We must be cautious, but the power vacuum in Syria has presented the West and Trump with a golden opportunity: PATRICK BISHOP

When I arrived in Damascus 35 years ago, on my first visit as a foreign correspondent, I expected a gray swamp of dictatorial repression.

This was, after all, a country under the iron grip of despot Hafez al-Assad, who just seven years earlier had slaughtered twenty thousand of its inhabitants while crushing an Islamist uprising in the city of Hama.

Instead, I found a capital that – at first glance – seemed colorful and rather relaxed. Restaurants and coffee shops were full and customers were cheerful.

Mosques and Christian churches stood side by side, and the antique shops in the old city were largely owned by Jews – an echo of the country’s long phases of religious coexistence.

It’s true that Assad’s hatchet face looked down from billboards everywhere. But the rule seemed to be that citizens who did not raise their voices against the leader – the so-called ‘Lion of Damascus’ – would be granted a degree of personal freedom.

When his son Bashar succeeded him in 2000, there were hopes that the timid, soft-spoken, London-trained ophthalmologist would usher in a degree of liberalization. And so it seemed for a while, with cautious signals from the regime that reforms were in the air.

But the Damascus Spring was short-lived. In 2011, Bashar’s forces acted with unchecked brutality to crush protesters calling for an end to the Assad clan’s tyranny, killing at least 5,000 demonstrators and dissidents in one year.

It was the start of a civil war in which Bashar proved himself to be just as ruthless and bloodthirsty as his father. Murder, torture, rape, mass incarceration and military raids that showed a bloody disregard for civilian life kept him in power – aided and abetted by his fellow despots in Moscow and Tehran.

Opposition fighters celebrate as they burn down a military court in Damascus

The damage to the country is indescribable. Cities and towns are in ruins; 600,000 Syrians are dead, half of them civilians; more than 13 million people have fled their homes. It is no wonder that the flight of the disgusted Bashar has been welcomed with great joy.

Commentators are quick to pour cold water on the naive assumption that the country’s nightmare is over.

They point to similarly ecstatic scenes after the fall of Saddam Hussein in Iraq in 2003, and Muammar Gaddafi in Libya eight years later. Both countries quickly descended into factional fighting, violence and anarchy.

The former head of MI6, Sir Alex Younger, warned yesterday that what comes next is likely to be ‘a resurgence of civil war and conflict in all its dimensions’.

We must rightly be very careful. Half a century of dictatorship has brutalized large parts of the population and fragmented social cohesion. Black pessimism is rarely unfounded when it comes to events in the Middle East.

But now that the dust has settled, I feel like we may be seeing a glimpse of some signs of hope. Syria is not Iraq. There, regime change was imposed by the US without a nation-building plan in place or an internal opposition capable of implementing it.

The Syrian uprising is homegrown. It may have been supported by outside powers and contain elements that are rightly alarming to the West. However, the fundamental agenda – getting rid of Assad – was simple and difficult to disagree with.

The rebels may be Islamists, but they are also nationalists who say they want Syria to heal and function.

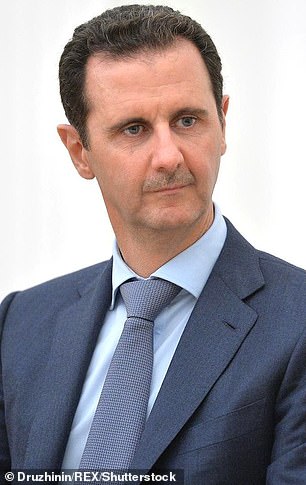

After the fall of Assad (right), Donald Trump would do well to reconsider his thoughts that ‘this is not our fight’, writes PATRICK BISHOP

What happens when the euphoria wears off is the big question – and here too there are reasons to allow ourselves a little optimism.

So far, the main rebel group Hayat Tahrir-al Sham (HTS) has proven to be disciplined, effective and politically agile. So far there has been nothing on the scale of the wild looting seen after the fall of the Iraqi cities of Basra and Baghdad in 2003. However, the group has caused unrest in some quarters – not least given its support which she received from Hamas terrorists in Gaza.

But the leader of HTS, and for now at least the de facto ruler of Syria, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, seems determined not to scare the horses. He has gone to great lengths to soften the image of himself and HTS, swapping his jihadist clothing for a blazer and open-neck shirt for some media meetings.

He is every casting director’s dream of an Arab rebel sheikh: handsome, noble in bearing and with a hint of a twinkle in his brown eyes.

His script for the future, as presented in a CNN interview last week, could have come straight from Nelson Mandela’s mouth. He admitted that he had an inciting past as ’emir’ of the Syrian branch of Al Qaeda, but claimed that time had softened him.

“A person in their 20s will have a different personality than someone in their 30s or 40s,” the 45-year-old said.

The emphasis is on building strong state institutions and reunifying the country with equal rights for every citizen, regardless of sect or clan.

In a bid for Western support, Jolani has cleverly argued that Assad’s demise is a victory for everyone – except Russia and Iran. He insists that a peaceful Syria could stem immigration flows and bring back refugees from Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Europe – including Britain.

It is one of many powerful arguments that should push the West to take swift action to stabilize the situation. Donald Trump in particular would do well to reconsider his thoughts that “this is not our fight” and that “the United States should have nothing to do with it.”

This is unlikely to be the president-elect’s last word on the issue, as during his last term in office his policy on Syria shifted sharply from withdrawal to engagement and back again. The truth is that the US – and the rest of us – have a whole pack of dogs in this fight.

For starters, the Islamic State jihadists, who once plunged parts of the region into medieval barbarism, are currently under control; many of them are locked up in detention camps run by Syrian Kurds with the support of about a thousand American troops.

But if Trump were to order Americans home, ISIS diehards could break loose to regroup and resume their terror campaign.

But there is something even bigger at stake. The power vacuum created by Assad’s flight has presented Trump and the West with a golden opportunity.

A stable Syria is in the interest of every well-intentioned power. With Iran deflated and Russia weak from repeated humiliations in both Syria and Ukraine, this is an opportunity to replace their malign interference with positive support.

With the help of practical help from the US and Europe, houses can be rebuilt and refugees can be repatriated. This could be the start of a positive partnership with Damascus that could heal the deep wounds of the past.

Trump’s “America First” doctrine is jostling for his desire to have his name engraved in history. In time, Syria could become a cornerstone of a broader Middle East peace based on the 2020 Abraham Accords launched during Trump’s first presidency. This began the process of normalizing relations between two Gulf states with Israel, but this was derailed by the October 7 massacre last year.

Although recent history might suggest otherwise, Syria is not doomed to endless intercommunal conflict. The Damascus of intermingled mosques and churches that I saw in 1989 was not a mirage, but an echo of a long, if intermittent, past of harmonious coexistence.

Events have now conspired to offer hope that Syrians may experience it again.

- Patrick Bishop is a former Middle East correspondent and co-host of the Battleground podcast with historian Saul David.