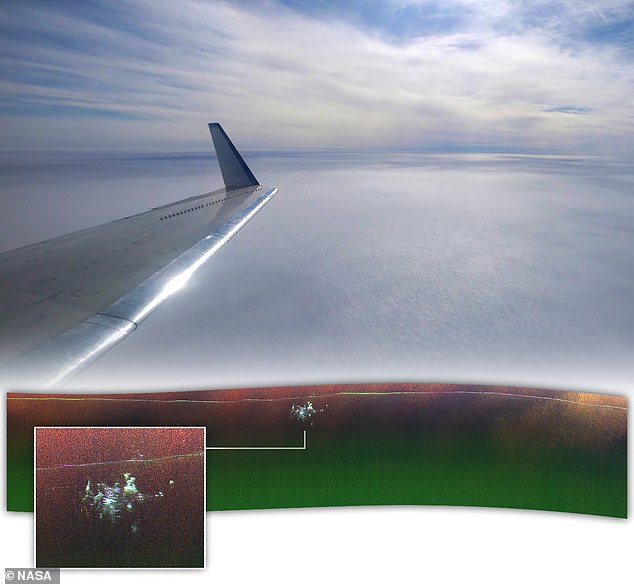

Secret Cold War nuclear base hidden beneath the ice cap is captured in a stunning photo by a pilot flying overhead

A NASA scientist has discovered a defunct Cold War military base hidden deep beneath the Greenland ice sheet.

Chad Greene, a cryospheric scientist at the Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), was flying a plane over the massive glacier when the radar unexpectedly spotted something hidden in the ice.

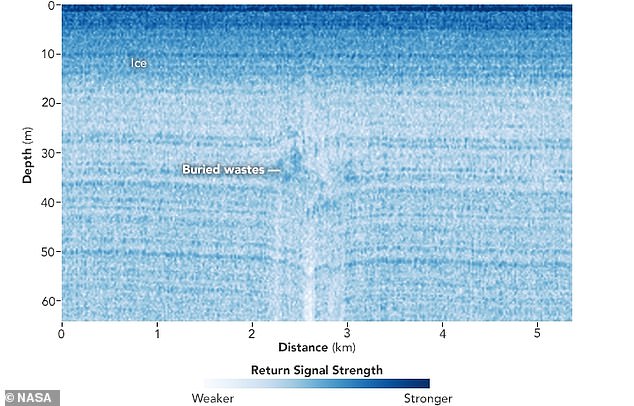

Previous radar images of Camp Century appeared to be nothing more than a “blip,” but the new map revealed 3D structures that matched the design and structure of the base.

The camp was spotted about 150 miles east of Pituffik Space Base in northern Greenland.

“We were looking at the bottom of the ice and out came Camp Century,” says fellow JPL cryospheric scientist Alex Gardner, who co-led the project. “We didn’t know what it was at first.”

Camp Century, also known as ‘the city under the ice’, was an American military base built in 1959. It consists of 21 tunnels bored just below the surface of the ice sheet, with a total length of 3,800 meters.

It was used as a front for Project Iceworm, which aimed to install a vast network of nuclear missile launch sites that could target the Soviet Union.

But due to the instability of the ice sheet, the project – and Camp Century – were eventually abandoned in 1967, gradually becoming buried under snow and ice.

NASA scientists have captured an image of an abandoned US military base hiding beneath the ice

Chad Greene, a cryospheric scientist from NASA JPL, was flying a Gulfstream III over the massive glacier when radar unexpectedly spotted Camp Century

The facility’s infrastructure now lies at least 30 meters below the surface of the ice sheet.

Previous aerial surveys flying over Camp Century have discovered signs of the base in the ice.

But those flights used conventional ground-based radar, which points straight down and produces a 2D profile of the ice sheet, according to a NASA Earth Observatory statement.

The latest discovery used radar to map an ice sheet’s surface, internal layers and underlying rock, similar to the way doctors use ultrasound to see inside the human body.

Greene’s flight, which took place in April 2024, used NASA’s Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar (UAVSAR), mounted on the floor of the aircraft.

This system not only looks down, but also captures a side view to image solid structures with more dimensionality.

“The new data reveals individual structures within the Secret City in a way never seen before,” Greene said in the statement.

The scientists used this data to map the structure of this lost base, and it appeared to match historical records of its planned layout.

Camp Century is a US military base built in 1959 and consists of a network of 21 tunnels, just below the surface of the ice sheet, with a total length of 9,800 feet

Previous airborne surveys flying over Camp Century used conventional ground radar, which points straight down and produces a 2D profile of the ice sheet

When it was built, Camp Century was publicized as a demonstration for affordable military outposts on the ice sheet and a base for scientific research.

The US military only revealed its true purpose after it was abandoned, informing the Danish government – which controlled Greenland – of Project Iceworm’s purpose.

Camp Century was one of the first facilities to be powered by a portable nuclear reactor, which provided electricity and heat.

When the camp was dismantled, the reactor was removed and the hazardous waste was buried. The remaining infrastructure had to be enveloped in layers of ice and snow.

Previously, scientists used conventional radar images to estimate the depth of Camp Century.

This work provides crucial information about when melting and thinning of the ice sheet could re-expose the camp and the remaining biological, chemical and radioactive waste it contains.

However, the new UAVSAR image was captured completely by accident.

“Our goal was to calibrate, validate and understand the capabilities and limitations of UAVSAR for mapping the internal layers of the ice sheet and the ice-bed interface,” Greene said.

“Without detailed knowledge of ice thickness, it is impossible to know how the ice sheets will respond to rapidly warming oceans and atmosphere, greatly limiting our ability to predict the rate of sea level rise,” Gardner added.