A simple one-legged balance test determines your biological age – so how old are you really?

Forget expensive MRIs and DNA analyses; testing your age-related health can be done in the comfort of your own home.

Researchers at the Mayo Clinic found that the amount of time a person could balance on one foot indicated important measurements of the health of their bones, muscles and nerves.

The average 50-year-old could balance for about nine seconds, while the average 80-year-old reached almost 3 seconds.

Standing on one foot requires your body to perform a series of complex tasks at the same time.

It requires combining information from small organs in your ear that control balance, visual cues from your eyes, and several large muscle groups in your legs and torso to maintain an upright position.

According to the researchers, this makes it a simple and effective way to measure age-related changes in muscles, bones and nerves.

In 2019, the late Daily Mail contributor Dr. Michael Mosley commented on the benefits of practicing your balance on one leg.

He noted that if you can do this for ten seconds with your eyes closed, you should be in good health, regardless of your age.

The wellness world has turned longevity testing into an industry. Reality TV star Kim Kardashian made headlines last year for promoting full-body MRIs to test for a number of age-related diseases.

Popular biohackers like Bryan Johnson measure everything from their cholesterol to their nighttime erections to get an idea of how they stack up against other people their age.

But scientists, like those on the Mayo Clinic team, are looking for simpler, more cost-effective ways to give patients a sense of their health, both at home and in the doctor’s office.

Science has long known that muscles, bones and movements deteriorate as we age.

It is not clear whether strength, balance or gait start first, and therefore what the best measure of age is.

So researchers at the Mayo Clinic tried to determine this by conducting a series of exercise-related tests on 40 participants between the ages of 50 and 80.

They excluded obese people and those with pre-existing conditions that would affect their balance or gait, and created tests that measured their gait, balance and strength.

“I got eight seconds, not bad for a 62-year-old,” said Dr. Michael Mosley (pictured)

For strength testing, they used a custom-made device to test the participants’ grip strength and a test that involved straightening the knee as quickly as possible.

In the walking test, participants walked back and forth on a 7-meter walking path at a comfortable speed while wearing motion detection sensors three times.

They used measurements such as speed, stride length and stride length.

Finally, in the balance test, individuals were tested on two legs and one leg.

For the two-legged test, they were instructed to look forward, once with their eyes open and once with their eyes closed, and place their feet on two force plates – which measure how much force someone exerts on the ground.

For the one-leg test, physical therapists told participants to stand up straight with their arms in whatever position was comfortable.

They then had to lift and hold one leg at a time for however long they were able to maintain their balance.

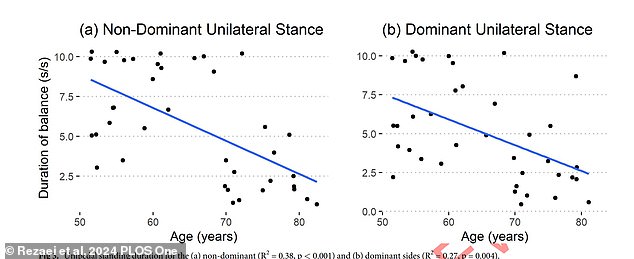

The two graphs show how long a person was able to balance on their dominant and non-dominant feet, one at a time. On the non-dominant foot, the time participants could stand decreased by 2.2 seconds per decade

The way they walked didn’t change significantly as people got older, but the amount of time their balance, grip and knee strength did change. The findings were published in the journal of the Public Library of Science.

The measurement that changed most with age was balancing on one leg. Researchers say this is a good measure of frailty, independence, risk of falls and nerve damage to the limbs.

With each decade a person grew older, the time a person could stand on their non-dominant leg decreased by 2.2 seconds. So if a 50 year old person could balance for 15 seconds, a 60 year old person could balance for 12.8 seconds. .

For the dominant leg, the time they can hold drops by 1.7 seconds per decade.

The researchers said this test could be implemented in doctors’ offices as a low-cost, low-tech way to test bone strength and aging.

They said: ‘This finding is significant because this measurement does not require specialized expertise, sophisticated tools or techniques for measurement and interpretation. It can be easily performed even by individuals themselves.”

Having an idea of where you are in terms of your neuromuscular health can help you create a wellness plan that works for you.

For example, if there is a lack of strength or bone mass, a person can incorporate light weight training into his or her routine to try to regain some strength.

The researchers concluded that these results “may help optimize these exercise and maintenance programs to improve balance and strength in older adults, thereby delaying or avoiding disability.”