Baby star’s first ‘scream’ is caught on camera in stunning new photo taken by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope

The arrival of a newborn baby is usually accompanied by dramatic screams – and it seems the birth of a new star in our great cosmos is no different.

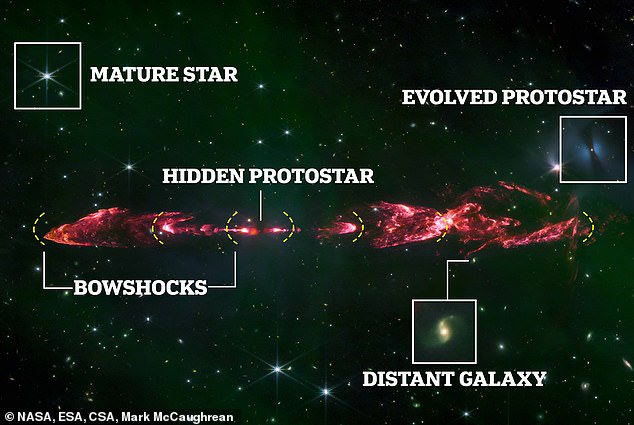

A stunning new photo from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) shows vast red gas jets coming from a newborn star.

This baby star or ‘protostar’ is located at the center of a curious astronomical region called Herbig-Haro (HH) 212, which is visible only as infrared light.

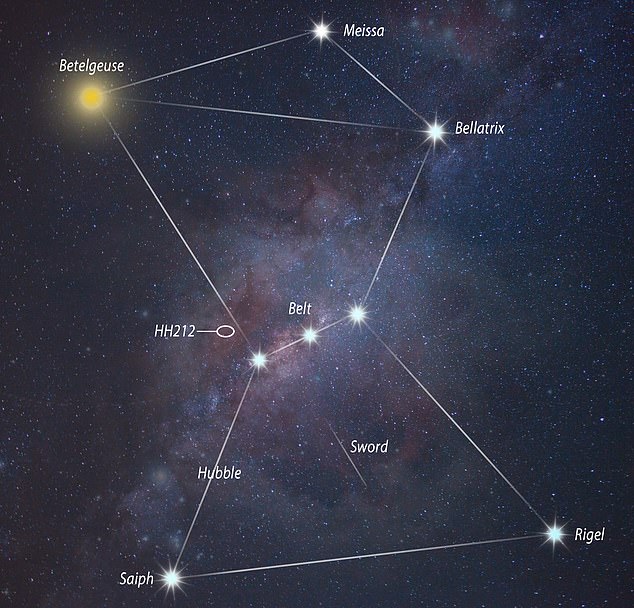

HH212 is located about 1,300 light-years away in the constellation Orion, just like its neighbor HH111, which is known for resembling a lightsaber from Star Wars.

Scientists believe that HH212’s star is no older than 50,000 years – very young in astronomical terms – but will eventually grow to the mass of our Sun.

The stunning photo shows Herbig-Haro (HH) 212, a curious astronomical object located about 1,400 light-years away in the constellation Orion. The young star at the center of HH212 is believed to be no older than 50,000 years, which in astronomical terms is a baby. For comparison, our own star is about 4.5 billion years old and about halfway through its life

By comparison, our own star – the Sun – is about 4.5 billion years old and about halfway through its life.

HH212 has been known for 30 years, but this new image shows the region in unprecedented detail.

“Our new JWST image spans six wavelengths and is ten times sharper than any other infrared image,” said Professor Mark McCaughrean, senior scientific advisor at the European Space Agency (ESA).

‘We first discovered HH212 in 1993 using the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) at Maunkea, Hawaii.

‘We have observed it many times since then with increasingly larger telescopes and with increasingly better infrared cameras and better resolution.

“But it’s safe to say the JWST footage blows all that away.”

In the new James Webb image, which is about 2.3 light-years wide, we can’t see the protostar itself because it is ‘hidden’.

Instead, we see the rose-red ‘jets’ and ‘outflows’ of matter originating in the star and going in opposite directions.

There are also ‘bowshocks’: curved or pointed waves in which faster material collides with slower material in front of it.

In the new James Webb image we can’t see the protostar itself, but the star’s pinkish-red ‘jets’ and ‘outflows’ are prominent

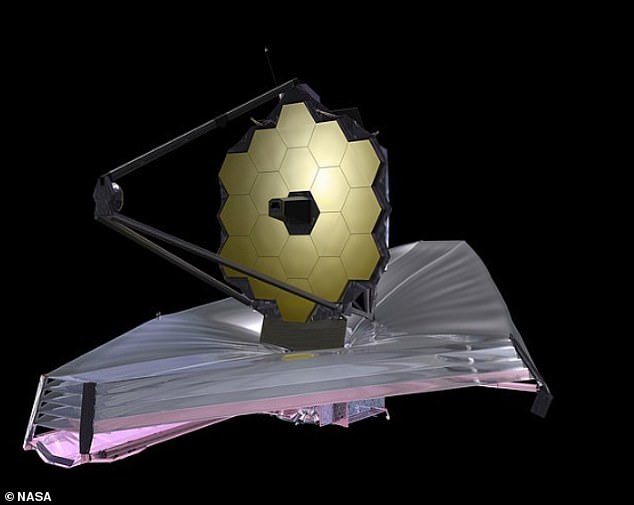

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST, pictured here in space) is the largest and most powerful space telescope ever built

Surrounding the redness of HH212 are older stars that are in the later stages of their lifespan, as well as a distant galaxy.

The blinding color of the jets and outflows indicates the presence of molecular hydrogen, which is energized by the ‘shocks’ in the outflowing material.

The new image was captured by the James Webb Space Telescope’s NIRCam (Near Infrared Camera), which sees the infrared wavelength range.

HH212, located near the ‘belt’ of the Orion galaxy, is almost completely invisible to the human eye because it emits infrared light.

So even if we could somehow visit it, according to Professor McCaughrean, we wouldn’t be able to see it without infrared glasses.

“It’s 1,300 light years away, so even if you travel at the speed of light, by the time you arrive it will have completely changed,” he said.

His comparison with older images of HH212 from JWST’s predecessors, including Hubble, shows that HH212 is moving.

‘As the material moves outwards from the protostar, we can see the jet expanding over time,’ says Professor McCaughrean.

HH212, located near the ‘belt’ of the Orion galaxy, is almost completely invisible to the human eye because it emits infrared light

In areas like HH212, clouds of dust and gas collapse under gravity, spinning faster and faster and growing hotter and hotter until a young star ignites at the center of the cloud.

All the leftover material swirling around the newborn protostar comes together to form an accretion disk, a circular fluid structure made of gas, plasma, dust and particles.

Under the right conditions, the accretion disk will eventually evolve and provide the basic material for the formation of planets, asteroids and comets.

‘Despite all this gas and dust, however, we know that the protostar at the heart of HH212 is quite isolated and not surrounded by large, dense molecular clouds,’ Professor McCaughrean added.

‘How do we know that? Because there are galaxies everywhere in this image, scattered across the image in the distance.

“If there was a dense cloud, we wouldn’t see them.”