Adopted lab animals rescued from ‘secret’ USDA facility – avoiding deadly cannibalism experiments

>

Violet the hound was kept caged in a dark basement laboratory in Washington DC for most of the first year of her life and never had the chance to play outside.

As a puppy she was deliberately infected with hookworms and plied with experimental drugs as part of a Government-funded pharmaceutical trial, before being fitted with a gastric band by medical students so they could practice before performing the surgery on humans.

Violet was on course to be enrolled in a terminal study where her dead body would have been dismembered for further experiments. But in 2014, she was adopted by Julie Germany, an activist who volunteered to play with lab dogs on her lunch breaks in the capital.

Violet – who now loves going long walks – is one of a growing number of dogs and cats previously confined to cruel laboratories who are getting a second chance at life.

Violet in the basement of the animal testing lab in Washington DC the first day Julie Germany, board member of the WCW Project, met her in spring 2014. Behind her is the trolley of dog toys volunteers could pick from during the daily indoor playtimes Violet was allowed

Violet and Germany playing dress up and enjoying Violet’s post-lab life at Germany’s home in Alexandria, Virginia

In November 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) introduced a policy which forces research facilities to put healthy animals up for adoption or shelter after they have been involved in lab experiments.

It followed a year-long campaign by the White Coat Waste (WCW) project watchdog, which Ms Germany helped co-found the year before she took in Violet.

Until 2019, it was left up to labs to decide what should be done with animals after their initial experiments were completed. Many euthanized them for convenience or to further their research.

Tabby cat Petite and domestic shorthair Delilah were also lucky enough to be adopted before the 2019 policy change.

They had been involved in secret experiments run by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) in Beltsville at a notorious lab dubbed the ‘Kitten Slaughterhouse’.

Delilah was born at the USDA in 2013 and spent her entire life there, while Petite was born in 2015 at a commercial lab breeder and sold to the USDA when she was just over a year old.

Delilah, now nine, and Petite, seven, were two of the 14 breeding mothers at the lab, known as ‘incubator’ cats, used purely to breed kittens for the USDA’s research.

Since 1982, more than 3,000 healthy two-month-old kittens were killed at the Maryland lab after being forced to eat parasite-infected raw meat in a bid to combat toxoplasmosis.

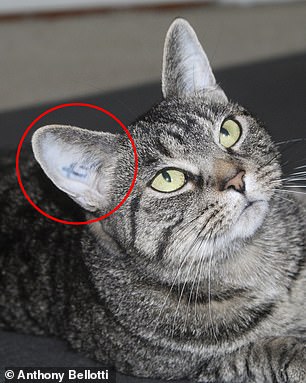

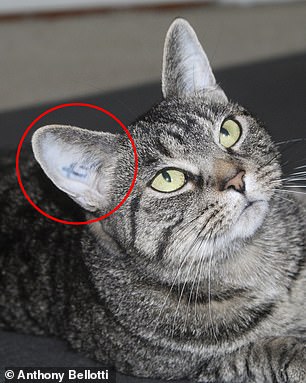

Delilah (pictured left) and Petite (pictured right) with the ear tattoos they were given in the Maryland lab to keep track of them

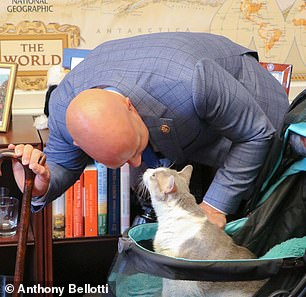

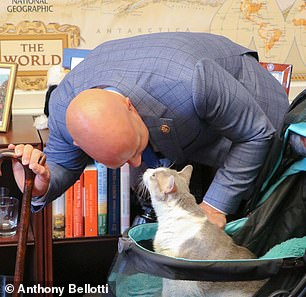

Delilah in July 2019 meeting two members of Congress who helped shut down her lab. She met Senator Jeff Merkley (pictured left) and Congressman Brian Mast (pictured right)

After they were studied for two to three weeks, the lab workers would slaughter the baby cats, put them in bags and incinerate them.

The kittens were also fed cat and dog meat bought from Chinese wet markets in cannibalism experiments.

Delilah had four litters between 2014 and 2016, giving birth to 22 kittens, which were stripped away from their mother at birth, while Petite only had one kitten.

The pair had their government numbers permanently tattooed in their ears.

When they were finally released from the Kitten Slaughterhouse in April 2019, they spent six months in foster care before joining Anthony Belloti, president and co-founder of the WCW Project, and his partner Kellie Heckman, who were instrumental in shutting down the lab.

He said adopting the cats was ‘one of the greatest things of my life that we’ve done’.

‘Not just shutting down that national disgrace, but personally being able to live with the survivors of our work,’ he said.

Belloti and Heckman had to buy the two cats for $1 each to take them back to their St Louis’ home, as the FDA’s adoption policy had not been enacted yet, meaning they had to sell them.

‘That’s the way they think of them, as spent test tubes,’ Bellotti told DailyMail.com.

Due to a lack of proper care inside the lab, Delilah was in need of multiple tooth extractions when she got out and also developed asthma.

She now needs a special cat food diet to control her allergies. She has also suffered from recurring, chronic ear infections, which her vet said is a common ailment for cats who were forced to live in colonies like her lab.

But psychologically, she was very well adjusted to life outside the lab.

Mr Bellotti said: ‘It’s kind of remarkable how loving [she is]. You have a cat like this, a survivor of abuse. She gave birth to 22 confirmed kittens. [The lab workers] picked their up by the scruff of their neck and stuck a needle into their heart, and then put them into a government incinerator. That happened over 22 times to her. The fact that she’s as loving as she is now is remarkable and and we’re very proud.’

A variety of animals — including mice, rats, monkeys, fish and birds — can legally be used for chemical, drug, food and cosmetics testing experiments in America.

But critics have described how the animals’ financial value is valued over their safety and wellbeing, with the animals often confined to tiny cages for long periods of time.

Ms Germany said: ‘The value associated with them is the value of an object or a thing. And once that thing loses its financial value, then it’s worthless. They’re not seen as individuals.’

Violent was kept at the government-funded lab in Washington DC along with two other dogs used for medical students used to practice operations that they would later do on humans.

The dogs were kept in wire cages in a room the size of a long closet, and were allowed out only for daily indoor playtimes with volunteers in the basement.

Germany was working near to the lab in early 2014 and visited on her lunch breaks as a volunteer at the lab to play with the dogs.

She told DailyMail.com: ‘It was just what you’d think of when you think of an American creepy basement. It was dark, it was linoleum, it smelled funny. There was no sunshine — it was a hallway. We’d get out the toys and I played with the dogs.

‘I met Violet pretty early on. She was pretty traumatized when I met her. She was still very young, about a year old. The other dogs in the lab would see me as a person and interact with me and engage with me, it’s like their eyes would rise to be like, “Oh, a human. Feed me, play with me, scratch my ears.”

The day Violet was brought home from the lab in August 2014. Violet was so afraid of grass that she did not want Germany to put her down and kept folding her legs into herself to keep from touching it

‘Violet wasn’t like that. She couldn’t engage with another human being at all. But I watched her play with the dogs around her, and that’s when I fell in love with her. I picked her up to put her back in her cage at the end of the day, and I said to her, “We’re gonna get you out.”‘

One of the experiments Violet was subjected to involved fitting the dogs with gastric bands and feeding them right away so that the band would break.

They were also infected with hookworms – a type of parasitic roundworm that can cause infection and disease in the intestines in humans – and then given different drugs to see how the dogs would react.

The Washington lab allowed volunteers to adopt the dogs once the researchers were done with them.

But if no volunteers were available to adopt them at the time, the dog would be enrolled in a terminal study, which ended with their dead bodies being dismembered.

In mid-2014, Germany’s name got pulled up to adopt the next dog to exit the experiment, but she did not know it was Violet until the paperwork came through.

‘When the vet called, she said, “It’s one of the dogs you were volunteering with.” And I was just like, “Please let it be the worst dog, with the most problems.”‘

She told DailyMail.com: ‘She probably hadn’t seen actual sunlight more than a couple of minutes her entire life. She definitely hadn’t been out on the grass.’

Volunteers would take newly free lab dogs onto grass. ‘You can see them go from being very terrified lab dogs to learning how to be dogs again and do dog things,’ said Germany.

When they got home, Violet was ‘absolutely terrified’ of the lawn.

Germany and her husband were worried Violet had be debarked — where scientists cut the dogs’ vocal cords for convenience — as she did not make a noise for months.

Germany said: ‘When she finally started to bark, it was like she had finally discovered her voice. It took months and months to get her to learn to use the stairs. It took her a year or more to get comfortable going outside to go to the bathroom. She still has some difficulties now, she’ll just get worked up or something, and she’ll go to the bathroom, but we have a really good method for her.’

‘She’s been out for eight years now. She’s a normal dog, like all the other dogs in the neighborhood. She can run around and play and she goes for long walks and cars can drive by and she’s not scared of them. She’s loving and she interacts with people and she helps us foster our cats. She’s become an incredible member of the family.’

The Washington lab was not all bad. Germany said: ‘They had a really nice wall, when you walk into the lab, of pictures of all their former lab dogs and their adopted families. So I guess if you’re going to test on animals, this was a good example of doing what we would like to see happen more often.’

Violet’s Act, named after Violet the dog, is WCW’s current campaign to ensure that government agencies have a plan in place to adopt out or retire all the animals at the end of their experiments.

A study published this month found that former lab dogs are significantly less aggressive toward people and other dogs compared to dogs with no history of lab use.

They are more attached to their caregivers, and just as trainable, it showed.