Are YOU an early riser? You may have Neanderthal genes, study finds

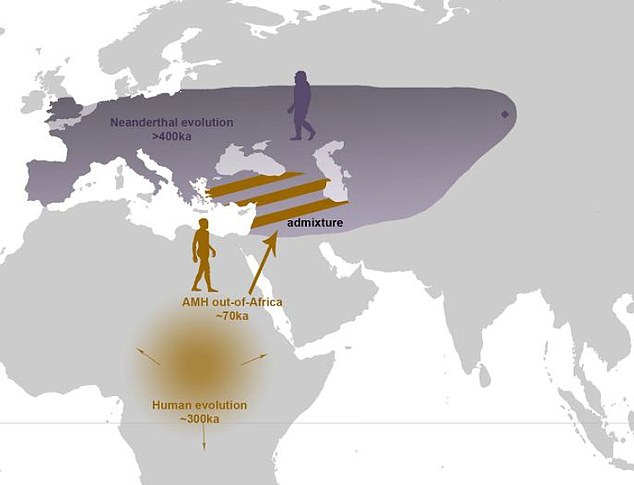

Between 60 and 70 thousand years ago, the ancestors of modern humans were on the move, and their sexual behavior made their modern descendants more likely to be early risers, according to a new study.

By migrating to Europe, our ancestors emerged from Africa and encountered Neanderthals and Denisovans – with whom we share 93% of our DNA.

New research suggests that the three groups interbred and passed on genes that helped subsequent generations adapt to the northern climate and sunlight.

Among these are genetic variants known to be associated with “morningness,” including those shown specifically to regulate circadian rhythms, our wake-sleep cycles.

So, if you tend to wake up early in the morning, this could be the reason.

When ancient humans migrated north into Europe out of Africa, they encountered (and interbred with) the Neanderthals and Denisovans who already lived there. This mixing passed genes to many of their modern descendants, including genes associated with early rise

To find out the impact of ancient genes on modern times, a team of researchers at Vanderbilt University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of California, San Francisco, combed genetic data from a catalog of hundreds of thousands of people in the United Kingdom.

Specifically, they conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) to look for traits associated with early rise.

GWAS look at genetic variants that are statistically associated with a person's traits. In the past, GWAS were responsible for identifying genes that increase people's risk of developing diseases such as kidney disease or insomnia.

They compared these associations with genomes from three ancient hominins that scientists had previously published: a 120,000-year-old Neanderthal, a 72,000-year-old Denisovan found in the mountains of Mongolia, and a 52,000-year-old Neanderthal from the Pliocene. -Croatia Day.

16 different types of genes associated with higher levels of “morning” in modern humans have been woven into the DNA of ancient hominins.

Among these genes are “clock genes” that specifically help regulate our circadian rhythm.

Moving northward, early uplift may have provided some benefits to ancient humans. Shorter circadian rhythms appear to be beneficial for places where days are shorter

It has long been suspected that mixing of DNA between the ancestors of modern humans and hominins passed certain tendencies to their descendants.

Scientists believe that these adaptations may have helped them adapt to moving to northern latitudes.

Compared to Africa, Europe and Asia had greater seasonal differences in weather and sunlight.

The genes identified in the new study may have shifted people toward a shorter circadian period, helping them survive the relatively shorter days.

Research suggests that a shorter biological period helps people adapt to changing conditions more quickly.

“By analyzing the parts of Neanderthal DNA that remain in the genomes of modern humans, we discovered a surprising trend: many of them have effects on the control of circadian genes in modern humans, and these effects are mostly in a consistent direction of increasing the tendency toward morningness,” said lead researcher John Capra. , associate professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco, in a study statement.

“This change is consistent with the effects of living at higher latitudes on animals' circadian clocks and likely allows for faster circadian alignment to changing seasonal light patterns.”

The results appeared today in Genome biology and evolution.

Neanderthals and Denisovans are extinct, but traces of their genetic legacy are still present in many modern humans living today

Modern humans may have benefited from Neanderthal and Denisovan genes, but unfortunately, this genetic Silk Road was not a fair trade.

Neanderthals got the short end of the stick, and previous research has suggested that hybridization with modern humans may have led to a blood disorder that ultimately led to their extinction.

Some important limitations accompany the new research.

First, humans carry many thousands of genes, and behaviors are complex, involving much more than just one or two of them.

Although GWAS can reveal genes associated with early waking, it is difficult to link something as complex as our morning behaviors to just a few genes.

Second, circadian rhythm genes are not just about what time people wake up.

While sleep-wake behaviors are a large part of the circadian rhythm, there are other processes in our bodies, such as digestion, that are dictated by the circadian rhythm.

So genes that influence circadian rhythms may not only influence morning behaviors.

(Tags for translation)dailymail