Are aliens secretly hiding on MERCURY? Planet’s north pole may have the right conditions for ‘extreme forms of life’, breakthrough study reveals

A new study shows that alien life may be even stranger – and closer to home – than we once thought.

Scientists have revealed that Mercury's north pole may have the right conditions to support some 'extreme life forms'.

A new study from the Planetary Research Institute suggests that life could exist in salt glaciers, hidden beneath the surface of the otherwise uninhabitable planet.

The researchers even say that there are similar areas on Earth where life exists, despite the harsh conditions.

“This line of thinking leads us to consider the possibility of subsurface regions on Mercury that could be more hospitable than its rough surface,” said Dr. Alexis Rodriguez, lead author of the study.

Scientists have revealed that Mercury's north pole may have the right conditions to support some 'extreme life forms'

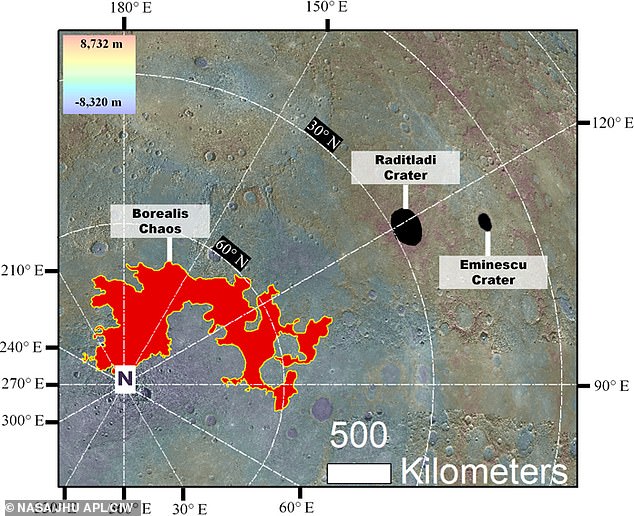

Scientists have found evidence that salt glaciers once flowed into Mercury's Raditladi and Eminescu craters near the North Pole

Using images from NASA's MESSENGER probe, the researchers examined the geology of Mercury's north pole.

Using this data, the researchers discovered evidence that salt glaciers once flowed through the planet's Raditladi and Eminescu craters.

But these glaciers are not like those we know on Earth.

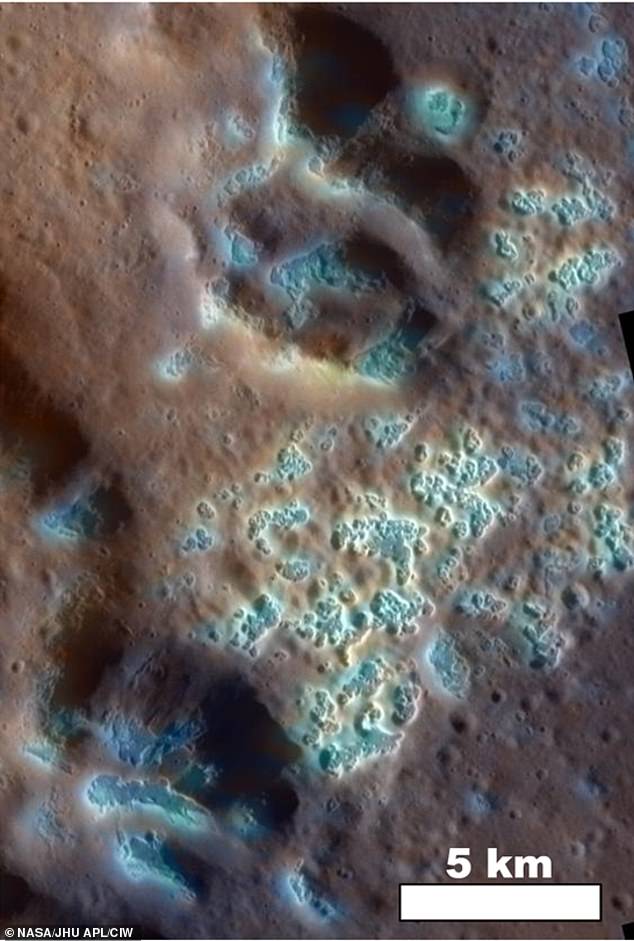

Rather than being made of ice, Mercury's glaciers are made of salts that trap volatile compounds such as water, nitrogen and carbon dioxide.

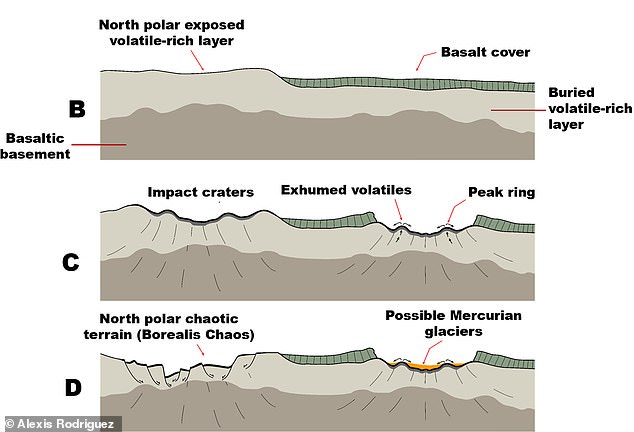

When Mercury was hit by space rocks, craters burst through the outer layer of basalt rock, allowing these volatiles to flow out of the ground and form glaciers.

As the planet closest to the Sun, Mercury reaches daytime temperatures of 430°C, meaning these volatile chemicals have since evaporated.

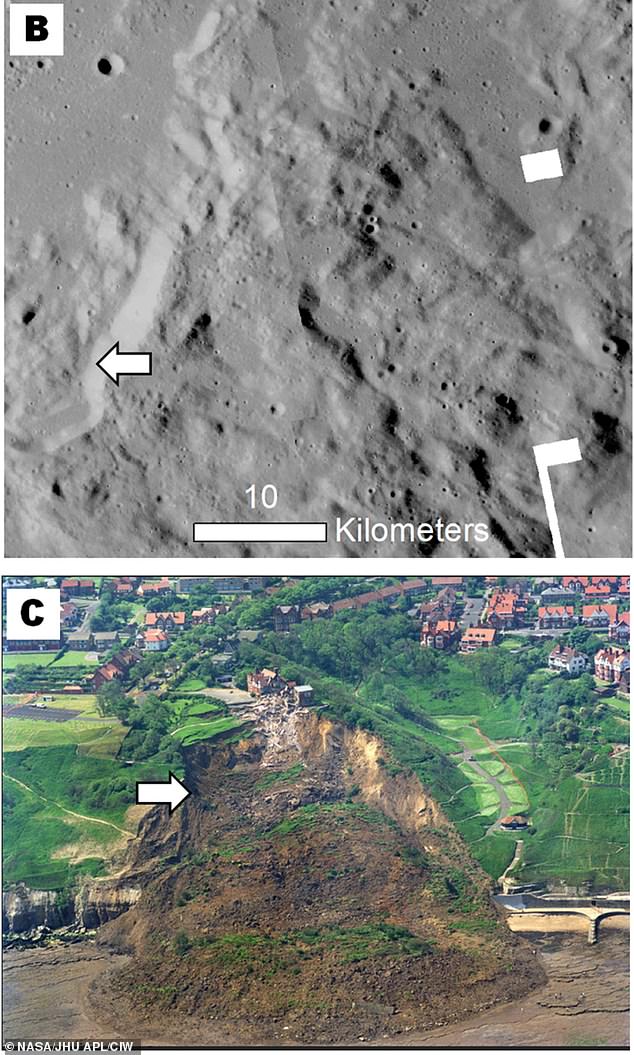

However, the scientists were able to figure out where the glaciers had been by looking for features that were recognizable from Earth.

The researchers used images taken by NASA's MESSENGER probe to look for evidence that there is a layer of volatile-rich salt beneath the planet's surface.

The scientists compared Mercury's craters (top) with geological features found on Earth, such as a landslide at Holbeck Hall, Scarborough (bottom)

Dr. Rodriguez said, “Our models strongly confirm that salt flow likely produced these glaciers and that they retained volatiles for more than 1 billion years after their emplacement.”

This means there is likely a huge layer of salt beneath Mercury's surface, hidden from the sun's fierce heat and packed with volatiles that could support life.

Dr. Rodriguez points out that similar habitats could have supported life here on Earth.

He explained: 'Specific salt compounds on Earth create habitable niches even in the harshest environments where they occur, such as the arid Atacama Desert in Chile.'

Until now, researchers believe that Mercury was completely unable to sustain any life.

This diagram shows how salt glaciers may have formed after a volatile-rich layer beneath the planet's basalt surface was exposed to the sun's intense heat

Researchers say certain salt compounds can support life even in the most extreme conditions, just like here in Peru's Atacama Desert

Scientists believed that the huge temperature fluctuations, lack of atmosphere and constant bombardment of solar radiation made the planet inhospitable.

Although frozen water was found deep in some craters, only in these layers hidden beneath the planet's surface would life have had any chance to develop.

Just as Earth is in a 'Goldilocks zone' at the right distance from the sun, scientists speculate that a similar Goldilocks zone could exist beneath the planet's surface.

Dr. Rodriguez added: 'This groundbreaking discovery of Mercury glaciers advances our understanding of the environmental parameters that could support life, adding a vital dimension to our exploration of astrobiology that is also relevant to the potential habitability of Mercury-like exoplanets .'

This study also offers an explanation for one of Mercury's greatest mysteries.

Mercury's craters are riddled with strange pits and voids in a formation that, according to co-author Deborah Domingue, “has long baffled planetary scientists.”

This research suggests that the pits were formed when glaciers of salt evaporated from the intense heat of Mercury's days, leaving an empty space.

“The proposed solution assumes that clusters of voids in impact craters may originate from zones of VRL exposure caused by impacts,” says Dr. Domingue.

What remains a mystery, however, is how this volatile-rich layer formed in the first place.

Dr. Rodriguez suggests that the layer may have been deposited when a hot, primordial atmosphere collapsed on the planet's surface.

Another solution, proposed by Dr. Domingue, is that dense, salty steam leaked from the planet's volcanic interior and temporarily settled in pools before evaporating.