Archaeologists make surprising find about Martha Washington’s first husband’s family

Archaeologists in Virginia have discovered a lavish colonial-era garden where slaves grew exotic plants owned by the family of Martha Washington’s first husband.

The Williamsburg garden was owned by John Custis IV, a tobacco planter who served in the Virginia colonial legislature and the father of Martha Washington’s first husband Daniel Parke Custis.

Custis’ garden was designed to display his wealth. Excavations revealed that the garden was about two-thirds the size of a football field.

Experts based their correspondence with British botanist Peter Collinson on Custis’s correspondence, which revealed that his enslaved gardeners tended exotic plants and welcomed guests with plants such as the Crown Imperial, which originated in the Middle East and parts of Asia.

“In the 18th century, those were unusual things, only certain classes of people got to experience that. A wealthy person today – they buy a Lamborghini,” said Eve Otmar, Colonial Williamsburg’s master of historic gardening.

Archaeologists in Virginia discovered a lush colonial-era garden where slaves grew exotic plants

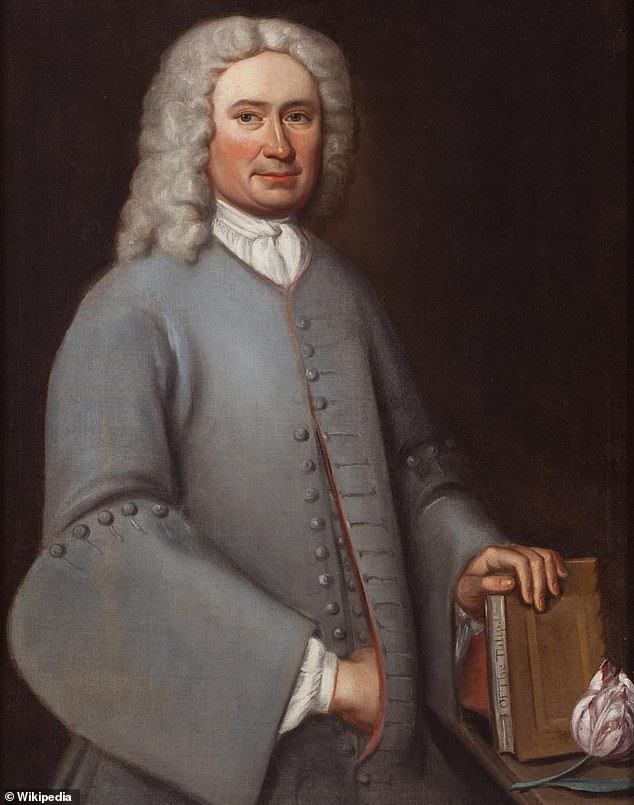

The garden in Williamsburg belonged to John Custis IV (pictured), the father of Martha Washington’s first husband Daniel Parke Custis

A preliminary rendering of the reconstructed garden shows topiaries pruned into spheres and pyramids in the garden

By studying the topography of the area, he saw that his yard had a direct view of Williamsburg’s only church building at the time.

Descriptions from that time mention statues of Greek gods and trees pruned into the shape of spheres and pyramids in the garden.

Crews dug up fence posts three feet thick, cut from red cedar. Gravel paths were exposed, including a large central walkway, and stains in the ground showed where plants grew in rows.

There are also plans to recreate Custis’ Williamsburg home and garden, then known as Custis Square. Unlike some historic gardens, the restoration will be accomplished without the benefit of surviving maps or diagrams, relying instead on detailed landscape archaeological efforts throughout the museum’s history.

Custis is believed to have made one of the first written records of tomato cultivation in Williamsburg. These tomatoes were known at the time as “apples of love” and came from Mexico and Central and South America.

Slaves also planted strawberries, pistachios, and almonds, along with 100 other imported plants. Recent pollen analysis of the soil indicates that stone fruits such as peaches and cherries were present in the past.

“The garden may have been Custis’ vision, but he was not the one who did the work,” said Jack Gary, director of archaeology at Colonial Williamsburg, a living history museum that now owns the property.

Crews dug out fence posts three feet thick cut from red cedar

The excavation also revealed a pierced coin that was commonly worn by young African Americans as a good luck charm

‘Everything we see in the ground that has to do with the garden is the work of enslaved gardeners, many of whom must have been very skilled.’

The dig also yielded a pierced coin that was commonly carried by young African Americans as a good luck charm. Another find is the shards of a clay chamber pot, which was a portable toilet probably used by enslaved people.

Animals appear to have been deliberately buried under some fence posts. These included two chickens whose heads had been removed, and a single cow leg. A snake without a skull was found in a shallow hole that had probably contained a plant.

“We have to ask ourselves, are we seeing traditions that are not European,” Gary said. “Are they West African traditions? We have to do more research. But it’s features like this that keep us trying to understand the enslaved people who were in this room.”