Beneath the Pacific Ocean is a gigantic volcanic superstructure the size of Idaho

Scientists have unraveled the mystery behind how a volcanic superstructure the size of Idaho formed beneath the Pacific Ocean.

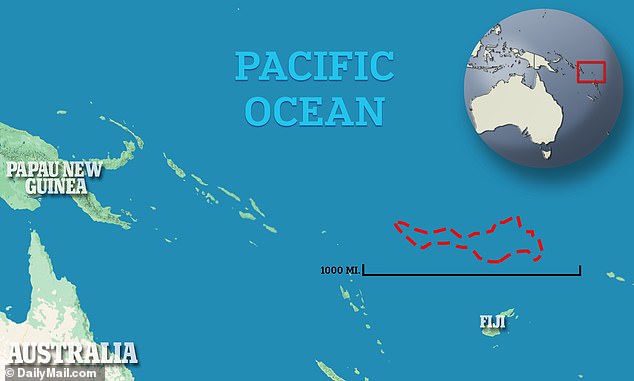

Called the Melanesian Border Plateau, a team of international researchers has determined that the 85,00-square-mile structure was formed when dinosaurs ruled the Earth 145 to 66 million years ago and is still growing today.

Researchers used seismic data, rock samples and computer models to identify four periods of volcanic eruptions deep below the surface that began 100 million years ago.

The submerged structure was also found to be present rare elements used in smartphones, computers and medical devices.

The Melanesian Border Plateau, which is larger than Idaho, is located in the South Pacific, far below the ocean’s surface

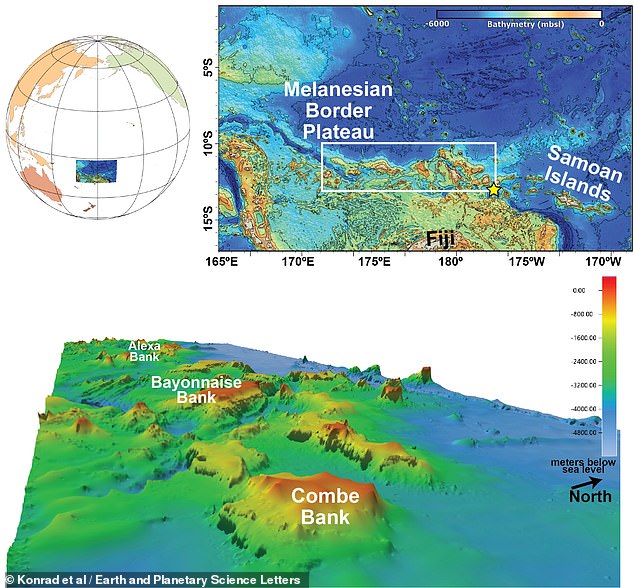

In the new study, an international team of scientists led by Kevin Konrad, assistant professor of geosciences at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, gathered available data to determine the age of the Melanesian Border Plateau.

During a 2013 oceanic expedition, Konrad and his colleagues collected rock samples at multiple points around the Melanesian Border Plateau by dredging deep along the slopes from a ship.

Scientists already know a little about how the Melanesian Border Plateau was formed, but until now they have not been able to paint a comprehensive picture.

By analyzing the age and chemical composition of these rocks, they were able to put the pieces of the puzzle together.

This research is not an easy task, as the water in the area can be up to 600 meters deep.

The work offers a glimpse into the forces that built Earth as we know it, and could provide insight into what the future of our planet will look like.

Researchers used seismic data, rock samples and computer models to identify four periods of volcanic eruptions deep below the surface that began 100 million years ago

Earth’s oceans are full of underwater volcanoes. Their eruptions formed island chains such as Hawaii and Japan, as well as seamounts and ridges that have never pierced the ocean’s surface.

Some structures created by volcanic activity have built up into larger formations over time, usually in one major event at the edges of the plates that make up the Earth’s crust – where two plates meet.

These boundaries between plates are known to be the sites of volcanic activity, so it makes sense that igneous rock (volcanic) formations form here.

But other structures formed over time in the middle of the plates, where there is less obvious volcanic activity. This makes their origin less simple.

The Melanesian Boundary Plateau is one such structure: an oceanic midplate superstructure, as Konrad and his colleagues call it.

At first glance, it may seem as if the Melanesian Border Plateau was formed from a gigantic upwelling of lava from beneath the Earth’s surface.

However, such an event would have registered outside the local area, ejecting large amounts of volcanic material into the water.

“There are some features in the Pacific Basin where (scientists) only have one sample, and it looks like a very large, massive event,” Konrad told me. Living Science. ‘Sometimes, when we study these features in detail, we realize that they are actually built up over multiple pulses over tens of millions of years and would not have significant environmental consequences.’

Rather, it appears that four distinct periods of activity, all with different origins, built up the Melanesian Border Plateau over time.

Researchers used seismic data, rock samples and computer models to identify four periods of volcanic eruptions deep below the surface that began 100 million years ago

According to the new study, the plateau began to form due to undersea volcanic activity during the Cretaceous period, between 145 and 66 million years ago – when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth.

During this first period, a volcanic hotspot called the Louisville Hotspot burned through the lithosphere, the outermost layer of the Earth’s crust, forming a ridge and several small seamounts near what would eventually become the Melanesian Border Plateau.

Hotspots form when lithosphere moves over magma close to the surface.

This was just the beginning of a series of volcanic events.

Between 54.8 and 33.7 million years ago, in the Eocene, some of the earliest mammals spread across the planet.

At the same time, the lithosphere passed through the Rurutu-Arago hotspot, this time forming oceanic islands and underwater mountains.

The third event occurred during the Miocene, between 23 and 5.3 million years ago – when whales and sharks became numerous in the oceans and the first monkeys began to walk upright.

At this time, some of the existing islands and hotspots were reactivated as the region passed Samoa’s hotspot.

“All those same channels that magma passed through 45 million years ago are now pre-existing weaknesses through which magma could pass 13 million years ago,” Konrad said. Living Science.

The period between then and now marks the ongoing fourth pulse of the formation of the Melanesian Border Plateau.

Based on the ages of the past lava flows identified by other researchers, it appears that this most recent phase of the Melanesian Border Plateau was caused by completely different factors than the previous three.

Deformation of the plate boundary in the Tonga Trench has led to new volcanic eruptions, which continues to deposit and build up rock.

The results appeared in the January issue of Earth and planetary science letters.

According to Konrad, the complex formation of the Melanesian Border Plateau may not be so unique.

Other oceanic mid-plate superstructures likely exist, he said, especially in the South Pacific, where volcanic activity continues to shape the region today.

Volcanic activity shaping the region poses no immediate threat to humans.

But understanding it better offers insight into how other undersea structures formed.