Bats ‘surf’ on the wind and travel hundreds of kilometers per night, research shows

When it comes to epic migrations, birds are probably the first animals that come to mind.

But bats also make incredible journeys, with some species able to travel thousands of miles across North America, Europe and Africa.

Scientists have previously struggled to observe these migrations, meaning they have remained a mystery.

To combat this problem, researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior have turned to ultralight intelligent sensors.

This allowed them to study common nocturnal bats during their spring migration through Europe for the first time.

Their analysis shows that these bats use an unusual strategy to travel hundreds of kilometers at night: they surf on the wind.

“They rode storm fronts and took advantage of the support of warm tailwinds,” said Edward Hurme, first author of the study.

‘It was known that birds use wind support during migration, and now we see that bats do the same.’

Noctule bats use an unusual strategy to travel hundreds of kilometers at night: they surf the wind

When it comes to epic migrations, birds are probably the first animals that come to mind. But bats also make incredible journeys, with some species able to travel thousands of miles across North America, Europe and Africa

The ultra-light intelligent sensors weigh just five percent of the bat’s total body mass and can send data back to the scientists via a new long-distance network.

“The tags communicate with us wherever the bats are, because they have coverage across Europe, just like a mobile phone network,” said Timm Wild, senior author of the study.

In total, the team attached tags to 71 bats in Switzerland, focusing exclusively on females, which spend summers in northern Europe and winters in more southern locations.

The tags collected data for up to four weeks as the bats migrated northeast.

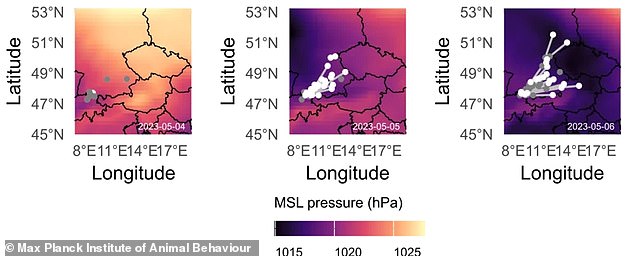

Surprisingly, the researchers found that the bats did not use a specific migration corridor.

“We had assumed that bats followed a uniform path, but we now see that they move across the landscape in a general northeasterly direction,” said Dina Dechmann, senior author of the study.

The tags showed that some bats migrated nearly 250 miles in one night, stopping frequently to feed.

“Unlike migratory birds, bats do not gain weight in preparation for migration,” Ms Dechmann explains.

The ultra-light intelligent sensors weigh just five percent of the bat’s total body mass and can send data back to the scientists via a new long-distance network

‘They have to refuel every night, so their migration is more of a hopping pattern than a straight line.’

On certain nights, the team would see an “explosion” of departures, which they described as “like bat fireworks.”

The explosions can be explained by changes in the weather, with bats moving out at night just ahead of approaching storms.

The sensors showed that bats used less energy flying during these nights, confirming that they were ‘surfing’ the storm fronts.

In this study, the team focused on part of the total noctule bat migration, which is estimated to be about 1,600 kilometers long.

“We are still a long way from observing the full annual cycle of long-distance bat migration,” Mr Hurme said.

“The behavior is still a black box, but at least we have a tool that can shed some light.”

In addition to learning more about bats, the researchers hope the findings will help prevent deadly collisions during bat migrations.

“Before this study, we didn’t know what made bats migrate,” Hurme says.

‘More studies like this will pave the way for a system to predict bat migration.

‘We can be stewards of bats and help wind farms turn off their turbines on nights when bats are passing through.

“This is just a small glimpse of what we will find if we all keep working to open that black box.”