In an insidious way, the pursuit of the perfect cuisine is killing American workers

Quartz countertops have become a must-have for modern kitchens and bathrooms in wealthy households.

But the workers who make them develop a fatal condition called black lung.

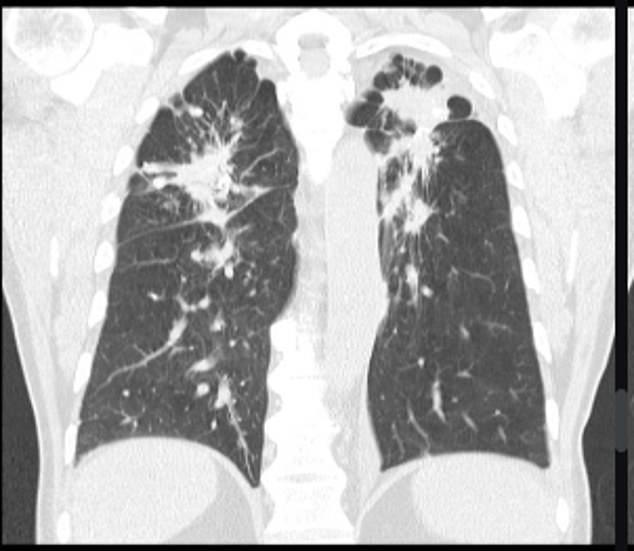

The disease, known medically as silicosis, occurs when small pieces of stone, small enough to penetrate face masks, are inhaled and make micro-cuts in the lungs.

Over time, these tears cause irreversible damage to the organs, making the condition essentially a death sentence unless the person undergoes lung transplants, which only require them to survive for a handful of years.

Now dozens of victims are suing brickmakers for failing to protect them in a growing wave of lawsuits that could upend the world of home renovation.

One of those workers is Gustavo Reyes Gonzalez of California, 34, who underwent a double lung transplant after moving to the U.S. from Mexico and building rich family kitchens and bathrooms throughout Orange County.

He won at least $8 million or possibly more, depending on what a judge decides next month, against companies that make and distribute artificial stone, after the jury agreed that they were at least partially responsible for the disease that left him in pain and almost caused pain. dead.

His lawyer James Nevin told DailyMail.com that he is currently representing about 300 workers in California who have suffered painful lung injuries as a result of their work.

Many of the victims are between thirty and forty years old and will die within about ten years.

Researchers warn that cutting quartz countertops releases silica dust, which can damage people’s lungs (stock)

Gustavo Reyes Gonzalez worked for years in brick factories where he constantly inhaled invisible silica dust. It penetrated his lungs and caused a build-up of scar tissue, permanently damaging his lungs. He has since undergone two transplants

Mr Nevin told DailyMail.com: ‘We find a prevalence rate of 92 per cent – most factory workers will develop silicosis… this is just the tip of the iceberg.’

Mr. Gonzalez is one of dozens of plaintiffs in cases alleging that brickmakers and distributors covered up the risks of working with their products, but he was the first to go to trial.

His lawyers believe his case is a harbinger of more cases to come involving Mr. Nevin add that ‘it is the first of many hundreds, if not thousands.’

Mr. Gonzalez immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico as a teenager to escape poverty, and began cutting slabs of quartz stone from morning to night, six days a week, for use in kitchens and bathrooms.

The durable stone is a popular choice for Americans looking to update their countertops because it is heat and stain resistant and more durable than granite.

For the customer, it is a harmless, aesthetically pleasing addition to the home. But for the worker who saws off pieces and cuts them to size, the stone is deadly.

Although quartz is a naturally occurring mineral, the type found in American homes is a mixture of silica – a chemical compound – and other materials such as metals, resins and dyes.

When workers like Mr. Gonzalez inhale the dust while sawing pieces of it, the particles travel to the lungs and cause inflammation and scarring.

This typically causes permanent damage to the lungs, causing shortness of breath, severe coughing, and eventually oxygen therapy and at least one lung transplant.

Mr. Gonzalez noticed his symptoms worsening in 2020 after working in the industry for more than a decade. It would take about a year to discover the true nature of his diagnosis.

He told it Business from home: ‘(The pulmonologist) told me that I had silicosis. I asked him what that was and he said, ‘You are sick because of your work, because you inhaled silica.’

‘I asked him, ‘What are we going to do? Is there a treatment?’ and he said, ‘We can’t do anything for you because there is no cure for this disease.’

Mr. Gonzalez left his doctor’s appointment in crisis, certain he was going to die.

He added: “I decided to keep working because I needed to save some money for what was to come. Actually, I was saving money for my funeral.”

Mr. Gonzalez testified that he often worked in a dust fog that made his mask dirty. The manufacturers never warned him and his colleagues that working with the artificial stone could cause irreversible health damage

Mr. Gonzalez only survived because he was able to undergo two lung transplants in February 2023.

But hundreds of thousands of Americans are not so lucky. They languish on long waiting lists for transplants, and every day seventeen people die on those waiting lists.

According to one of his lawyers, Raphael Metzger, Gonzalez will need another one in seven to 10 years and is unlikely to live past his 50s.

Mr. Metzger said: ‘Hopefully he has another sixteen years to live, but it won’t be a high-quality life. He’s not doing well. He will never be whole.”

Mr Gonzalez has worked in a series of stonemason’s workshops and emphasizes that the problem faced by workers is common and widespread.

He testified that at times a cloud of dust hung in the air above the workers at these stores like a thick fog.

His mask became “very dirty” and even when he cut the stone with water to minimize exposure to dust, the stone later dried and released “a lot of dust.”

Caesarstone, which manufactured the quartz, said it was up to the shops, not the stone manufacturer, to ensure worker safety. Caesarstone asked them that.”

Much of the multi-week case revolved around determining the protective measures necessary to protect workers from silica dust generated by artificial stone, the Los Angeles Times reported.

A series of expert witnesses have testified about the dangers of cutting through such stone slabs. Dr. Kenneth Rosenman emphasized that Reyes Gonzalez developed silicosis even though he used water dispensers, which Rosenman said were “not sufficiently protective.”

Industrial hygienist Stephen Petty, another plaintiff’s expert, characterized N95 masks as “bottom of the barrel” protection against engineering rock dust. He added that even high-performance respirators with clean air tanks are not a “permanent solution” because workers tend to adjust the fit, disrupting the protective seal.

Mr. Gonzalez’s case and those of dozens of other workers will likely have a profound impact on the home renovation industry, as demand for materials with lower silica content is likely to increase.

Safety protocols for stone manufacturers are also likely to become stricter, requiring more expensive dust control and ventilation systems and more personal protective equipment. Many stores like the one where Mr. Gonzalez worked for more than a decade could face financial losses as they try to meet new standards.

Silicosis appears on a CT scan as small white nodules scattered throughout the lungs. Scan courtesy of radiopaedia.org

A ban on artificial stone is not on the horizon, but the wave of lawsuits could lead to further regulatory action, including stricter exposure limits from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and improved monitoring of air quality in stores and factories.

Gonzalez’s fight is far from over. He now faces a lifetime of daily medication, increasing his risk of cancer due to the immunosuppressants he needs to prevent organ rejection.

His medications have left him infertile, and he and his wife will never be able to fulfill their dream of having a child.

His severe coughing fits also damaged his stomach and diaphragm, requiring additional surgeries. In total, his life expectancy has been extended to just 10 years.

Gonzalez holds stone manufacturers responsible for concealing the dangers of their products: ‘They make the material. They know the content of the material. They know which products are in the material.

“They should have warned us about that, and they didn’t tell us about it.”