Breaking the mold! Scientists are creating different colors of ‘blue’ cheese – and say their pink, yellow and green versions taste just like the real thing

Whether it’s a crumbly Stilton or a creamy Gorgonzola, every foodie knows that a cheese board is not complete without blue cheese.

But these classic varieties may look very different in the future.

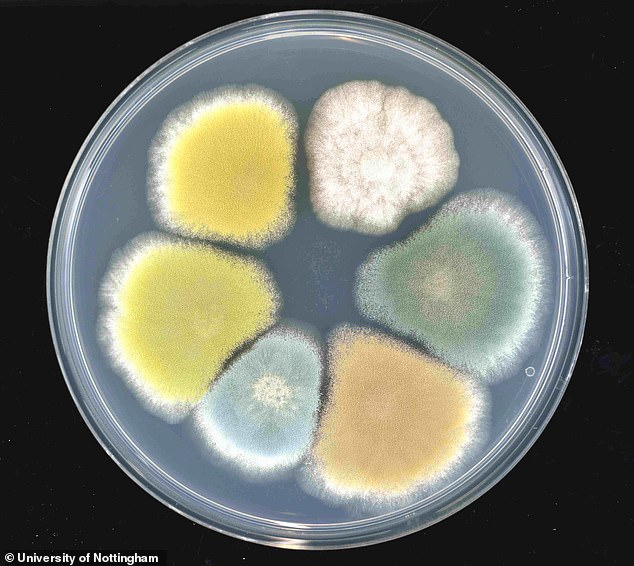

Scientists from the University of Nottingham have devised a way to make different colors of blue cheese.

Despite looking pretty crazy, these technicolor versions taste just like the real deal, according to Dr. Paul Dyer, who led the project.

“I think it will give people a very satisfying sensory experience when eating these new cheeses and will hopefully attract new people to the market,” said Dr Dyer.

Scientists from the University of Nottingham have devised a way to make different colors of blue cheese

Although blue cheeses from different countries around the world can look and taste very different, they are all made with the same mold: Penicillium roqueforti.

As the mold grows, pigmented spores grow throughout the cheeses, giving them both their blue color and flavor.

However, until now, the way this blue pigment is produced is unclear.

In their new study, the team discovered that a biochemical pathway gradually forms the blue pigments, starting from a white color, which gradually becomes yellow-green, red-brown-pink, dark brown, light blue and finally dark blue-green.

Using food-safe techniques, the team was able to ‘block’ this route at certain points, creating species with new colours.

‘We have been interested in cheese molds for more than a decade and when you develop mould-ripened cheeses you traditionally get blue cheeses such as Stilton, Roquefort and Gorgonzola, which use solid mold species that are blue-green in colour,’ says Dr. Dyer said.

‘We wanted to see if we could develop new varieties with new flavors and appearances.

‘The way we did that was to induce sexual reproduction in the fungus, so for the first time we were able to generate a wide range of strains with new flavors, including attractive new mild and intense flavors.

In their new research, the team discovered that a biochemical pathway gradually forms the blue pigments, starting from a white color, which gradually becomes yellow-green, reddish-brown-pink, dark brown, light blue and finally dark blue-green.

After the team produced the cheese with the new color types, they used laboratory diagnostic tools to see what the taste might be like

“We then created new color versions of some of these new species.”

Although the new color versions looked impressive, one important question remained: how did they taste?

After the team produced the cheese with the new color types, they used laboratory diagnostic tools to see what the taste might be like.

‘We found that the taste was very similar to the original blue varieties from which they were derived,’ reassured Dr Dyer.

“There were subtle differences, but not very many.”

Volunteers from across the university tasted the cheeses and revealed some interesting effects of the different colours.

Volunteers from across the university tasted the cheese and revealed some interesting effects of the different colours

‘We found that when people tried the lighter colored varieties, they thought they tasted milder,’ said Dr Dyer.

‘While they thought the dark kind had a more intense taste.

‘Similarly, people thought the more reddish-brown and light green variants had a fruity, spicy element – when according to the laboratory instruments they were very similar in taste.

‘This shows that people perceive taste not only based on what they taste, but also based on what they see.’

The team will now work with cheesemakers in Scotland and Nottinghamshire to create the new color varieties of blue cheese.