Bombshell report exposes UnitedHealth’s callous cuts to children’s health care after CEO’s murder

Health insurer UnitedHealth Group is on a secret mission to reduce operating costs at the expense of thousands of children with autism, research shows.

Previously undisclosed internal documents obtained by ProPublica establish a plan to limit coverage for the gold standard in therapy for children on the autism spectrum, many of whom are poor.

Costs to the company have skyrocketed in recent years, along with autism spectrum disorder diagnoses, thanks to increased awareness and improved screening.

The cost-saving initiative targets children enrolled through the company’s state-contracted Medicaid plans, which serve the nation’s poorest people, including 10,000 children with autism.

The specific therapy that internal documents focus on is applied behavior analysis, which the company itself admits is the “evidence-based gold standard treatment for people with medically necessary needs.”

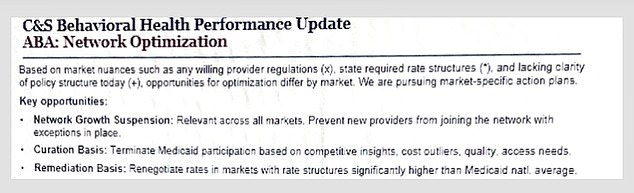

Internal documents show that Optum, which manages mental health services for United, aims to “prevent new providers from joining the network” and “terminate” existing ones, even as it acknowledges there is a national shortage of covered counselors .

The company also conducts “rigorous” clinical assessments to determine the medical necessity of each patient’s therapy, which may lead to a denial of coverage.

UnitedHealth’s leadership is in trouble over a history of denying medically necessary treatment, an issue that allegedly prompted Luigi Mangione, 26, to kill one of the company’s top executives.

Applied behavior analysis is a highly effective form of therapy for children on the autism spectrum that relies on positive reinforcement and repetition. But UnitedHealth’s mental health arm, Optum, is increasingly denying coverage for this ‘gold standard’ therapy in the US

UnitedHealth’s mental health division, Optum, aims to limit network expansion and “terminate” existing providers, including those with higher costs, despite long wait times for qualified providers due to limited coverage

Sharelle Menard’s son Benji was non-verbal for years after being diagnosed with severe autism at the age of three.

As a baby, he was inconsolable and constantly frustrated because he could not communicate with his mother or anyone else.

But after two years of applied behavior analysis treatment in their home state of Louisiana, mumbled words became small words.

He has made great progress with ABA therapy and needs approximately 33 hours per week to make progress.

The downsides of insufficient therapy are significant: from outbursts at school and overturned furniture to classroom assistants scratching and not being able to learn.

Now Ms. Menard is concerned that Benji will deteriorate after receiving notice from Optum that the company is refusing to cover the full number of hours her son needs because he had been in therapy for an extended period of time but was not making enough progress to graduate study. it eventually.

The note from Optum read: ‘Your child continues to struggle with all autism-related needs. Your child still needs help, but it doesn’t seem like your child will improve enough for ABA to end.”

ProPublica’s analysis of internal documents found that the company is pursuing “market-specific action plans” to limit children’s access to ABA.

While it is recognized that some parts of the country have ‘very long waiting lists’ for ABA therapy, some of the ‘key opportunities’ mentioned include ‘preventing new providers from joining the network’, ‘terminating’ existing providers from the program.

Optum calculated that in some states, provider network cuts could impact more than two-fifths of in-network ABA therapy groups and up to 19 percent of patients.

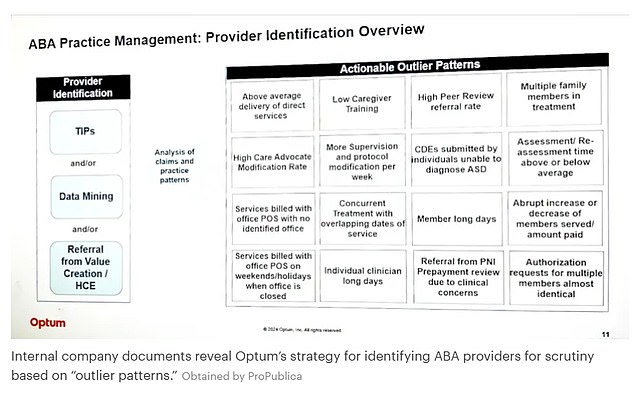

Optum’s internal documents show its strategy for identifying ABA therapy providers that it could rightfully kick out of its network if costs are deemed unusually high compared to other providers in the network

Internal documents show that Optum closely monitored ABA providers based on billings and the number of patients they serve.

Aspire and similar providers may be flagged for common patterns in ABA therapy, including billing on weekends or holidays, treating multiple family members in one session, having long physician or patient days, providing more services than average , or suddenly increasing or decreasing the number of patients. or claims.

Optum has repeatedly disputed claims made by Aspire.

Benji had made tremendous progress by the time he turned seven. His aggressive tantrums had become less frequent, so it was finally possible to leave the house. He could also speak several dozen words.

Mrs. Menard, a pool cleaner, decided it was time to enroll him in a special education program at school.

But when the insurance company decided not to cover the costs, Benji deteriorated with reduced treatment hours.

He would swing during gym class, couldn’t sit still and would bite teachers when they tried to discipline him or give him instructions. Eventually his speech also deteriorated.

Ms Menard said: “This motivation and this momentum – when you lose that, it’s so hard to get it back.

“There’s nothing else I know of that works.”

She had to pull her son out of school and enroll him in a home-study program run by his therapy group, which costs about $10,000 a year on top of his therapy costs, some of which is still covered by insurance.

Benji’s doctors wanted to increase his therapy hours from 24 to 33 per week. They expected the insurer to approve the request as it was less than what was previously covered and only nine hours more than what was currently allowed.

But Optum denied the request in May, telling Ms. Menard and Benji’s therapists, “Your child has been in the ABA for six years.

“After six years, more progress would be expected.”

Joslyn McCoy, the founder of Aspire, is no stranger to Optum denial of care. She has continued to provide necessary therapy hours to children even without being reimbursed by the insurance company

Optum manages mental health services for UnitedHealth Group. It is a major driver of the company’s profits. The latest estimates put revenue this quarter at around $64 billion.

One of Benji’s therapists and the clinical director of the therapy program, Aspire, Whitney Newton, was outraged by the company’s denial. It was not rooted in established medical standards for treatment.

She said: ‘We know what he needs. It falls within our practice and it is our right as a provider to determine that.

“They’re cutting and denying an unethical amount.”

By law, health insurers must reimburse mental health treatments to the same extent as physical illnesses.

A previous ProPublica investigation found that United is in violation of the mental health parity law by applying it selectively a proprietary algorithm that assesses the medical necessity of mental health treatments, specifically ABA.

It was designed to automatically evaluate whether certain therapies were warranted based on predefined criteria.

This led to many denials of coverage for therapies deemed “excessive” or “medically unnecessary,” even when physicians supported these therapies as essential to patient progress.

Although Optum denied coverage for Benji’s necessary treatment hours, his therapists have continued to provide it.

An administrative judge will decide next month on an appeal for the extra hours Benji needs. If approved, Benji’s therapists will be paid for the six months they provide services without being reimbursed by the insurance company.

Even if the appeal is successful, the therapists will have to start over in their dispute with Optum. Each insurance license lasts approximately six months.

So shortly after the hearing, Benji’s therapists will have to reapply for coverage for his treatment.

Joslyn McCoy, the founder of Aspire, said: “We don’t think it would be safe for him to do what the insurance says.”