I tried to donate my kidney to save a life – then doctors found something that will end mine

A North Carolina man was diagnosed with terminal cancer just before he was cleared to donate one of his kidneys.

At age 50, Jeff Stewart had been trying for more than a decade to donate his organ to someone in need. It wasn’t for a family member or anyone he knew personally, but because “it seemed like the right thing to do.”

After countless tests, fasting and losing 35 kilos, the father of seven was finally approved as a donor in July 2022. But after a routine CT scan before being officially added to the donor register, Mr Stewart was rejected again.

This time it was because scans revealed a tumor that turned out to be stage four adenocarcinoma, a form of stomach cancer that is considered incurable.

The pharmaceutical consultant was shocked at not showing any symptoms and said: ‘It was extremely lucky that they had noticed it.’

TRAGIC: John, pictured with his youngest daughter, had no symptoms before his cancer diagnosis

Yet he was diagnosed with stage four stomach cancer after trying to donate his kidney to a stranger in 2022

Mr. Stewart, now 52, is no stranger to playing the odds. In 1994 he won the Jeopardy! College Championship, taking home more than $25,000. But despite his past luck, he said The patient story: ‘I hope not to be cured.

‘I don’t expect to recover from this. The numbers are what they are, and that’s okay.

“I’m so grateful for the time I’ve had and being able to do things that I hope matter.”

Stomach cancer, which affects nearly 27,000 Americans and kills 10,000 people annually, is most often diagnosed with an upper endoscopy, a procedure in which doctors insert a tube with a camera on the end down the throat and into the stomach.

However, when Mr Stewart underwent an endoscopy as part of the kidney donation protocol a few weeks before diagnosis, his results came back clear.

Adenocarcinoma is a tumor that forms in the glandular tissue that lines organs such as the stomach and releases mucus.

More than nine out of ten stomach cancers are adenocarcinomas.

His doctors believe that this was not visible on the endoscopy because he had undergone gastric bypass surgery more than ten years earlier.

Mr. Stewart, pictured with his wife Jen and all seven children

The gastric bypass surgery, which is performed up to 300,000 times a year in the US, involves dividing the stomach and small intestine and connecting them in a ‘Y’ shape.

This means that food bypasses the stomach and the first part of the small intestine, preventing the digestive system from absorbing all the calories, resulting in weight loss.

In Mr Stewart’s case, ‘there was nothing to see’ because the tumor was in the part of the stomach that was no longer functioning.

He said: ‘[The tumor] was in the bypassed part of my stomach. I wouldn’t have any symptoms. Even if it had gotten really bad, it wouldn’t have become food, there wouldn’t have been a blockage there until it had really gone much further beyond my stomach.”

It was confirmed that the cancer was caused by a mutation in Mr Stewart’s FGFR2 gene.

Normally, this gene helps make proteins responsible for cell division, blood vessel formation, wound healing and bone development.

However, a mutation can cause the protein to become overactive, which can lead to the development of cancer cells. Experts estimate that this mutation is responsible for as many as one in ten stomach cancers.

In localized cases, stomach cancer has a five-year survival rate as high as 75 percent, but that drops to just seven percent in stage four.

Doctors also found a tumor on one of Mr Stewart’s kidneys, a separate form of cancer called renal cell carcinoma, which is not linked to stomach cancer.

It is unclear whether it was the kidney he intended to donate or at what stage it was discovered.

Mr Stewart quickly underwent surgery to remove both tumours, with doctors discovering that the stomach cancer had spread deep into his stomach lining. Within weeks, he began several courses of chemotherapy, followed by radiation.

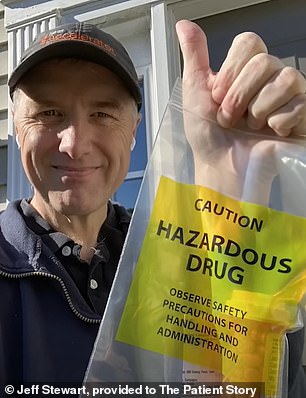

He said, “I haven’t had the type of chemotherapy that makes your hair fall out, but I have had the type that destroys your nerves.”

Mr. Stewart is no stranger to playing the odds. In 1994 he won the Jeopardy! College Championship (pictured here), taking home $25,000 and a new car

He has undergone several rounds of chemotherapy and radiation, but the treatments are mainly intended to slow the cancer rather than cure it. Both treatments had numerous side effects

The drugs, specifically a chemotherapy drug called oxaliplatin, sent shock waves through his body every time he picked up something cold, such as an ice pack.

“I felt like I was getting a bag,” he said.

After the first treatment, Mr. Stewart experienced a burning sensation on his arm, as if it were on fire, but at the same time it felt cool.

He said, “I’ve never felt anything like it before, and it stayed that way for days.”

Radiation also brought side effects, including extreme fatigue.

“Your light is getting dimmer because all you want to do is sleep,” he said.

For Mr. Stewart, chemo and radiation are not intended to cure his cancer, but to help slow the disease and make him more comfortable. Even if doctors decide to offer him more experimental treatments, he estimates they may only give him a few extra months.

He said: ‘[Treatment] must kill every cancer cell, and if it doesn’t, I die. And that didn’t happen, for me. I’m not depressed, but the years have worn me down. It’s harder.

‘It makes very simple things more important. It can be invigorating. There’s a certain joy in knowing you have such a big canvas and not ‘I don’t know how big’. I can fill that canvas. I can make something of that.’

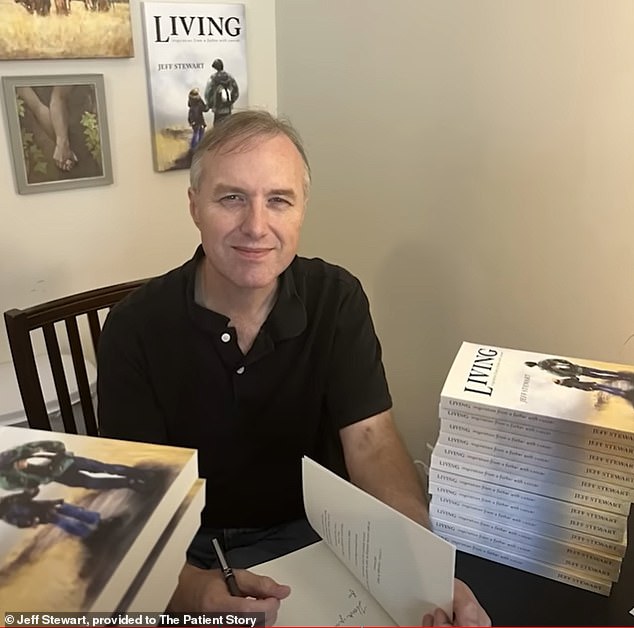

As part of his coping process, Mr. Stewart wrote a memoir (pictured here) for his children with all his best advice ‘so they would get it when I was gone’

As part of his coping strategy, Mr. Stewart wrote a memoir, Life: inspiration from a father with cancerto “put all my best advice in there for my kids so they can get it when I’m gone.”

The book contains messages such as recognizing luck and happiness and trying not to focus on things you have no control over. The goal is to help his children and his wife of more than 30 years, Jen, cope with his death in the long term.

He said: ‘I have seven children. I hope that the pain of my death, when it comes, will not be too devastating for them and for my wife and my parents or my sisters.

‘I hope so in those parts. But I don’t hope for a cure, because there is nothing in the pipeline.’

Of all the advice in the book, Mr. Stewart noted that the best is about kindness.

He said, “Kindness is all that matters. It’s fun to be smart, it’s fun to be rich, it’s fun to be strong, it’s fun to be brave.

“But if we’re not nice, nothing else matters.”