The Uranus mystery is SOLVED after 38 years – and it suggests the planet isn’t as strange as we thought

Uranus is often considered the weirdest planet in our solar system.

But a new study suggests the gas giant may not be as strange as we thought.

Researchers from University College London (UCL) say the mysteries surrounding Uranus may be the result of an unusually powerful solar storm that happened to occur at the same time a spacecraft was visiting the planet.

That spacecraft – NASA’s Voyager 2 – flew past Uranus in 1986, providing the first glimpse of the planet up close.

And no spacecraft has been back since.

“Almost everything we know about Uranus is based on the two-day flight of Voyager 2,” said co-author Dr. William Dunn.

‘This new study shows that much of the planet’s bizarre behavior can be explained by the magnitude of the space weather event that occurred during that visit.’

Based on the findings, the researchers are calling for a return mission to Uranus to find out what it’s really like when you’re not in the middle of a solar storm.

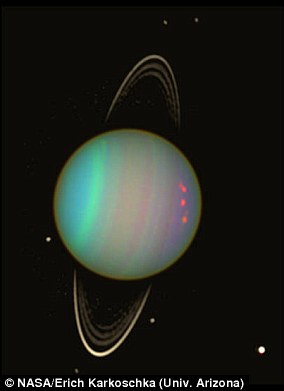

Uranus is often considered the weirdest planet in our solar system. But a new study suggests the gas giant may not be as strange as we thought

Researchers from University College London (UCL) say the mysteries surrounding Uranus may have been the result of an unusually powerful solar storm that happened to occur at the same time a spacecraft was visiting the planet.

In January 1986, NASA’s Voyager 2 became the first and so far only spacecraft to explore Uranus.

The mission captured the first images of Uranus, but also discovered several oddities.

Uranus’ radiation belts turned out to be incredibly intense, while its magnetosphere was nearly empty of plasma.

This meant there was no obvious source of charged particles to fuel these intense bands.

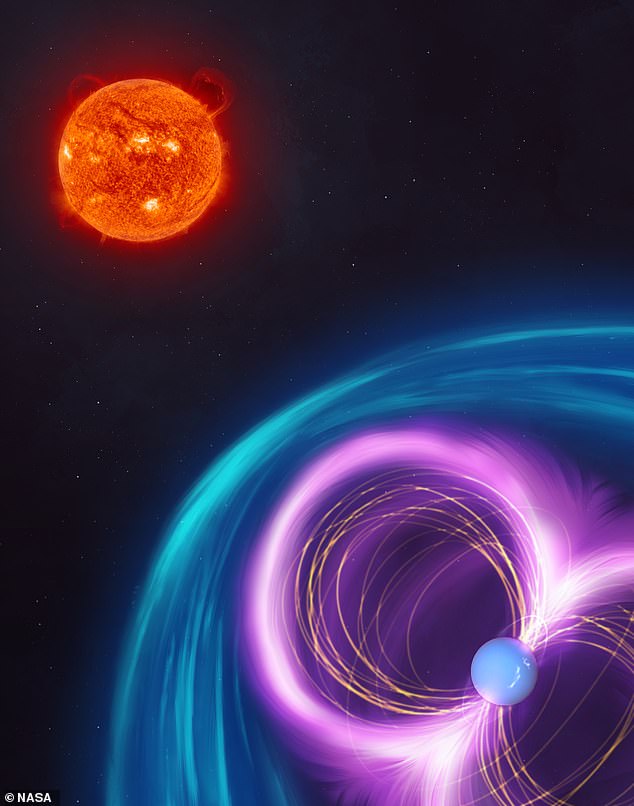

In their new study, the researchers found that a ‘hurricane’ of extreme solar weather could explain this result.

The hurricane likely crushed Uranus’ magnetosphere, pushing plasma out and strengthening the radiation belts by feeding electrons into them.

And Uranus itself wasn’t the only celestial body affected by this event.

Uranus’ five moons were long believed to be dead worlds due to the planet’s nearly empty magnetosphere.

NASA’s Voyager 2 captured the first images of Uranus, but also discovered several oddities. Uranus’ radiation belts turned out to be incredibly intense, while its magnetosphere contained virtually no plasma. This meant there was no obvious source of charged particles to fuel those tires

But the new findings suggest the moons could be geologically active after all – and may even have oceans.

“If Voyager 2 had arrived just a few days earlier, it would have observed a completely different magnetosphere on Uranus,” said Dr. Jamie Jasinski of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), who led the study.

‘The spacecraft saw Uranus in conditions that only occur about 4% of the time.’

Based on the findings, the researchers call for a new – and well-considered – mission to Uranus.

“We now know even less than we thought about what a typical day in the Uranian system might look like and are even more in need of a second spacecraft to truly understand this mysterious, icy world,” said Dr. Dunn.

‘A key piece of evidence against the existence of oceans on the moons of Uranus was the lack of detection of water-related particles around the planet – Voyager 2 found no water ions.

‘But now we can explain that: the solar storm would actually have blown away all that material.

‘The design of the upcoming NASA flagship mission to Uranus should be carefully considered in the context of these findings.

“For example, we want instruments that can detect nudges in the magnetic field of a moon’s salty ocean and instruments that can measure all the particles in the system to test whether we find water or other important material from the moons.”