Barbarian warriors in Roman times used ‘stimulants’ in battle, scientists say – after finding small, spoon-shaped objects on their belts

From the British Navy’s use of rum to the German military’s enthusiastic adoption of amphetamines in World War II, the use of narcotics in the military is nothing new.

But now experts have discovered that soldiers have been using drugs to combat anxiety and boredom for at least 1,500 years.

Archaeologists say barbarian warriors may have used ‘stimulants’ to cheer them up before battle, after finding small spoon-shaped objects strapped to their belts.

The researchers claim that these small metal spoons would have been “an excellent way to dose stimulants” while avoiding the risk of a dangerous overdose.

Although a barbarian warrior would not use a modern drug like cocaine, there are a wide variety of herbal stimulants that could have been used.

Fighters may have used powdered drugs derived from opium poppies, hemp, henbane, belladonna and various psychedelic fungi.

Any of these substances in the right dose could provide warriors with the stimulation they need to cope with the stress and strain of ancient warfare.

The use of these drugs may have been so widespread that the researchers suggest there may have been a sophisticated narcotic economy to keep the troops supplied.

Archaeologists say barbarian warriors in Roman times may have used stimulants before battle to reduce anxiety and give them energy (artist’s impression)

Just like in the movie Gladiator, the Germanic tribes of Europe were said to have been fierce warriors who fought against the Roman Empire. But experts now say they may owe some of their ferocity to a dose of narcotic plants

In total, the researchers identified and categorized 241 spoon-shaped objects from 116 locations found mainly in graves in modern-day Scandinavia, Germany and Poland.

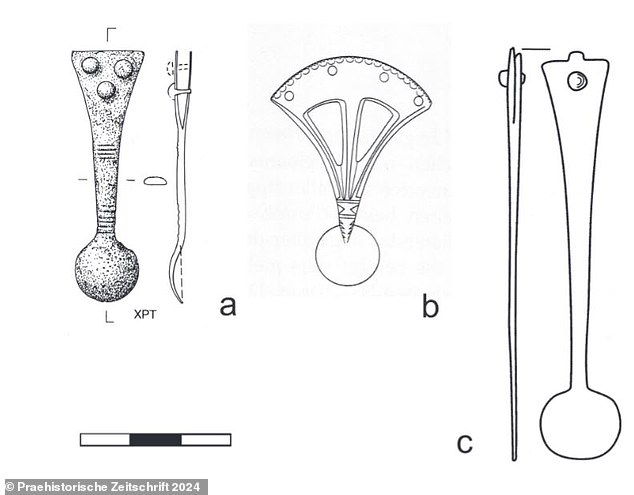

The objects have handles, usually between 1.5 inches and 2.7 inches (40 mm and 70 mm) long, and a hollow cup or flat disc up to 0.7 inches (20 mm) in diameter.

Although surviving examples are largely made of metals such as silver or iron, they may also have been made of wood or antler that has since rotted away.

Although the use of these spoons initially baffled researchers, a clue came from the type of material they were found with.

In their article, published in the Praehistorische Zeitschrift, the researchers write: ‘It turned out that they were all found together with elements of war equipment.’

Combined with the fact that the spoons were strapped long enough to bring them to the face, the researchers suggest they could have been used by warriors to dose narcotics.

The researchers point out that history shows a long record of soldiers using narcotics to stave off the stress of battle and argue that ancient history would not have been an exception to the rule.

Although alcohol was the main intoxicant at the time, ancient societies were well aware of the narcotic uses of plants.

Researchers claim that a series of metal spoons (pictured) strapped to the belts of Germanic warriors were used to dispense powdered narcotics

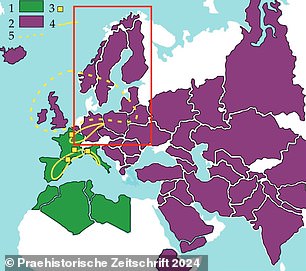

The researchers found 241 of the spoon-shaped objects. Those with round shells were found mainly in modern-day Poland and Germany (left), while those with flat heads were found mainly in Scandinavian graves (left)

For example, the Greeks and Romans grew poppies for opium, who used the opioid for medicine and stimulation.

Similarly, the discovery of a lump of opium in the grave of a fifth-century woman in the Caucasus region of Eastern Europe suggests that drugs may have been used to induce narcotic trances in shamanic rituals.

Because many herbal narcotics can have powerful and often dangerous side effects, it is crucial to get the dosage right.

The researchers therefore suggest that the size of the bowls or discs ‘determined the safest amount of stimulant needed to stimulate the body to increased exertion or to relieve stress.

“Exceeding these doses could have had tragic consequences for the user,” they say.

By analyzing the natural habitat and cultivation area of various plants, the researchers identified a wide selection of narcotics that could have been in powder form or dissolved in alcohol.

For example, an ancient barbarian warrior is said to have sniffed the powdered leaves of the belladonna plant, also known as deadly nightshade.

Although fatal in excessive doses, the tropane alkaloids in the leaves cause increased heart rate, psychomotor agitation, and even realistic visual hallucinations.

Opium poppies (right) are native to Spain, France and parts of North Africa (shown in green) and were widely distributed in Roman times (purple)

The Germanic people would also have been aware of the ergot fungus (photo), which grows on Rye and causes powerful hallucinations. This could have been taken in powder form and taken in small doses as a stimulant

Likewise, the ergot fungus, which grows on rye grains and wild grasses, would have been well known and extremely easy to grow, causing intense hallucinations.

Poisoning by this fungus, also called St. Anthony’s Fire, often led to massive hallucinations and deaths.

Evidence from Spain even suggests that the fungus was used as early as 300 BC to give beer a hallucinogenic kick for use in funeral ceremonies.

Alternatively, a warrior looking for something more relaxing could have used a derivative of hemp, also known as cannabis, which was widely cultivated and consumed throughout Europe.

In their research, published in the journal Praehistorische Zeitschriftthe researchers claim that these ‘agitation stimulants’ were deliberately used for medicinal and even ritual purposes.

“Such use of stimulants by the Germanic peoples of northern Europe was probably widespread during military conflicts in Roman times,” they say.

‘The use of agitation stimulants may have been much greater than was thought.

‘The amount of utensils distributed to promote body efficiency may even testify to its prevalence.’

Warriors may also have taken the powdered leaves or roots of a nightshade, such as Belladonna (right), which is native to most of northern Europe (green) and was introduced to some parts of Scandinavia (purple).

By their estimate, somewhere between a third and a half of all warriors in some locations would have carried spoons for dosing narcotics.

Narcotic use may have been so widespread that researchers believe they have discovered a previously unknown branch of military economics.

They add: ‘Based on our assessment of the level of demand for stimulants in the Germanic armies of the European Barbaricum, this must have been an important industry.

‘There had to be not only a constant demand, but also a need for adequate product quality, which after all influenced the effectiveness of the confrontation with the enemy.’