Aye up! King Richard III’s accent was more Yorkshire than posh, say scientists

Ever since the acclaimed English actor Laurence Olivier portrayed him on the silver screen, many have believed that King Richard III spoke with a ‘posh’ voice.

But more than 500 years after his untimely death, scientists have revealed what the king must have actually sounded like.

Analysis of the king’s skull, found in 2012, revealed he had a strange accent more resembling Yorkshire than the posh ‘Queen’s English’.

This may come as a surprise to those who saw Olivier’s eloquent performance in his 1955 film based on Shakespeare’s 1592-93 play.

Historians and vocal experts say the approach – to be unveiled at an event in York in November – is the closest we will ever come to “bringing the king back to life”.

King Richard III was memorably portrayed by Laurence Olivier in his film adaptation of the Shakespeare play (pictured)

King Richard III’s voice was reconstructed based on the shape of his skull and information about the speech patterns of the time.

It is not artificially generated, but spoken by a human: London-based actor Thomas Dennis, who appeared as the king at events at Warwick Castle.

The premiere will take place during the ‘A Voice for King Richard III’ event at the York Theatre Royal on Sunday 17 November.

Project leader Yvonne Morley-Chisholm, vocal coach at the Royal Shakespeare Company, spent 10 years researching how Richard III would have sounded.

She coached the actor for ‘countless hours’ to bring his voice as close as possible to that of the king from more than 500 years ago.

‘This has never been done before – this collaboration has been a long time coming,’ she told MailOnline.

‘It was a crazy job to put all the puzzle pieces together.’

Mrs Morley-Chisholm said the King’s skull showed dents and pitting which “give clues to the size and condition” of his muscles at the time of death, as well as his voice.

The project would not have been possible without the discovery of Richard III’s remains in a Leicester car park in 2012 (pictured)

Richard was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field on 22 August 1485 and his body was buried in Grey Friars Abbey in Leicester. However, his bones were removed and lost for centuries. In 2012 they were rediscovered under a car park and the bones were reburied in a new tomb in Leicester Cathedral in 2015. Pictured is a late 16th century oil portrait

Richard III was born at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire and probably spent much of his childhood there. He also spent part of his teenage years at Middleham Castle in Wensleydale, Yorkshire.

Mrs Morley-Chisholm said his accent was “definitely northern” and “looks distinctly Yorkshire”.

Professor David Crystal, a linguist at Bangor University who is also involved in the project, admitted that it is impossible to know exactly how Richard III spoke.

But he told the Times: ‘We will never get any closer than this.’

For the role in his 1955 film, which he also directed, Olivier spoke with a posh accent described as “received pronunciation,” better known as Queen’s English.

The film is based on Shakespeare’s 1592-3 play, which portrays Richard III as an ugly and unpopular hunchback who is “determined to prove himself a villain”.

Stephen Beer, curator at the Medieval Gallery in Dunster, Somerset, said Olivier portrayed the king as “an almost pantomime villain”.

The new voice is not artificially generated, but is spoken by a human – London-based actor Thomas Dennis, who appeared as the king for events at Warwick Castle (pictured)

It doesn’t sound at all like the relatively posh voice of Laurence Olivier in his 1955 film (pictured), which was based on Shakespeare’s play

The event at the York Theatre Royal in November will feature an avatar of the King’s head, created by Face Lab, a group of forensic specialists at Liverpool John Moores University, led by Professor Caroline Wilkinson.

The avatar reads the text of a speech given by Richard III prior to the installation of his son Edward as Prince of Wales in 1483.

“Richard will speak his own words,” Mrs Morley-Chisholm told MailOnline.

“It’s a beautiful piece where he talks about his son – he’s a proud father.”

Partly because of Shakespeare’s play, Richard has long had the reputation of a horrific child murderer.

Although the voice coach admitted she isn’t as knowledgeable as other ‘Ricardians’, she told MailOnline he’s ‘a bit like Marmite – you either love him or hate him’.

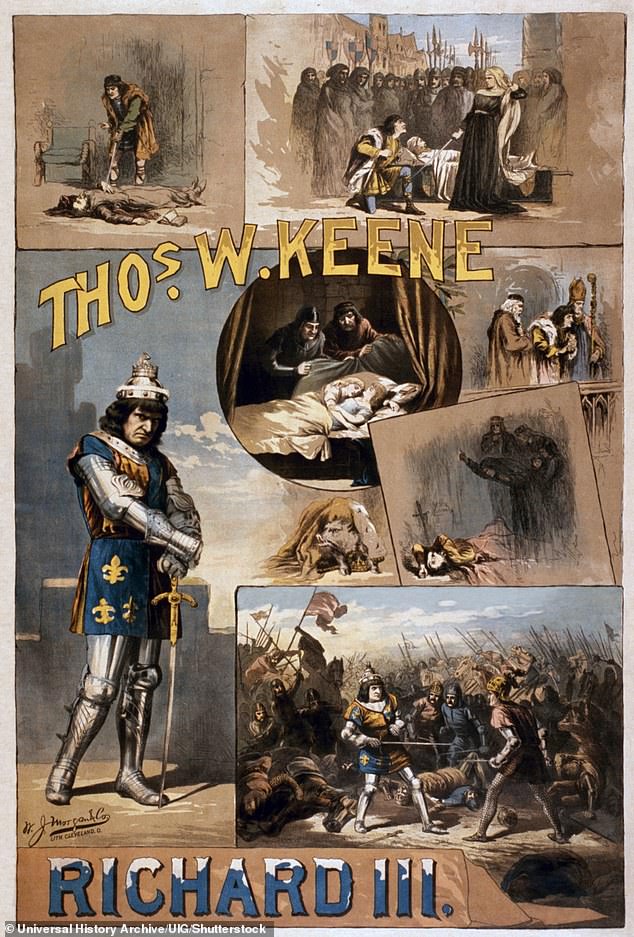

This 1884 poster advertises an American production of Shakespeare’s play King Richard III

Richard III died at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, aged just 32. The event was memorably told in the very first episode of Blackadder.

He led a mounted cavalry charge against Henry Tudor in an attempt to kill him, but Richard was surrounded by Tudor’s supporters who killed him.

His body was taken to the nearby town of Leicester and buried without ceremony, but was not thrown into the River Soar as legend had it.

The new project would of course not have been possible without the discovery of Richard III’s remains in a Leicester car park in 2012 by historian Philippa Langley.

Analysis of the king’s remains revealed that Richard was not actually a hunchback, but rather suffered from scoliosis, a sideways curvature of the spine.

Richard’s body was then carried in a procession through Leicestershire and eventually reburied in Leicester Cathedral in 2015.