Antarctica is turning GREEN: Vegetation cover has increased more than tenfold over the last 40 years – with climate change to blame

If you are asked to imagine Antarctica, you probably think of a vast white landscape.

But a worrying new study might make you reconsider that image in your head.

Experts from the universities of Exeter and Hertfordshire have warned that Antarctica is turning green, with climate change to blame.

Their analysis shows that vegetation cover on the Antarctic Peninsula has increased more than tenfold over the past forty years.

“Our findings raise serious concerns about the ecological future of the Antarctic Peninsula and the continent as a whole,” said Dr Thomas Roland, who led the study.

If you are asked to imagine Antarctica, you probably think of a vast white landscape. But a worrying new study might make you reconsider that image in your head. Pictured: A WorldView-2 satellite photo of Robert Island (top) and the same post-analysis image, showing areas of vegetated land in bright green (bottom)

Previous studies have shown that the Antarctic Peninsula, like many other polar regions, is warming faster than the global average. In the photo: Green Island

Previous studies have shown that the Antarctic Peninsula, like many other polar regions, is warming faster than the global average.

In their new study, the researchers wanted to understand how much of the area has ‘greened’ in response to this warming.

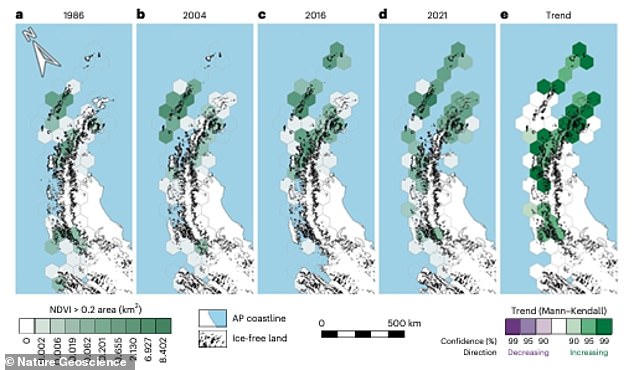

The team analyzed satellite images taken over the past forty years across the peninsula.

The 1986 images show that only one square kilometer of the peninsula was covered with vegetation.

However, by 2021, this area had increased to almost 12 square kilometers.

Speaking to MailOnline, Dr Roland explained that while simple before and after photos would be ‘impactful’, they were not possible.

“Unfortunately, we only have ‘very high resolution’ images from 2013 and 2016,” he said.

‘Although the increase in vegetation we observe in this short time frame is in line with our overall greening trend (1986-2021), the visual difference is not that remarkable!

‘In turn, a single image from the coarser resolution satellite we use for the main study (where we have hundreds of images over the full 35 year period), I suspect, would not be perceived as being of sufficient ‘quality’ to have an impact . .’

The team analyzed satellite images taken over the past forty years across the peninsula and found that vegetation cover has increased significantly

In 1986, only one square kilometer of the peninsula was covered with vegetation. However, by 2021, this area had increased to almost 12 square kilometers. Pictured: Norsel Point

Greening has accelerated in recent years (2016-2021) by more than 30 percent compared to the entire research period (1986-2021) – and grew by more than 400,000 square meters per year during this period. In the photo: the island of Barrientos

The research also shows that greening is taking place increasingly faster.

Greening has accelerated in recent years (2016-2021) by more than 30 percent compared to the entire research period (1986-2021) – and grew by more than 400,000 square meters per year during this period.

‘The plants we find on the Antarctic Peninsula – mainly mosses – grow in perhaps the harshest conditions on earth,’ says Dr Roland.

‘The landscape is still almost entirely dominated by snow, ice and rocks, with only a small part colonized by plants.

“But that small portion has grown dramatically, showing that even this vast and isolated ‘wilderness’ is being affected by anthropogenic climate change.”

Worryingly, the researchers say that as these ecosystems become more established and temperatures continue to rise, the extent of greening will increase.

Experts from the universities of Exeter and Hertfordshire have warned that Antarctica is turning green, with climate change to blame. Pictured: Ardley Island

Dr. Olly Bartlett, co-author of the study, said: ‘Antarctica’s soils are largely poor or non-existent, but this increase in plant life will add organic matter and facilitate soil formation – potentially paving the way for the growth of other plants . .

‘This increases the risk of non-native and invasive species arriving, potentially carried by ecotourists, scientists or other visitors to the continent.’

Based on the findings, the team calls for ‘urgent’ research into the specific mechanisms behind the greening trend.

‘The sensitivity of the Antarctic Peninsula’s vegetation to climate change is now clear and under future anthropogenic warming we could see fundamental changes to the biology and landscape of this iconic and vulnerable region,’ Dr Roland added.

‘To protect Antarctica, we need to understand these changes and determine exactly what is causing them.’