As Michael Caine announces his retirement at 90, BRIAN VINER pays tribute to the Billingsgate porter’s son whose acting genius was honed ‘on the bus and Tube’

For some it is Harry Palmer in The Ipcress File, for others Charlie Croker in The Italian Job. Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead in Zulu is a contender, as is Alfie Elkins in Alfie – and even Ebenezer Scrooge in The Muppet Christmas Carol.

But whatever you consider the definitive role of Michael Caine, one thing is now certain: there won’t be any more to choose from.

After a film career spanning 73 years, the venerable British film star has finally called it a wrap, telling Today on BBC Radio 4 that in his old age he will get no better parts than the one he, at the age of 90, is not. currently receiving rhapsodic reviews.

Caine plays the title character in The Great Escaper, the true story of World War II veteran Bernard Jordan, who broke out of the care home where he lived with his wife (played by Glenda Jackson) in 2014 and without telling the staff , made his way across the Channel so he could attend the 70th anniversary D-Day commemorations.

It’s a hugely moving film and Caine is great in it, giving a final counter blast to those who like to scoff that he only ever ‘plays’ himself. On the contrary, he is the epitome of screen versatility.

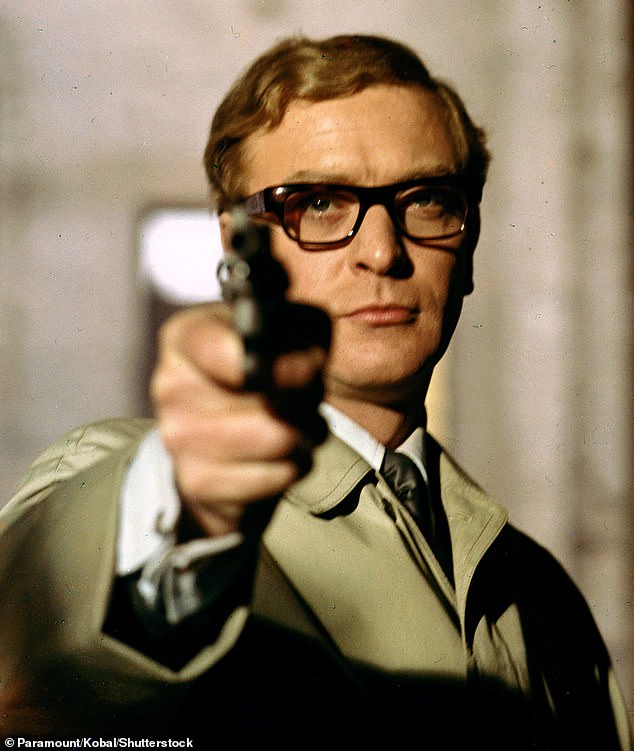

Whatever you consider the definitive role of Michael Caine (pictured in Get Carter), one thing is now certain: there will be no more to choose from

Caine plays the title character in The Great Escaper (pictured), the true story of World War II veteran Bernard Jordan, who suffocated from the care home where he lived with his wife (played by Glenda Jackson) in 2014.

Yes, he has always looked and sounded like him. And yes, like his great mate, the late Sean Connery, his range of accents only ever stretched from A to B. In The Cider House Rules (1999), in which he played Dr. Wilbur Larch, the director of an orphanage in Maine, his New England vocals meandered to Old England.

Still, Caine won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for that performance, his second Oscar after Hannah And Her Sisters (1986), and it was fully deserved. The Academy voters realized what his detractors never did, that what mattered was not his limited vocal range but his expansive emotional range.

He helpfully elaborated on his skills in his 1990 book Acting In Film: An Actor’s Take On Moviemaking, noting that ‘real people in real life struggle NOT to show their feelings’.

In other words, he explained, a character crying his eyes out on screen is not as compelling as a character desperately trying to hold back tears.

Caine’s understanding of what makes people tick has helped him play geniuses, idiots, drunkards, lotharios, adventurers, sleazebags, heroes, warriors, scoundrels and cowards, each as believable as the last, as authentic as the next.

Perhaps it is significant that he did not go to drama school. Instead, the son of a Billingsgate fish porter and a charlady, now a multi-millionaire knight of the realm, claims to have learned the subtleties of human behavior by carefully watching people ‘on the bus and the Tube’ to keep This, he said, taught him “movement and character.”

Of course, there have been some duds over the years. Defiantly indiscreet at times, he accepted a role in the terribly ill-advised 1987 movie Jaws: The Revenge without even bothering to read the script. “I’ve never seen the film,” he later admitted. ‘It was terrible in every way. However, I have seen the house it built, and it is wonderful.’

For a week’s work in the Bahamas on that bad picture, Caine was reportedly paid $1.5 million. The only downside was that the producers wouldn’t let him slip away to Los Angeles for the Oscars, so he wasn’t there to receive his award for Hannah And Her Sisters, the Woody Allen drama in which he excelled as ‘ an unfaithful man. .

Perhaps this was the shark’s true revenge: forcing Caine to miss out on one of the highlights of an actor’s life, walking up to the stage to receive the coveted Oscar statuette for the first time.

Caine was also Oscar-nominated for four performances without winning: for Alfie (1966), Sleuth (1972), Educating Rita (1983) and The Quiet American (2002). It wouldn’t surprise anyone if he gets another nod for The Great Escaper next year, which would underline his extraordinary longevity.

The role that changed his life was that of the aristocratic officer Gonville Bromhead in Zulu (1964). It was a counter-intuitive piece of casting that was never meant to happen; he first tested on screen as the inept Cockney soldier, Henry Hook. But the role of Hook went to another actor and, almost in sympathy, the film’s director, Cy Endfield, asked Caine if he could play ‘posh’.

He did, great. But Caine, the former Maurice Micklewhite, was from London’s Blitz-ravaged docklands. Zulu gave him his breakthrough role, but it was the next few characters he played, in which he was able to draw more on his working-class roots, that made him a star.

Zulu: He played Gonville Bromhead, an upper class officer in Zulu (Pictured in 1963’s Zulu)

Acting Legend: Michael in The Italian Job back in 1969

In 1964, just after seeing Zulu, producer Harry Saltzman spotted Caine having dinner with his pal Terence Stamp at the Pickwick Club near Leicester Square. He sent a note asking Caine to have coffee with him and his family.

Caine knew Saltzman as the producer of the James Bond films; he thought he might land a role in a 007 movie with his friend Connery.

But Saltzman had another plan. He had just bought the film rights to the Len Deighton novel The Ipcress File and saw something in the effete officer from Zulu that made him think he could be perfect as the antithesis of Bond, the ordinary, bespectacled, decidedly unglamorous spy Harry Palmer .

Caine couldn’t have known it at the time (after all, it was just a job, albeit one with a lucrative seven-year contract attached to it), but by inhabiting the role of Palmer so fully, he quickly caused the cultural upheaval of the 1960s.

This was far from visible in some areas of British life, but in others class barriers were being broken down. Beatlemania was in full swing. So a movie star with an unrefined Cockney accent seemed just right for the times.

In many ways, Caine has always reflected the times. In Lewis Gilbert’s 1966 comedy Alfie, he played a lecherous, wildly promiscuous jack-the-lad whose treatment of women – referring to them as ‘it’ – would horrify modern audiences.

The Dark Knight Trilogy: Sir Michael played Alfred Pennyworth, Bruce Wayne’s surrogate father figure, confidante and chief advisor (Pictured in 2012’s The Dark Knight Rises)

Funeral In Berlin: He reprized the role of Harry Palmer (Pictured in 1966’s Funeral In Berlin)

But Caine’s performance as what was then known as a male chauvinist pig was absolutely spot on. Somehow, despite the character’s misogyny, he made him compelling. And it helped us care about him, which in turn reinforced the whole message of the film, that Alfie’s existence is tragic and empty.

Caine gave another of his best performances in another Lewis Gilbert picture, Educating Rita, the 1983 adaptation by Willy Russell of his own stage play. He was simply superb as decrepit, alcoholic college teacher Frank Bryant, and the perfect foil for an equally excellent Julie Walters in the title role.

To think that was 40 years ago and that Caine was already one of the screen’s most enduring stars shows how remarkable it is that he has soldiered on until now.

In fact, he first talked seriously about retirement about two decades ago, when he turned 70. But if he had, we’d have his wonderful turn as Alfred the butler in Christopher Nolan’s Batman films, and one of his lesser-known but most charismatic performances as an elderly vigilante, a former Royal Marine living on a rough estate , in Harry Brown (2009).

He certainly earned his retirement, but that doesn’t mean we won’t miss him. It’s the end of an era, and to paraphrase a line wrongly attributed to him for years: quite a few people know that.