Astronaut Thomas Stafford, Apollo 10 commander, dies at 93: Three-star Air Force general commanded a dress rehearsal flight for the 1969 moon landing

Astronaut Thomas Stafford, commander of the Apollo 10 mission, died Monday at the age of 93.

Stafford commanded a dress rehearsal flight for the 1969 moon landing, Apollo 11 and the first U.S.-Soviet space link.

He died at a hospital near his home in Space Coast Florida, said Max Ary, director of the Stafford Air and Space Museum in Weatherford, Okla.

The retired three-star Air Force general participated in four space missions. Before Apollo 10, he flew on two Gemini flights, including the first encounter with two American capsules in orbit.

Stafford was one of 24 NASA astronauts who flew to the moon but did not land on it. The Apollo 10 mission in May 1969 set the stage for the historic Apollo 11 mission two months later.

“Today General Tom Stafford ascended to the eternal heavens he so courageously explored as a Gemini and Apollo astronaut and as a peacemaker in Apollo Soyuz,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a post on X.

Astronaut Thomas Stafford, commander of the Apollo 10 mission, died Monday at the age of 93

The retired three-star Air Force general commanded a dress rehearsal flight for the 1969 moon landing and the first U.S.-Soviet space link. (photo: Stafford in August 1965 with the NASA Motor Vessel Retriever in the Gulf of Mexico during training)

“Godspeed, General Tom Stafford. Thank you for your contributions to NASA and the world,” Nelson added, along with a moving tribute video honoring Stafford.

“Those of us who were privileged to know him are very sad, but grateful that we knew a giant.”

After retiring from space, Stafford became a key figure for NASA as it sought independent advice on everything from human Mars missions to safety issues, to returning to flight after the 2003 space shuttle Columbia accident.

He chaired an oversight group that investigated how to fix the then-defective Hubble Space Telescope, earning a NASA public service award.

Also known as the “Father of Stealth,” Stafford was in charge of the famed desert base Area 51, the site of many UFO theories and home to the testing of Air Force stealth technologies.

During his Apollo 10 journey, Stafford and Gene Cernan, another American astronaut, brought the lunar lander nicknamed Snoopy within ten miles of the moon’s surface.

Astronaut John Young stayed behind in the main spaceship named Charlie Brown.

“The most impressive sight, I think, that has really changed your view of things is when you see the Earth for the first time,” Stafford said in 1997 when talking about the view from lunar orbit.

Apollo 10’s return to Earth set the world record for the fastest speed by a manned vehicle at 25,000 miles per hour.

After the moon landings ended, NASA and the Soviet Union decided on a joint docking mission and Stafford, a one-star general at the time, was chosen to command the American side.

After retiring from space, Stafford became a key figure for NASA as it sought independent advice on everything from human Mars missions to safety issues, to returning to flight after the 2003 space shuttle Columbia disaster.

Stafford in orbit during NASA’s Gemini 9A mission, on June 5, 1966

He took part in intensive language training, was monitored by the KGB while in the Soviet Union, and made lifelong friendships with cosmonauts.

The two teams of space travelers even went to Disney World and rode Space Mountain together before going into orbit and joining ships.

The 1975 mission included two days of the five men working together on experiments. The two teams then toured the world together, meeting President Gerald Ford and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev.

“It helped prove to the rest of the world that two completely opposite political systems could work together,” he recalled at a 30th anniversary meeting in 2005.

The two crews became so close that years later Leonov arranged for Stafford to adopt two Russian boys when Stafford was in his 70s.

“We are too old to adopt, but they were too old to be adopted,” Stafford told The Oklahoman in 2004.

“They have added so much meaning to our lives, and just because you retire doesn’t mean you have nothing left to give.”

Later, Stafford played a central role in the discussions in the 1990s involving Russia in the construction and operation of the International Space Station.

Growing up in Weatherford, Oklahoma, Stafford said he would look up and see giant DC-3 planes flying overhead on early transcontinental routes.

“I’ve wanted to fly since I was five or six years old when I saw those planes,” he told NASA historians.

Stafford attended the US Naval Academy, where he graduated in the top one percent of his class, flew in the backseat of a number of planes and enjoyed it.

He volunteered for the Air Force and had hoped to fight in the Korean War. But by the time he got his wings, the war was over. He attended the Air Force’s experimental test pilot school, graduated first in his class and stayed on as an instructor.

Stafford (right) is survived by his wife. Linda, two sons, two daughters and two stepchildren. (photo: Russian cosmonaut Alexei Leonov (left) and Stafford addressing the media in Moscow in July 2010)

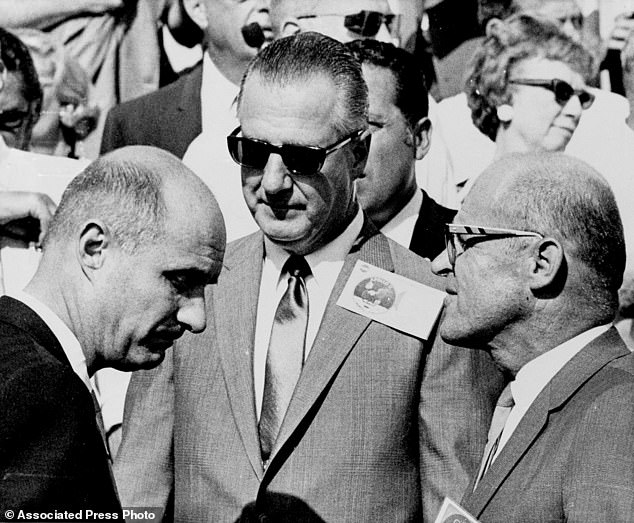

Stafford (left) is seen with Vice President Spiro T. Agnew (center) and Al Siepert, deputy director of the Kennedy Space Center to watch Apollo 11 take off in July 1969

In 1962, NASA selected Stafford for its second wave of astronauts, including Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman and Pete Conrad.

Stafford was assigned to Gemini 6 along with Wally Schirra. Their original mission was to rendezvous with an empty spaceship.

But their 1965 launch was scrapped when the spaceship exploded shortly after launch. NASA improvised, and in December Gemini 6 met but did not dock with two astronauts aboard Gemini 7.

Stafford’s next flight in 1966 was with Cernan on Gemini 9. Cernan’s spacewalk, connected to a jetpack-like device, did not go well.

Cernan complained that the sun and the machine made him extra hot and hurt his back. Then his visor fogged up and he could no longer see.

“Stop it, Gene. Get out of there,” Stafford, the commander, told Cernan.

In total, Stafford spent 507 hours in space, flying four different types of spacecraft and 127 types of aircraft and helicopters.

After the Apollo-Soyuz mission, Stafford returned to the Air Force and worked in research and commanded the Air Force Flight Test Center before retiring in 1979 as a three-star general.

He is survived by his wife. Linda, two sons, two daughters and two stepchildren, the museum said.