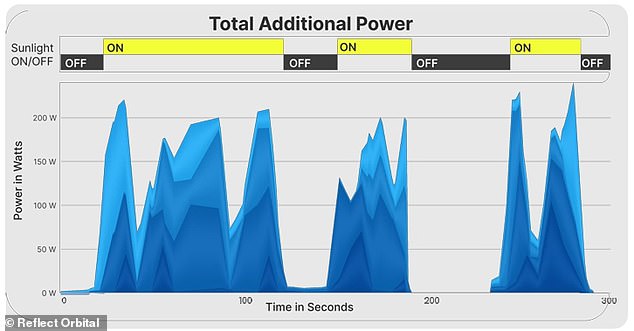

This graph, provided by Reflect Orbital, shows the wattage of power produced during the hot air balloon experiment. The ‘On’ sections indicate when the reflected sunlight is directly focused on the solar panels. The ‘Off’ sections indicate when the sun’s beam is not focused on the panels

“Let there be light!” someone shouts when it is clear that the test has been successful.

To ensure there was no anomaly, a team member removed the panels from direct sunlight for a few seconds.

According to the company’s forecasts, electricity production immediately fell.

People who commented on the YouTube video had mixed reactions, ranging from enthusiasm to curiosity.

‘This is amazing, but also terrifying when you think about it! With only 2 mirrors your buddy on the floor could feel the heat!’ wrote one.

Another wrote: ‘OMG this looks like so much fun to build and test.’

Even Solar energy itself has undeniably become cheaper to produce and manageits inconsistent nature remains a major obstacle to its widespread acceptance as a renewable energy source.

Pictured: A satellite in orbit with reflective mirrors, built by the Russian government in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The project was initially effective, but scientists trying to replicate it after the fall of the Soviet Union ran into major problems. Ultimately, they were unable to replicate the success

Pictured: A rendering of what space mirror satellites might look like

Low, thick clouds and stormy weather can also block sunlight during the day, while there are normally ample opportunities to generate solar energy.

And that’s not even mentioning the seasonal changes that radically alter the amount of sunlight reaching certain parts of the Earth.

While the equator gets more direct sunlight year-round, the Northern and Southern Hemispheres have significantly fewer hours of daylight during their respective winters due to the Earth’s axial tilt of 23.5 degrees.

Reflect Orbital aims to address many of these problems with its mirrored satellites, which can theoretically direct sunlight to anywhere on the Earth’s surface.

Nowack points out that Russia experimented with similar technology in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The Znamya project, as it was called, initially built a satellite with mylar mirrors that effectively reflected sunlight.

But after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, scientists were never able to match this success, mainly because it was very expensive to send satellites into the sky at the time.

The University of Glasgow SOLSPACE projectwhich also gave a presentation at the space conference in London, is also working on orbital solar reflectors.

Now that Reflect Orbital has determined that mirrors can make solar panels more effective on a small scale, the team reportedly plans to launch a prototype satellite next year.

DailyMail.com contacted Nowack and Semmelhack for comment.